In a dusty, seemingly empty field 100km east of Los Angeles, Dr Alexis Grey, a forensic anthropologist from the San Bernardino County Sheriff Department, points to a chain-link fence far in the distance, the mountains rising beyond in the hazy heat. “There are 7000 people between us and that next fence there,” she says. For almost a decade, her job has been to confirm the identification of every single one of them.

From 1908 to 2008, this three-acre plot at the edge of one of San Bernardino’s cemeteries was the final resting place for most of the county’s unidentified burials. Not all of the bodies here are unknown: Many of the burials are indigent, meaning that next of kin couldn’t afford a proper funeral or no one stepped forward to pay for one. But about 10 per cent of the people here — around 700 people — were buried without a name. Some are clearly the victims of murders or kidnappings, but most simply erased themselves from society. The county paid for their funerals, and made sure they were properly interred. Yet decades later — over a century later in some cases — no one knows who they are.

Rusted coffin handles sit over a stone grave marker. Many of the people at this site were buried 70 to 80 years ago.

Over the last few years, thanks to advances in forensic science, these people now have a better chance of being identified. Since 2006, Grey and her team have been exhuming the unidentified bodies, confirming the descriptions with burial records, and sending a sample of the remains to Northern California for DNA testing.

So far, they have exhumed 79 bodies. They have identified eight people.

Giving Names to the Dead

The San Bernardino County Unidentified Persons Project is one of many initiatives in the state which were launched in the wake of the 2001 California State Senate Bill 297, which required counties to use modern DNA analysis to identify any unknown remains. The only hitch, and what has been holding up the process for many counties, is there is no financial backing allocated with the bill to get these identifications on the books. Which means scientists had to get creative.

Talking fast with clipped syllables, her hair pulled into a ponytail under her white Stetson, Grey could easily be cast as a whip-smart forensic star of CSI: San Bernardino (in fact, she’s been an advisor to the show Bones). It is not surprising that it was her idea to turn the San Bernardino project into a study program for students through the Institute for Field Research.

“If we had a private company come in here like a mortuary and used their backhoe, each disinterment would cost about $US2000,” says Grey. “By turning it into a field school, it becomes a really unique experience — there’s really nothing else like this in the country.” So instead of spending their summer holidays at the beach, or even working in an air-conditioned lab, these two dozen students have elected to dig up graves in 40C heat.

Grey, in the white hat, stands next to Dr Craig Goralski and gives notes to students who are examining a body.

