Google’s parent company Alphabet has just hired Thomas Insel, the former head of the US National Institute of Mental Health, who has some pretty weird ideas about what his new job will entail.

Insel told a crowd at Chicago Ideas Week that he still isn’t sure what Alphabet wants him to do. But then he explained what he’d like to be doing, which is using Google’s data-mining tools to research mental health at time when suicides in the US are on the rise.

Insel told Fusion’s Casey Tolan:

We’re not seeing any reduction in mortality in terms of suicide because we’re not giving people the care that they need. We would never allow this to happen for cancer, for heart disease, for diabetes.

So how would we reduce suicides, using technology? Insel says that he’d like to develop a wearable sensor to measure mood, cognition and anxiety. This device would track “sleep, movement” and even “language use” for red flags that could indicate mental health problems. Basically, he suggests, it would be a kind of FitBit for your moods and sanity levels.

But there are a lot of problems with this idea. Unlike a fitness tracker, which keeps tabs your physical activity and heart rate, Insel’s mood tracker would try to correlate your physical state with a possible mental state. And that’s where things get dicey, because not everyone experiences stress in the same way. For example, I recently bought the Spire, a wearable that does some of the mood tracking that Insel suggests his device would: it monitors heart rate and breathing, and then tells you whether you’re “focused” or “anxious” or “active.”

But the Spire didn’t accurately read my moods, despite its accurate readings of my physical state. At one point while wearing the Spire, I had to do something that made me anxious. Despite my stress, the Spire claimed I was “focused” — most likely because I was forcing myself to concentrate and breathe slowly. My mental state did not match my physical one.

And that’s a relatively benign example. If we’re going to be judging people’s mental health based on things like heart rate, sleep patterns, breathing, and word choices, there are all kinds of confounding factors that might make a person seem stressed when they are just excited, or feeling awkward or jetlagged. And vice versa. None of this would be a big deal, however, if it weren’t for the fact that Insel wants to use these wearables to intervene in people’s mental health.

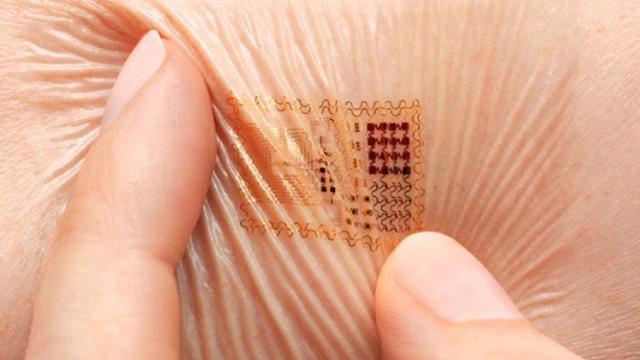

It’s easy to see why Insel would want to use Google’s infrastructure to do this. Suicide rates are up in the US, and studies show that early intervention can save lives. Often people who are depressed will withdraw from the world, isolating themselves from help until it’s too late. In that situation, a tracker that could alert health authorities when somebody is depressed might help. Just wear your device — or something more futuristic, like a skin circuit — save your data to the cloud, and any aberrant readings will be analysed and sent to a mental health professional.

Except, of course, you’re now sharing a lot of hard-to-interpret health data with … whom? Your company’s psychologist? Your local health department? A doctor chosen from your insurance network? Then there’s the question of what healthcare workers will do when they believe you’re not in an optimal mental state. One can easily imagine a message popping up on some poor desk jockey’s monitor: “You’re not in the right mood today. Please take a day of unpaid leave.” Or, worse: “We’ve detected signs of mental instability, based on how you’ve been talking and sleeping. Please report to a doctor immediately.”

This is all made so much worse when you consider the kinds of specious correlations that Insel has already worked on in his previous job as a research neuroscientist at Emory University. There, he tried to show a correlation between genes, hormones, and a predilection for infidelity. I shouldn’t need to spell out how many problems there are with trying to find a physiological measure for something like “fidelity,” which is an idea that comes from culture in humans, and is interpreted in wildly different ways across social groups.

The fact is, we don’t have a technology that can accurately measure emotional turmoil. We have tech that can offer hints, certainly. There are predictable patterns to mental illness, but they aren’t universal. The idea of a mental health monitor whose data is being analysed by algorithms should make us wary.

Insel wants to prevent people from suffering when they experience mental illness, which is a worthy goal. But his ideas about how to do it may cause more harm than good.

Image of skin circuit by John Rogers.