Going into Star Trek: Discovery, fans were told to expect something new. It would be dark. It would be modern. It would push the boundaries of where Star Trek had boldly gone before. Now that we’re at the end of Discovery‘s first season, we know it did take a few steps in those directions – but every time it did, it retreated back the minute things got too uncomfortable.

Although we know from a production standpoint – and more specifically, a writing standpoint – Discovery‘s maiden season was created as one continuous piece, it’s hard to not look back at the season and see it divided into two distinct halves. Part of that is simply because of the way the show was delivered, doled out in two “chapters”, but it’s also thematic. The first “half” of Star Trek: Discovery was all about the hard choices made by its characters, as well as the institution our heroes belonged to. Its second half, meanwhile, was mostly dedicated to turning tail from those hard choices, handwaving away their most interesting consequences with the fannish nostalgia of one of Star Trek‘s oldest conceits: The Mirror Universe.

The first half of Discovery‘s first season was as full of promise as it was about some truly damaged people. As the scene was set for an examination of how to reconcile the two wildly different halves of Starfleet – one half, a peaceful scientific research organisation; the other, a militaristic fleet of soldiers – in a time of conflict, we were introduced to characters who had way more problems than any Star Trek crew we’ve ever seen before.

There’s Michael Burnham, an officer stripped of her rank for making an awful error in judgment that flung the Federation into a bloody war. There’s Captain Lorca, a war hawk who bristled with Starfleet’s scientific ambitions and saw military might as what would ensure the Federation’s survival. Paul Stamets, a scientist tossed into a conflict he never wanted to face, is forced to tinker with technology he barely begins to understand, breaking Federation law and seemingly losing his mind – and eventually his partner – in the process. Ash Tyler, a man deeply haunted by horrific torture endured as a prisoner of war, is given not just a phaser, but security command over the Federation’s prized secret warship, pointed right in the direction of his abusers. Even characters like Saru and Tilly, who mostly escaped the darkest corners of Discovery‘s tone unscathed, found themselves wrenched out of their expected Starfleet careers and put into the cold, and often unforgiving, reality of war.

These characters weren’t just fascinating to explore on a personal level – something the show struggled to do as it grappled with a condensed season and some lightning pacing – but because of what they ultimately said about the state of the Starfleet of the 2250s we were introduced to in Discovery. How desperate was the Federation, blindswiped by a brutal war with the Klingons, that these people were allowed to operate they way they operated, not just as members of Starfleet, but on the fleet’s most powerful starship? How could this organisation – one seemingly so neglectful of the ideals fans had known it to hold over half a century of Star Trek shows – reconcile itself with the Starfleet we knew of in the time of Kirk and Spock, just a decade after the events of Discovery? How could Starfleet evolve beyond this immediate existential crisis, when it’s an organisation that messily blurs the lines between a military construct and a beacon of science and peaceful exploration? Although the show struggled to get this across at times, when it did there were hints of the fascinating potential Discovery had, even if there were still grumbles about how it all fit into the wider Star Trek mythos.

