In the run-up to the launch of the new GDPR privacy protections, most of the focus has been on how it will affect huge data-mining tech giants like Google and Facebook. But as many people are finding out today, GDPR applies to any site that collects user data or, in the case of publishers like Gizmodo Media Group, displays advertisements that collect this data. What that really means in practice is extremely complicated.

GDPR – formally known as the General Data Protection Regulation – has been years in the making, and for all intents and purposes, it was designed to tame the abuse of user data by large monopolistic networks and give users more control over their personal information. But the fact is, the bulk of the internet economy runs on data these days, and even small websites just plug-in larger ad networks for revenue. Does GDPR apply to your favourite web forum for Cabbage Patch kids enthusiasts? Most likely. A recent survey from the Ponemon Institute found that half of the companies polled said the wouldn’t be ready for the deadline, and we’re already seeing some major news sites simply block Europe while they catch up.

Michael Priem is CEO of digital marketing firm Modern Impact, and he’s advised companies like Samsung and Hewlett-Packard ahead of the GDPR launch. As he told us, “for pretty much every publisher, the economic currency of the internet and our digital lives is advertisements.” That sounds obvious, but the way those ads are delivered is a lot more complex than it used to be – which means ensuring that they comply with GDPR is a total mess.

Recently, you’ve probably been bombarded by pop-ups, notifications, and emails that are informing you about changes to a site or service’s user agreement. “Being compliant with GDPR requires that you have the disclosure requirements, that you give consumers the ability to opt out, to request their personally identifiable data not be stored, and that you speak in plain language around what they are opting into with data collection,” Priem told us. But GDPR is a sprawling piece of legislation that involved the European Union’s 28 member states navigating each of their regional priorities and sifting through 4,000 amendment proposals. Those that confused users with gigantic terms of service written in opaque legalese now have the tables turned and must try to figure out what the law is actually saying.

Facebook collects your data when you use its platform, and it collects your data even if you don’t use its platform. It follows users around the web with its cookies, and it builds shadow profiles of non-users in case you sign up one day. It processes that data, makes inferences about it, collates it with your friends’ data, and until recently, it even bought data about users from third parties. The amount of information it knows about users is only rivaled by Google, and the two companies together control almost 60 per cent of all digital advertising.

But smaller media companies utilise advertising services that collect data as well. A huge international publisher like the New York Times has its own complex advertising operations that are coupled with the web of third-party advertising networks that target ads based on your browsing behaviour. The web also made it easy for anyone to be a publisher, and according to Priem, even if you set up a personal website a few years ago, plugged in Google AdSense and forgot about it, you still might have legal exposure under GDPR.

There are a lot of different ad types on the web, and in most cases, the publisher itself is doing little to no personal data collection. But they do pass along data to advertising networks like Google’s Double Click service, which utilises cookies and IP addresses to target ads based on your history and the content of the site your visiting. A lot of smaller publications, like Gizmodo, use what’s known as a demand-side platform to manage real-time bidding from multiple ad networks. User data is passed along from the publisher to the networks, it’s evaluated to determine a set of interests, and an ad is served by the highest bidder. Known as programmatic ad buys, this system is standard across the industry, and even though a publisher may not be collecting anything more than incidental data, they could still be on the hook for GDPR compliance along with the ad network that’s actually collecting the data.

The idea of giving users a chance to request their data not be stored seems simple enough, but most smaller companies aren’t equipped to deal with a sudden deluge of data requests. Because of the haphazard manner in which data privacy has been treated over the last couple of decades, some organisations might not even know what data they have on hand, or what server is storing it.

