As global temperatures rise, many animal species are edging toward the poles and even climbing mountains to stay within their preferred temperature ranges. The result is a slow but noticeable shift in the world’s ecosystems, both on land and at sea.

Under the Sea

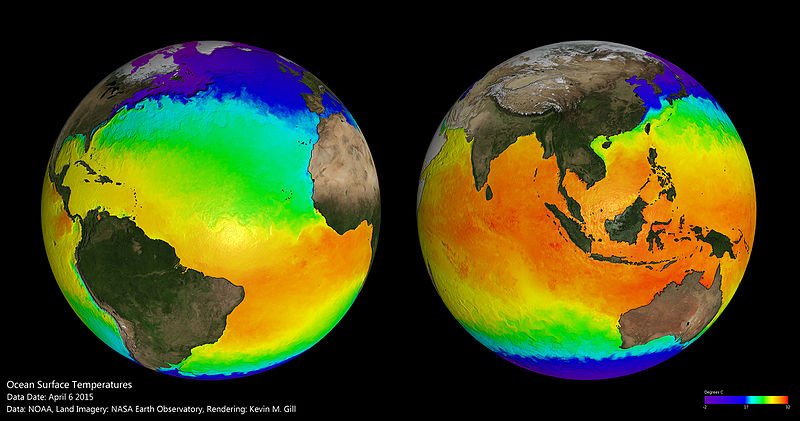

Ocean surface temperatures on 6 April 2015. Image: NOAA.

The mass shift toward the poles is especially noticeable in the ocean, where organisms can disperse over much greater distances than on land. Marine species have shifted poleward about 72km per decade since the late 20th century, according to a 2013 analysis of 208 published studies of marine species ranges. The studies included a combined 1735 observations of 857 species.

“Over 80% of the nearly 2,000 observations show a pattern that’s consistent with a warming world,” said co-author and marine biologist Pippa Moore of Aberystwyth University in Wales.

Take phytoplankton, the microscopic plant life that forms the base of the ocean food web, as an example. Since the late 20th century, the range of several phytoplankton species has shifted toward the poles by about 470km per decade, as warming opens up higher latitudes as a comfortable habitat.

Phytoplankton. Image: NOAA

Phytoplankton aren’t swimming those vast distances to more comfortable waters; they drift at the mercy of ocean currents. But as the ocean warms up, waters at high latitudes that were once too cold for phytoplankton are now perfectly habitable, so the tiny plants can thrive there. The “leading edge” of their range expands toward the poles. Meanwhile, the “trailing edge” of their range, in warmer waters, contracts more slowly.

That’s because organisms aren’t vacating warmer waters all at once, and the rising temperatures aren’t instantly lethal. Instead, the effect of rising ocean temperatures is what Moore refers to as sublethal: species may not be able to reproduce as well, and fewer individuals may survive, but the species can hang on for a while.

“They might not be growing as much, they might have poorer conditions, but they will still be able to persist. And so you still keep that range edge, but they’re just not doing as well,” she said. “So that’s probably the reason the trailing range edge isn’t shifting as fast as the leading range edge: because you see populations suffering sublethal effects first, before you have sort of localised extinction.”

Staghorn coral forest. Image: Nick Hobgood via Wikimedia Commons

A similar process is happening to some coral species. Coral reefs can’t pack up and move, but in areas where currents carry coral larvae toward the poles, some corals are settling and forming new reefs at higher and higher latitudes. Off the coast of Japan, where sea surface temperatures have increased by between 0.7C and 2.4C since the 1930s, four species of coral have expanded northward at a whopping 14km per year.

Staghorn corals, a familiar sight in tropical Caribbean and Pacific reefs, have also been moving steadily northward along the coast of Florida and into the Atlantic, but they may run into an insurmountable barrier. Coral need sunlight to survive, but higher latitudes receive less direct sunlight than the tropics, especially during the winter months. Staghorn coral that colonise northern waters may have to stick to the shallows in order to catch enough sunlight filtering down through the water.

As coral and phytoplankton move poleward, they’re disrupting entire ocean ecosystems. Coral reefs provide shelter for thousands of species, many of which may be less well-equipped to expand out of the tropics. Nearly everything in the ocean either eats phytoplankton, or eats something else that does, and their poleward shift could create a problem for other species that time their migration and breeding cycles around the availability of tasty phytoplankton to graze on.

Atlantic cod. Image: Peter via Flickr

Larger sea life, further up the food chain, is on the move, too. Bony fish, on average, move about 278km per decade, which has obvious implications for commercial fisheries. Some squid have migrated as much as 200km per year to cooler waters.