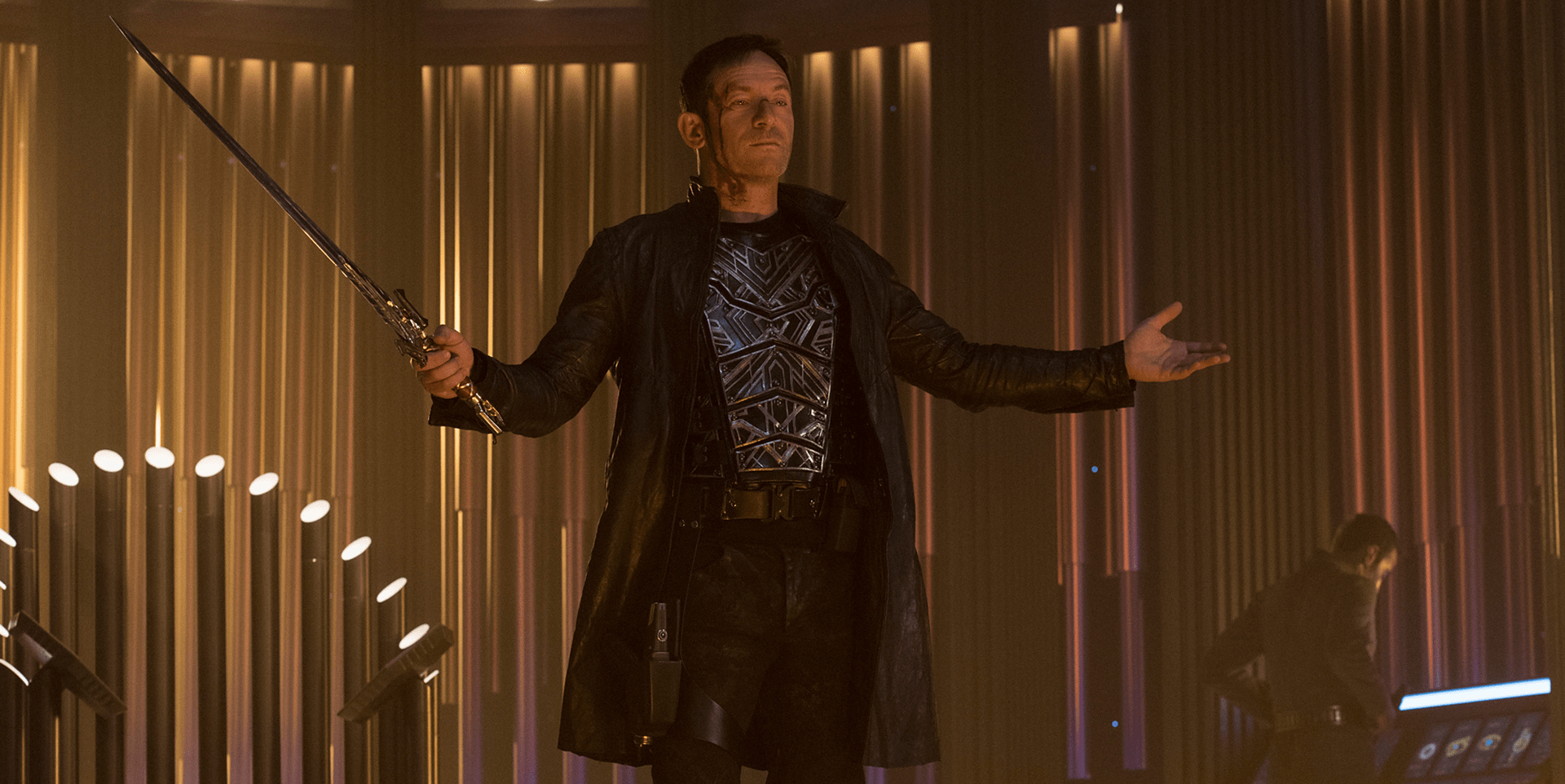

But then the show’s back-half provided an easy way out from all that fascinating potential, thanks to the introduction of the Mirror Universe. Was Stamets slowly being driven mad by a Federation pushing his dangerous scientific research too far? No, he was just getting visions of the Mirror Universe adventures to come. Was Lorca a dangerous, morally grey maverick in Starfleet that reflected an unpleasant aspect the of the organisation most people chose to ignore? No, he was a comically evil Mirror sleeper agent looking for a way to get back home and – literally, he says this – “Make the Empire Glorious Again.” Even when Admiral Cornwell is set to betray Starfleet’s ideals going into the final episode by starting a mission to literally blow up the Klingon homeworld from the inside, she uses the Mirror version of Phillipa Georgiou, the horrifyingly cruel ruler of the Terran Empire, as her avatar. Because if you want your audience to explicitly know that a plan is bad and evil, make sure it’s enacted by someone who regularly walks around executing people on a whim and eating sentient aliens for dinner, just to get the point across in case they missed it the first time.

And when the show couldn’t find a Mirror Universe answer to the Prime Universe problem of Ash – or rather the Klingon Voq in disguise as Ash, as the long-predicted reveal turned out to be – it simply shrugged the story away. In what was basically an aside to the Mirror shenanigans swirling all around the second half of the show, Ash rapidly converted back to being himself, but with the memories of Voq still residing within, and everything was somehow ok. And then by the end of the season finale, Ash left with Voq’s commander L’Rell, to sweep the inconvenience of having a Human-Klingon hybrid hanging around Starfleet under the interstellar rug.

All that remains is Michael, who took the biggest journey but even then, her hardest challenge this season – having to overcome the awful decision she made in the season premiere, at the cost of her commission, her future, and her beloved mentor – got a Mirror Universe solution. Her decision to save the Mirror version of her beloved captain Georgiou from death in the Mirror Universe has ramifications that spiral wildly out of Michael’s control, not least because Emperor Georgiou is evil as hell. But unlike the events surrounding Prime Georgiou’s death, which saw Michael have to live and attempt to overcome an overwhelmingly grave consequence, Mirror Georgiou gave Michael something to fight directly, and literally confront – and let escape! – to earn her redemption in the eyes of the Federation. Sure, she started a bloodbath of a war with the Klingons that cost the lives of hundreds upon thousands of people, but hey! She stopped Admiral Cornwell from making a terrible mistake with help from a universe of alternate space fascists, and that’s ok as long as we forget the first bit, right?