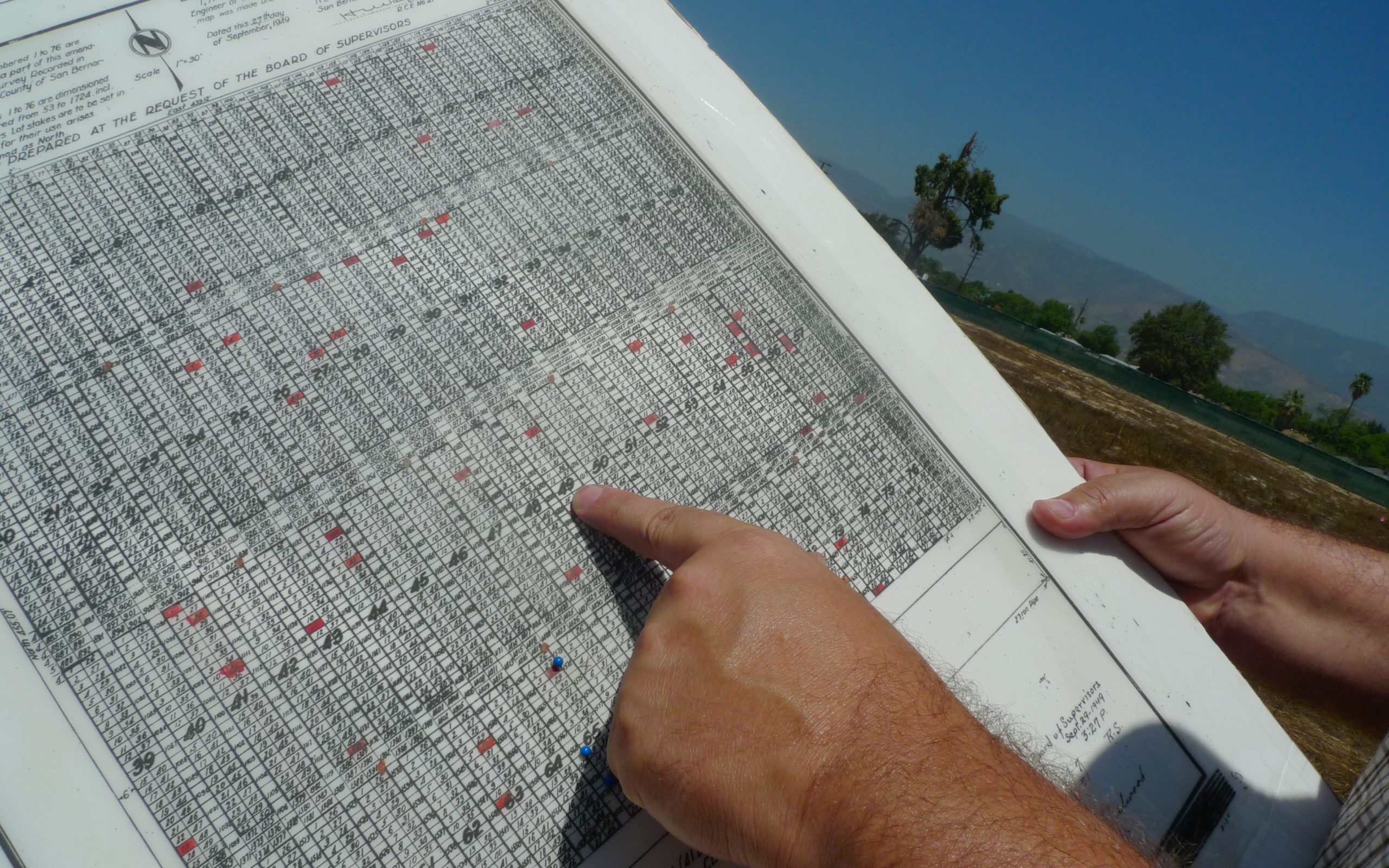

But some of these students will go on to work in equally uncomfortable or dangerous conditions, identifying victims of genocide or natural disasters. “We’re teaching them how to collect DNA, but we’re also teaching some of these techniques that some of these students will use in other parts of the world like Bosnia or Argentina, places where they have mass graves of the disappeared,” says Grey. In these places they might not have the luxury of GPS or satellite imagery, which also happens to be the case here. She holds up a piece of foam core to illustrate what kind of information students are working with: A 1949 map of the cemetery created by the county’s Board of Supervisors.

The map, with each plot numbered to correspond with burial records, is mostly correct: The graves are arranged in a rough chronological order and have engraved stone markers buried at the corner of each coffin. But as they have discovered already, the map does not account for improvisation over the years. Some gravediggers opted for narrower graves than what were prescribed, shifting an entire row off by a metre in an effort to save space. The width of the aisles between graves grows and shrinks based on the transportation technology used for burials — wagons, trucks, backhoes. The fence used as a reference seems to have been moved three times.

The not-very-reliable 1949 map shows where the 7000 graves are located, kinda.

Ground-penetrating radar, which could usually be employed to locate a single grave, doesn’t work well here — there are too many bodies, too close together, and it’s hard to tell where one grave ends and another begins. Using a compass and a shovel, they have to make an educated guess and start digging. Once they have located the bodies, they’re able to geotag the location and use a total station (what traffic engineers use to build streets) to place it onto their revised grid. Her team is essentially digitising a 65-year-old burial map by hand.

Exhuming the Bodies

Today, four groups are clustered beneath bright blue tents that provide much-needed shade for their worksites. They will each access and analyse a single grave today, a painstaking process due to the nature of an indigent, county-funded burial: Most “coffins”, if you can even call them that, were made from pressboard and have completely deteriorated. Some, due to 500kg of soil pressing down upon them over a century, have collapsed into their occupants, shattering critical bones. It’s delicate work, and Grey’s program partner, anthropologist Dr Craig Goralski, walks me through it.

Wood from a deteriorating coffin peeking through the dirt at a gravesite.

The students begin with shovels. About two or three feet down, they will tap against wood — whatever fragments of the coffin exist, which are lifted off and placed to the side. Then they move to trowels, then chopsticks, then brushes, to ensure that they don’t damage the bodies. They dust off and photograph the remains. Then comes the critical moment: Measuring the bones for clues of age, sex and ancestry. This is how they will know if they have dug up the correct John or Jane Doe.

Cross-referencing the map with the cemetery’s and county’s own records can usually help them confirm the description of who they have exhumed. For each body, there is a coroner’s report which outlines basic anatomical information, including any potential trauma, which is often the most helpful. “If we know that the John Doe we’re looking for had a gunshot wound to the chest and one of their ribs are cracked, we can see that to make sure we got the right guy,” says Goralski. “We need to come to the same conclusions that the coroner came to 60 years ago.”

The bodies are draped in a body bag with all relevant information written on the outside and reburied. None of the remains leave the cemetery.

One detail they often do need to amend, however, is the coroner’s assessment of race. “We’re finding that how ancestry was reported in the past is very different from where we report it now,” says Goralski. Back then, the go-to race for anyone who wasn’t white or black was “Mexican,” even though the person might not even be of Hispanic origin. Here, the team looks for all sorts of osteological markers, skeletal cues which are particular to certain ethnic backgrounds. Shovel-shaped incisors, for example, are a signature feature of many Native American cultures — who might have originally just been labelled “Mexican.”

