For 60 per cent of the world’s population, regular internet access is about as common as flying cars. Nearly five billion people today lack basic internet access either because they live in remote, rural areas or due to restrictive censorship on the part of the local government.

But where the internet has failed, the Outernet hopes to succeed. It’s working to get a new breed of satellite-based communication off the ground, promising to give even the most remote corners of the globe access to the whole of humanity’s collective knowledge.

The Outernet is the brainchild of the same-named New York-based tech company, a free content distribution system that would provide basic web access broadcast via a series of geostationary and LEO satellites, as well as cube sats using a combination of datacasting and User Datagram Protocols.

Datacasting is exactly what it sounds like: the wide area broadcast of data using radio waves rather than physical mediums (like cable, telephone or powerlines). User Datagram Protocols, or UDP, is very similar to conventional over-the-air radio or television broadcasts in that it’s uni-directional. The data is beamed from its source to any device within range and there’s no guarantee that it will be received, just like radio stations broadcast their signals without regard to which or how many radios are currently in range to catch it.

UDP is one of the most basic forms of Internet protocol. Invented back in 1980, it’s a connectionless transmission model — in that it doesn’t require someone to be on the other end of the line when the data is sent.

Radio for the digital age

In essence, the Outernet is a modern analogue to conventional radio broadcasts. The signal originates from a single, central location — originally a radio station’s broadcast tower, but, in this case, the Outernet HQ in NYC — and travels across a variety of wavelengths until it hits a suitable receiver — previously a pair of rabbit ears, now a 20-inch satellite dish — where the end user can flip between “stations” by modulating the received frequency.

But rather than rely on terrestrial radio stations, the Outernet bounces its signal up to a series of satellites then back down to a suitable receiver. This receiver doubles as a Wi-Fi hotspot then connects to a computer or mobile device and transfers the received data as a digital file. And since there is no two-way communication — just like you can’t talk to your radio and expect a reply — the system requires much lower bandwidth and, therefore, much less money to operate.

“When you talk about the internet, you talk about two main functions: communication and information access,” The company’s co-founder, Syed Karim, told the BBC. “It’s the communication part that makes it so expensive.”

Humanity’s public library

On the information side, the company has begun forming what it calls a “core archive” of knowledge based on information gleaned from 5,000 Wikipedia entries, Project Gutenberg, and a smattering of copyright-free e-books. The early plan — which definitely has some kinks to work out — is to crowdsource what content is broadcast and make decisions based on user requests and upvotes.

What’s more, since the system in uni-directional, it’s far more difficult to censor — just as shortwave radios served as vital information lifelines for those stuck behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. Initially funded by a news media investment company, Outernet’s mission is to provide free, anonymous, educational information, available to regions facing government censorship or otherwise off the grid.

In August this year, the startup started beaming this data across 200MB of leased geostationary satellite bandwidth, which reaches throughout North America and most of Western Europe, with plans to expand to the rest of the globe by July, 2015. Should the company’s IndieGoGo fundraising efforts work out, it could boost the daily broadcast limit to 100GB in the near future.