The Mirror Universe will define Star Trek: Discovery‘s first season far more keenly than anything like Burnham’s mutineer status, or the continuity-boggling spore drive ever will. It offered both easy fan cred when the show needed it the most – at the cost of introducing an almost impenetrable layer of continuity for new viewers – and the easiest way out of the tough questions the series had asked of itself in its first half.

There’s long been a comparison among Trek fans bettween what Discovery has tried to do with examining the ideals of a peaceful utopia in wartime and what Deep Space Nine did with that idea 25 years ago. On a surface level, they’re very similar premises: An overwhelming warrior race (Discovery‘s Klingons, DS9‘s Dominion) puts the Federation on the retreat, and to find any way of avoiding complete and total annihilation, the Federation is forced to wrestle with the idea that it may have to sacrifice some of its most sacred ideals in the process. But where DS9 took that conflict and made it personal, introspective, and most importantly consequential for its characters and institutions, Discovery deflected any self-examination it tried to attempt, and instead found itself a whole universe of evil doppelgangers to act as scapegoats.

“In the Pale Moonlight,” one of Deep Space Nine‘s most powerful and beloved episodes – hell, one of the greatest episodes of Star Trek, full stop – sees Benjamin Sisko forced to live with having committed truly terrible acts to give the Federation a chance to win its war with the Dominion. The show would only rarely revisit the turmoil those acts inflicted on Sisko, but they were never gone or forgotten. Audiences knew, even if most of the characters of Deep Space Nine didn’t, that their hero had sacrificed part of Star Trek‘s very soul to save the Federation from certain doom. Benjamin Sisko had to live with the consequences of his actions – and, chillingly, was ok with doing so – even if they ultimately lead to peace.

By the end of Discovery‘s first season, no one of any particular importance has had to do the same. Everything that challenged the Federation in its darkest hours in Discovery can be blamed on Mirror Lorca, on Mirror Georgiou – who gets to run away with her freedom – or on the very existence of the Mirror Universe itself. Anyone but Starfleet and the crew of the Discovery.

When Starfleet gathers at the climax of the finale so Michael can give a big speech about the Federation’s ideals, she mentions that there are no shortcuts on the road to righteousness. But in Discovery, we’ve had nothing but shortcuts – promising scenarios that would ask challenging moral questions of our heroes, copped out by finding something more obviously sinister to pin them on instead. And that doesn’t just apply to character progression for the series’ stars, but even whole narrative devices. The spore drive, Discovery‘s wildly powerful technology that’s suspiciously absent for the rest of Star Trek history? Stamets gives a single line in passing near the end of the finale to say that they can’t use it any more, because Starfleet wants to find a non-human pilot. The brutal conflict with the Klingons that’s rolled on for months and months? Ended in moments by giving a religious dissident a planet-killing bomb to bend her fellow Klingons to her will. The fact that Admiral Cornwell was going to use an alternate-reality dictator as a proxy to enact genocide? Not picked up on in the slightest, and perhaps will never be mentioned again.

For all the glitz and glamor of its lavish production values, its excellent cast, and its swanky cinematography, underneath the sheen there wasn’t anything particularly new that Discovery had to say about Star Trek or its universe. The Federation, even in war, emerged with its ethos firmly, unquestionably intact… because the people who dared to question them were revealed to be unquestionably, unspeakably evil in the grand scheme of things. Starfleet’s mission is still pure, and now we get to explore it further with a crew of characters who are finally, slowly but surely, pulling together into a team as loveable any past bridge crew, even if it’s taken some questionable narrative hurdles to get there.

But despite the disappointment that in its most contemplative of moments Discovery was all bark and no bite, there is definitely hope for the voyages of the U.S.S. Discovery as we sail into season two. If the show can focus itself back in on its cast of heroes instead of going out of its way to please continuity snobs and relying on shocking twists, there’s a ton of potential, albeit one that requires a lot of the forgiving and forgetting Burnham went through in the finale.

Admittedly, this wouldn’t be the “new” take Discovery desperately wanted to try to be, but it’s also what Star Trek does at its best. It’s a well-trod path, but one Discovery should be proud to follow.

Besides, you never know who you might encounter along the way.