After confirmation, a part of the body needs to be sent to the state’s Department of Justice for DNA analysis. While the labs used to prefer a bone as large and dense as a femur, they now don’t need as much to get an accurate sampling. “Toes have been proving surprisingly helpful,” says Grey. “We used to go for teeth, and if the teeth are still in the mandible, we will do that. But usually we’re losing a toe.”

Making a DNA Match

It’s at this point that all the information collected by the program goes into the hands of Deputy Bob Hunter, an investigator for the San Bernardino County Sheriff-Coroner, who works with the Department of Justice on all the cases that come out of the field here. “We’ll send a bone from an unknown person up to Sacramento — the actual facility is in Richmond, California — and if they can get alleles out of it, then it goes into the CODIS nationwide database,” Hunter tells me.

Although DNA sampling is high-tech, most of the tools used in the field are old-school, like sifters to find bone fragments.

CODIS is the Combined DNA Index System that’s run by the FBI, a nationwide program that’s responsible for sampling and analysing DNA. Although DNA profiling has been somewhat reliable for the past decade, the tech has improved most dramatically in the last few years, says Hunter. “There are even some older cases that we’ve resampled in the last year and were finally able to get DNA from.” But even with a good sample, CODIS needs to have something to match it to: A relative of the unknown person must also have submitted their DNA to the system, either voluntarily or through a previous criminal investigation.

Which means sometimes Hunter is back on the paper trail. Using all the biometric information confirmed (or updated) by the exhuming process, he’ll dive into the county records, which date back to 1890, or pore over old newspapers. Normally, he wouldn’t have the staff to tackle all these unsolved cases, but with the new leads developed by this research, he’s often able to fill in some blanks. “We are so lucky that IFR put this program together,” he says. “This lets us take these older cases and get them back in the system.”

The graves being exhumed today are four of about 30 that the program will address this year.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that the state shares their sense of urgency. There is one part of the process that is out of their hands: The waiting game played with California’s DNA lab, where their scientists must focus on current homicides first. While some results from the Unidentified Persons Project have come back as quickly as several months, they’re still waiting on other cases which were exhumed in 2004. “These are the coldest of cold cases,” says Goralski. “We don’t get priority on these things.”

But there is something to seeing the cold case being resurfaced — both literally and figuratively — through this project. Recently they’d exhumed a man found in a nearby field who was determined to have died of acute alcohol poisoning. This was a case so cold that the letter from the FBI in the file was signed by J. Edgar Hoover. I was able to see the entire case — an autopsy report, newspaper clippings, photographs of the crime scene, the coroner’s estimation of “Mexican” which I now knew to be specious since that label was applied to most people of colour. All of that, compounded with the fact that his body was buried in a plot a few feet from where I stood, it all suddenly made him more of a person.

I still can’t stop thinking about him. Would they ever find this man’s family? Did anyone even care that he was gone?

Finding Closure for Families

As we sipped Gatorade under one of the blue tents, Grey tells me about a girl who had disappeared in the mountains while walking to school in the 1960s. “There’s always a little bit of luck involved because we need the families of the missing to also have submitted their DNA,” she says. “But in this case, her sister had not given up.” When they exhumed a body in 2012 the state found a genetic match — the sister of the missing girl had indeed registered her DNA with the state in the off-chance that her sibling might someday be found. Both her sister and her mother were still alive. Grey was able to give closure to this family, 40 years later.

“That was worth every second of this heat because I’m a mum,” she says, her signature rat-a-tat speech slowing and her eyes softening. “I can’t imagine my child being missing for 40 years. That’s why we do what we do.”

A gravesite that has been exhumed, investigated, and outfitted with a new digital marker, and is now being reburied. DNA results might not come back for years.

Requiring every Californian to undergo DNA profiling would be a controversial and highly contentious issue, and there’s probably zero chance that the state would ever enact any kind of mandatory registration. But if there was a point I walked away from the cemetery with, it was this: If you’re missing someone, anyone, get your DNA registered. Even if you don’t have a family member you’re looking for, Grey recommends submitting your DNA anyway. “What if they can’t speak for themselves? What if they got in an accident and they are unable to talk? A DNA profile would help us figure out who to call.”

A few minutes later, Grey was back on high-speed mode, quizzing members of her team with a series of rapid-fire questions. “Look at the subpubic angle there, would you call that narrow or wide?” “The holes in the skull, do you see one or two?” As the forensic anthropologist for one of the largest counties, area-wise, in the contiguous US, Grey has to cover many cases, on massive amounts of ground, and she doesn’t have the luxury of time. She’s teaching the students to be just as hyper-efficient.

But there’s another reason for this project to move fast. The oldest person they have exhumed so far was determined to have died in 1927. The chance of any of these unknown people having surviving parents or siblings gets smaller with each passing day.

Pictures: Alissa Walker