When we think of early logos, we think of 19th and 20th century classics like Levi’s or Coke. But the origins of logos and trademarks go back way further than that — back thousands of years, when merchants and craftspeople used “merchant’s marks” to designate the origins of goods and their authors.

But I was curious about how modern logos and trademarks emerged. It turns out that even though we think of logos and branding as global, they’re an essentially urban concept. They emerged to protect both businesses from the unfair competition across the street — as well as customers from being duped.

Those Ray-Bon sunglasses you bought from a street vendor in SoHo? That’s a trick that dates back hundreds of years.

First Came the Bakers

London in the 13th century was a booming city — it had begun installing pipes to deliver clean water, for example, and was enacting measures to keep the city relatively clean and orderly for its estimated 25,000 inhabitants. As more and more people congregated in European cities, more and more businesses sprang up — and competition flourished between bakers, brewers, artisans, and other craftspeople.

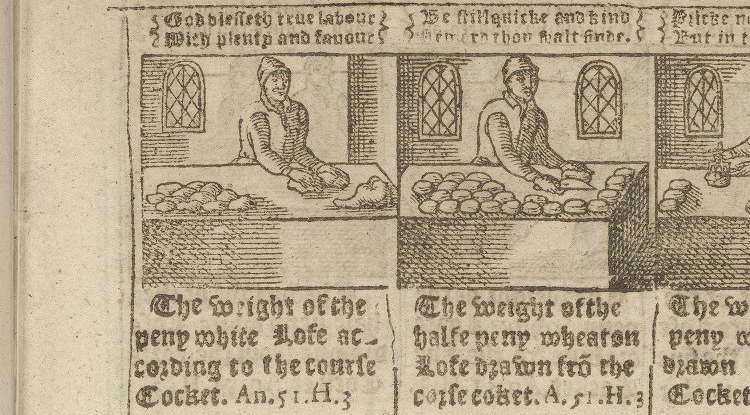

And with more businesses came more competition — and more swindlers. In roughly 1266, Henry III created what’s often called the first law regulating food in England: A set of rules called the Assize of Bread and Ale. The statute was designed to protect consumers from all sorts of nonsense by regulating the size and weight of bread and the purity of flour, as well as the prices tied to those items. This is supposedly how the “baker’s dozen” evolved: Bakers would plan an extra 13th loaf for every dozen, just in case one was underweight or not up to the Assize’s snuff.

It wasn’t just about protecting the public, though. The law was also about protecting greedy business owners from themselves, as a fascinating Harvard Law School trove explains:

Unscrupulous bakers could have increased the price of bread out of proportion to rising price of grain, and thousands would have starved, or perhaps taken vengeance on the bakers. Enforced by local bailiffs, these highly detailed regulations attempted to keep the populace fed while protecting bakers from a potentially angry mob.

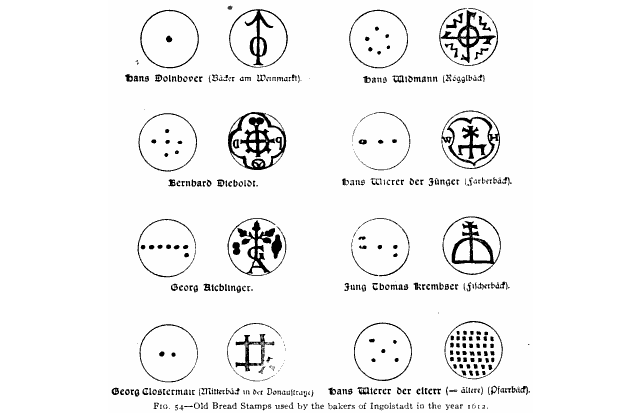

Which brings us back to logos. In order for regulators to correctly identify the origins of a loaf of bread, they needed a simple way to track the bread back to the source. So bakers were required to develop a “baker’s mark” to imprint all their products with a distinctive mark. This Bakers Marking Law is often credited as the first trademark law, and though few of the originals seem to survive, we can get a sense from these early 1600s marks from Germany — posted online by Elinor Strangewayes, who awesomely experimented with recreating the marks:

Strangewayes cites this image from The Baker’s Book: A practical hand book of the baking industry in all countries, from 1901.

These marks could be used to track down a baker that had shortchanged a customer or added sawdust to their flour. But they also let bakeries market themselves, which means these marks were an early form of branding.