Life Ashore

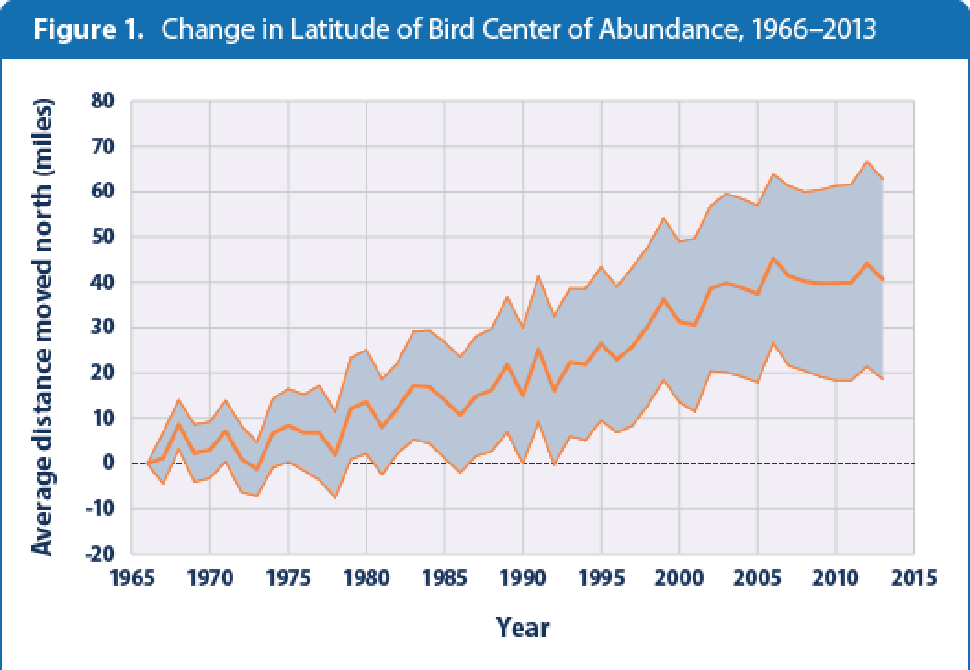

Things move a little slower on land, where animal species’ natural ranges have shifted, on average, about 6km per decade since the late 20th century. Birds have moved the most, primarily because — like the most mobile ocean species — they can cover greater distances.

Image: EPA.

The US Audobon Society has tracked North American birds’ winter ranges and populations every year since 1965. They found that 186 bird species have shifted their winter ranges northward by over 64km in the last 40 years, and 48 of those species had shifted their ranges by over 322km.

Seeking Higher Ground

Birds are also seeking higher ground as average temperatures rise, especially in the tropics. Deep in the mountains of New Guinea, tropical birds like the crested berrypecker have shifted their usual ranges upward by 122 or 152m over the last 50 years, to escape a 0.4C increase in average temperature in their old habitat. And birds aren’t the only ones moving to higher, cooler altitudes.

Alpine pika. Image: Hedgenious via Wikimedia Commons

The round ball of fluff in the picture above is called a pika, or rock rabbit. Pikas live on rocky mountainsides, where they forage for grasses, leaves, and moss. They prefer cooler climates, and have moved uphill about 146m every decade since the late 20th century. That make not sound like much, but on a mountainside, moving up or down a few hundred metres can put you in a completely different ecosystem, with new predators and, often, fewer or unfamiliar food sources. That’s why pikas have gone locally extinct in at least five areas of the US in the last ten years.

And they’re not alone. In Yosemite National Park, average temperatures have risen by about 3C over the last hundred years, and in response, many species have moved uphill. Average temperature drops about 6C per 1km of altitude in the park’s mountains, so zoologists were unsurprised that half of the 28 species they surveyed in 2008 had moved uphill an average of 0.5km since the early 1900s. The alpine chipmunk, for instance, has moved uphill about 610m in the last century, from its old habitat below 2377m to a new range above 2987m.

As they move uphill, species like the crested berrypecker and the alpine chipmunk will find themselves sharing territory with species that didn’t move, many of which will be new competitors for food. It’s a complete reshuffling of the established ecosystem, and it could create a challenge for upwardly mobile species and sedentary ones alike.

Crested berrypecker. Image: markaharper1 via Flickr

But in the long run, fleeing uphill only leaves most species cornered as temperatures rise around them. In New Guinea, the crested berrypecker and three other species of birds have already moved to the 2438m summit of Mount Karimui. Soon, they will have nowhere else to go. Another 1C temperature increase would push the cornered birds into local extinction — and that’s just a fraction of the 2.5C increase New Guinea is likely to see by the end of the century.

“The predicted change by the year 2100 will not only finish off four species on these mountains, but another 10 to 15 species will be put in very precarious positions,” said Cornell University ornithologist Benjamin Freeman in a 2014 press statement.

Moving Toward the Future

Bleached corals. Image: Bruno de Giusti via Wikimedia Commons

But species can’t run away from climate change forever. At the moment, most are expanding into new territory faster than they’re withdrawing from old territory, and that means wider ranges for most shifting species, with a few exceptions. If we can limit warming to 2C above pre-Industrial levels, that may not change.

The result, says Moore, will be increased heterogeneity; ocean neighbourhoods will look much more similar across much larger distances than they do today. But the alternative, if we miss the 2C goal, is much worse: “You see real loss of biodiversity in the tropics, and of course, in the tropics, there’s nothing to replace these climate migrants, because there’s nowhere else warmer,” she said. “If we hit that 2⁰ C target, then potentially it’s not awful. But certainly if we go beyond that 2⁰ C target, there could be quite significant implications for biodiversity, especially in the tropics.”

Top image: Ian Sharp via Geograph.org.uk