NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Peggy is something along the edge of Saturn’s ring, a glitch whose source we’ve never seen. Cassini took a last peek at Peggy during its Grand Finale destructive plunge, adding a final piece to the puzzle for future researchers to pour over when trying to understand this mysterious disturbance.

27-year Cassini project veteran Carl Murray of Queen Mary University of London recalls his first sighting of the ring glitch, in early 2013. He was pouring over an image of Saturn’s moon Prometheus at the outside edge of the A-ring, deliberately exposed to show the background stars. “We saw this kind of bump-glob-feature-object whatever,” he told me last week, during the lunch break of the Cassini final Imaging Team meeting, as we chatted at the Huntington Botanical Gardens near Caltech.

“We obviously wanted to know, ‘Was it real?’” said Murray. He and his team quickly checked previous images of the area, and now that they knew what they were looking for, they kept finding that strange, stepped-out glitch in the otherwise smoothly-curving edge of the A-ring. “The day I found it was my mother-in-law’s birthday,” Murray recalled, so he named it Peggy in her honour. “It seemed appropriate.”

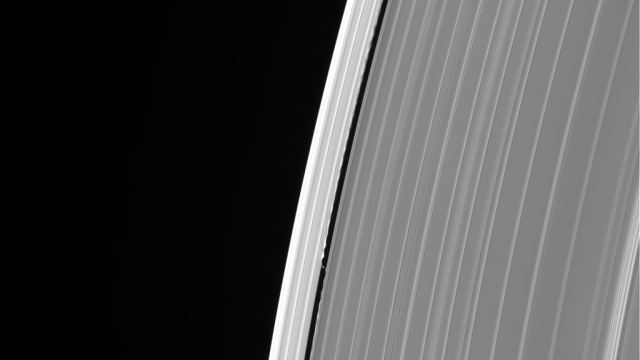

A 1,207km long bright feature along the edge of Saturn’s A-Ring as seen on April 15, 2013. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

Soon, the team’s questions about Peggy expanded: “What is it? Where did it come from? Where is it going?” he explained. “We’ve been tracking it almost ever since.”

Murray and his colleagues realised the glitch must be caused by an object embedded in the rings. “We’ve never actually resolved the object,” Murray said. “All we can do is track the glitch.”

Measuring the size of the disturbance, he quickly realised it couldn’t possibly be a solid moon. “It would be a massive Titan-size moon,” Murray explained. “If a moon that size was there, it would be totally disrupting the ring.” Instead, he figured it must be a dense cloud of dust and debris, possibly encompassing a proto-moon that hasn’t yet broken free as an independent object.

As the mysterious object drifts closer to and farther from Saturn within the rings, it causes the glitch along the outer edge to change speeds. “By measuring the speed of the glitch, we can measure the orbital parameters of the object,” Murray explained.

Including Peggy in Cassini’s final six images of the Saturn system was partly sentimental, but the spacecraft was also collecting valuable scientific information. “Every image we get which should contain Peggy is yet another data point that will help us understand what it is, where it is, where it’s come from, and where it’s going to go even when we’re not around to take images any more,” Murray said. “The fact that it’s one of the last images from Cassini is touching, but we’re doing it for science.”

But tracking an object when you don’t know what exactly that object is can be tricky. Cassini’s imaging team has found Peggy time and time again, but not always where and when they expected it. “Sometimes you see it, sometimes you don’t,” Murray said with a sigh.

This uncertainty made planning the final image tricky. “We actually gave Peggy a large margin of error because it’s a bit wayward sometimes.” Adding to the complexity of the shot, Cassini was on the far side of the system, shooting the rings from across the planet. This means the resolution was lower: at 5km per pixel, Peggy’s characteristic glitch will only be a few hundred pixels in the image.

Murray and his team stayed up late Thursday night waiting for the raw images to download. They brought everything they needed to analyse Peggy right away, working off nervous energy before joining others in standing vigil for Cassini’s final moments.

When I checked in with him via email on Friday, Murray was optimistic but uncertain Cassini had successfully found Peggy one final time, writing, “I would like to think that it is [in] the one that also contains Daphnis,” a tiny moon of Saturn that lies within the Keeler Gap of Saturn’s A-ring, he said, before linking me to the raw image.

Kevin Gill stayed up late on Thursday processing Cassini’s final images for release on Friday morning. “I couldn’t find Peggy in the data though I’m still looking,” he told me, confirming the glitch is being characteristically difficult to identify. “Peggy’s probably there, I just haven’t found exactly where yet.”

“I’m used to every day going to the computers when the images come down [to] just look for fun stuff, like Peggy!” explained Murray. “It’s going to take me a while to get used not getting to see these images every day.”

Cassini’s mission is done, and its raw image gallery will never have a new update. But Murray, his postdoc, and the rest of the mission scientists still have fruitful years ahead of them pouring over thirteen years of data and trying to understand this beautiful, complex Saturnian system. Perhaps, they will even come to understand Peggy a little bit better.