Then Came the Brewers, and Everyone Else

If the Assize of 1266 is any indication, both bread and ale were at the forefront of life in European cities. And ale was just as tightly regulated as bread — if not more so. In Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, Judith Bennett describes how everything from quality, measurement, and price was monitored locally, and any brewer (often female) who failed to follow the rules was subject to “fines, forfeitures and even corporeal punishment.”

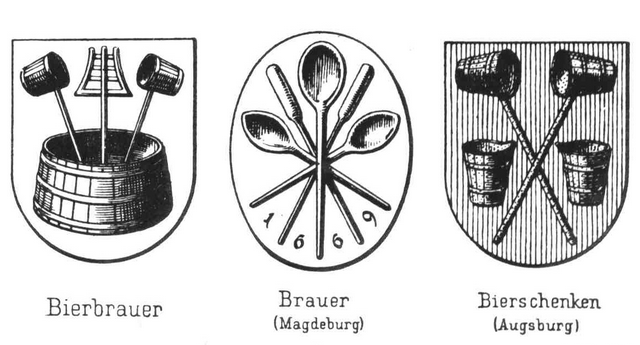

The strict rules — and threat of bodily harm — for brewers might help to explain why breweries were some of the first businesses to maintain logos and trademarks of their own. Another interesting guess is that as adding hops to beer became more common, the distances a beer could travel before spoiling grew longer — and brewer’s marks became necessary to connect a keg with its origin brewery.

Munich’s Lowenbrau, for example — now owned by Anheuser-Busch — started brewing beer around 1383. The company claims that its roaring lion logo emerged shortly after, which would make it one of the oldest continuously-used logos in the world. Around the same time in 1366, according to The Economics of Beer, tax records show the existence of a brewery called Den Hoorn, in Leuven, Brussels — it would eventually become Stella Artois, which even today uses the horn-bedecked logo of its 14th century processor:

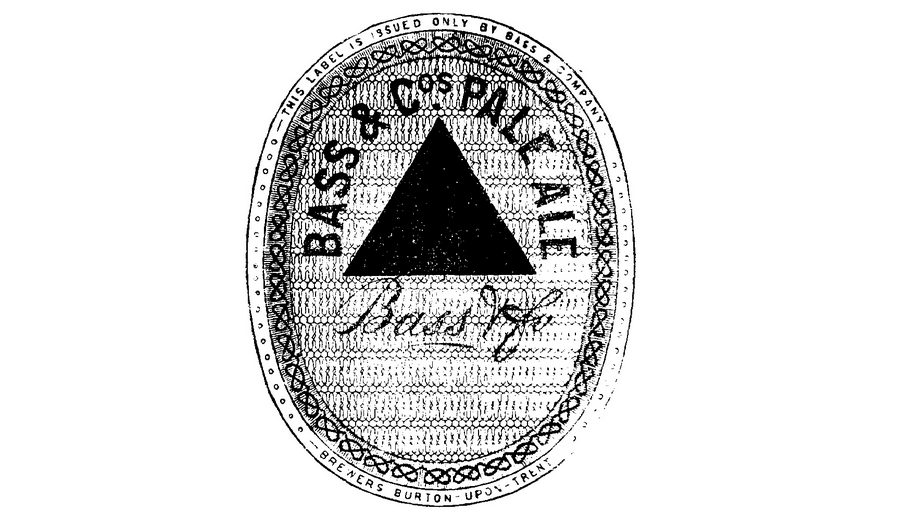

Both Stella and Lowenbrau can trace their logos back almost 700 years, but even modern trademark law is bound up with beer. In 1875, when the UK began accepting trademarks into its patent office, the very first application came from a brewery, Bass Ale, which ended up being granted its trademark on January 1, 1876, the first day of the act. Bass still holds England’s Trademark UK00000000001.

After all, beer is arguably as socially and culturally important to cities as bread. So maybe it’s not surprising that breweries hold many of the oldest trademarks on the books. The fact that breweries needed to protect the use of their names and logos meant that clients kept coming back, and that breweries were anchors of neighborhoods and whole cities for decade (or centuries).

As people flocked to Europe’s emerging cities in the 16th and 17th centuries, there were even more businesses, which meant even more customers and even more competition. Modern trademark law began to fill itself in between the cracks of the booming trade towns, as clothiers sued other clothiers for fraudulently using their marks, for example. So of course, there’s plenty more to say about how modern logos and trademarks evolved — but it’s fascinating to know that they emerged around the essentials of urban life: bread and beer.

Lead image: German brewer’s emblems. Via.