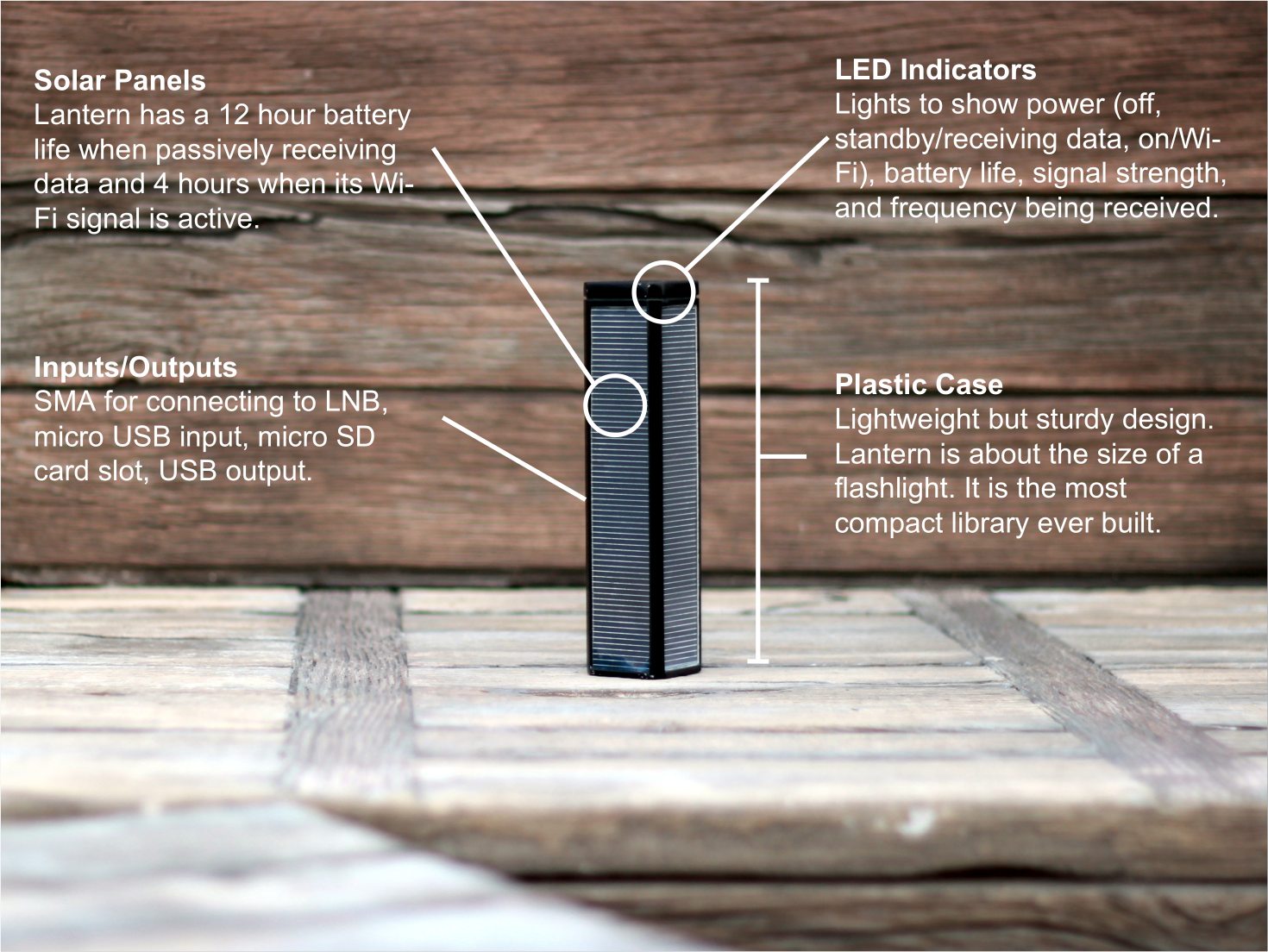

A single receiver in a central African village, according to Karim’s recent Ted Talk, could provide reams of valuable information to as many as 300 local residents — everything from agricultural texts to health, and human services. “If you were in the vicinity of a hotspot receiving the data from the satellite, you would be able to connect with Outernet on your phone and see Librarian — our index software — as if it was just an offline website,” he said. “There you would find the data, stored in files.”

In addition to disseminating evergreen information, the Outernet could very well also be used for emergency alert broadcasts which would be updated multiple times an hour instead of the average rate of once every week or so.

The plan is n0t quite perfect, however, as Mark Newman from the technology research firm Ovum, pointed out to the BBC:

When you start to think about the needs of rural communities in developing markets, what they are going to be most interested in are things that impact their daily lives – subsistence, crops, weather and healthcare. I question whether by sourcing content centrally and distributing it locally, you will meet those local needs – both in terms of content and language. Literacy is also going to be an issue. Delivery by audio rather than text would be something to look at, but that would use up more data.

An ambitious project

Still, some internet is way better than no internet. And with estimates placing global internet reach on par with what Outernet can provide still 15 to 20 years away, the Outernet could provide a valuable stop-gap service until conventional ‘net access becomes viable.

To that end, Outernet has partnered with the World Bank in South Sudan to perform a test run of the service next July. Should it prove successful, the company hopes to increase its coverage area and begin offering the self-contained receivers, called “lanterns”, from its Indiegogo campaign around that time.

And even if the Outernet itself fails to take off, it is far from the only free access system currently in development. Two of the biggest names in tech have already thrown their weight behind similar strategies. Google’s LA Times – Indigogo – Wiki – BBC]