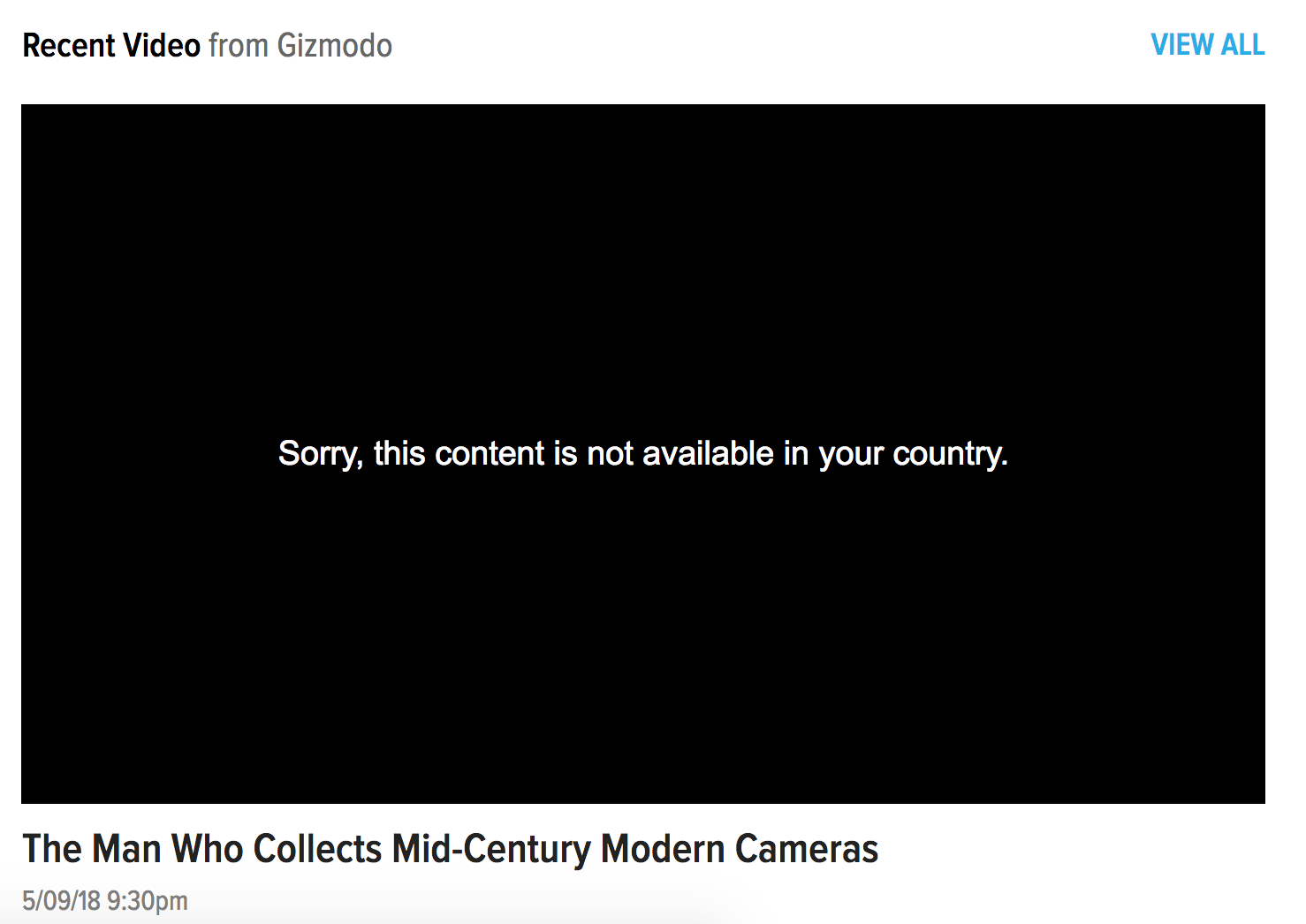

For smaller sites, easier automated solutions for compliance are popping up. Some sites are electing to only run non-targeted ads in the EU, and publishers like NPR are offering a plain text version of their site to those who don’t agree to their terms of service. At Gizmodo, we’ve temporarily blocked all ads for visitors accessing the site from Europe. And we geo-blocked all videos for the EU market as well to prevent showing ads that run at the beginning of our videos. This is just a stopgap as we work toward a more elegant solution, like utilising the new GDPR-compliant IAB framework.

This is what it looks like if you try to watch a video ad on Gizmodo from the EU now.Screenshot: Gizmodo

Even though we’re seeing the owners of huge publications like the Los Angeles Times and the New York Daily News simply block European users on Friday morning, that may not even count as a short-term fix. GDPR applies to all European citizens, not just the ones currently located in Europe. Theoretically, a website serving someone from France who’s currently located in Tokyo could be in violation of the regulations if everything isn’t in place. “And the fines that regulators intend to impose are clearly defined and they’re not small, they’re powerful,” Priem emphasised to us. He’s right that the regulations clearly give authorities the power to levy a fine of up to 4 per cent of a company’s global revenue for violating GDPR, but no one knows how much of that power will be regularly exercised.

A lot will come down to what services users actually follow through on reporting sites for being out of compliance, and regulators’ ability to process the cases. Earlier this month, Reuters surveyed EU authorities on their preparations; 17 of the 24 offices that responded said they didn’t have the funding or the power to enforce GDPR’s requirements.

The fact is, this is only the beginning of a total realignment of the web’s approach to privacy. The EU is very much getting what it set out to do while everyone scrambles to get themselves in compliance, and the biggest offenders are likely to be the ones who are made an example of. On the day GDPR went into effect, Facebook and Google were hit with their first formal complaints for allegedly violating the law. The complainant claims that the two companies are still requiring consent for data options that aren’t strictly necessary for the service. This is likely to snowball into arguments over what is and isn’t “necessary,” like Facebook’s ongoing claim that tracking non-users is essential for security purposes. The good news is that regulators will likely get a better understanding of what is necessary for this industry and mega-rich companies will be paying to build the case law.

A lot will depend on the public understanding that the destinations its visits depend on ad revenue to survive. The argument that small businesses and startups will be hit hardest by regulations isn’t completely without merit, but this is a process of building a balance. If we find down the road that companies like Facebook managed to become so big in the previous era of non-privacy that the barrier for entry is too high for anyone to compete, that’s just all the more reason to break up the giants and start again.