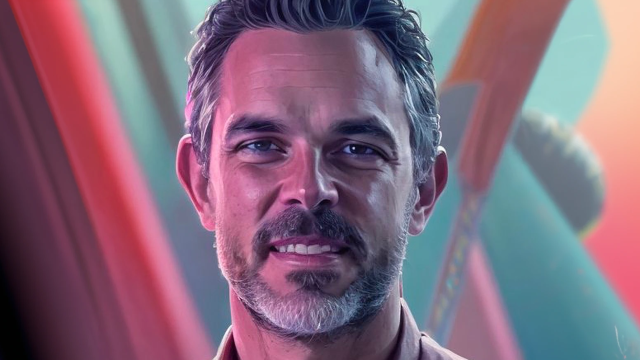

When people start complaining that your tech company is ruining the world, you hire a guy like Rob Leathern. He joined Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook, just as the Cambridge Analytica scandal convinced the public that Facebook was an existential threat to democracy. During the 2020 election and coronavirus pandemic outbreak, Leathern led efforts to address privacy, misinformation, and other problems in Facebook’s advertising system. Right after the election, Google poached him, bringing Leathern on as vice president in charge of products related to privacy and security — just as regulators embarked a years-long effort to ramp up scrutiny on the search giant.

Now after two years at Google, Leathern is out. He tweeted that Friday was his last day at the company. Leathern agreed to hop on the phone with Gizmodo, and while he didn’t explain why he left Google or where he’s going next, he did have a lot to say about one topic: these days, the public face of big problems at big tech wants to talk about artificial intelligence.

Leathern’s background gives him unusual insight on what must happen as the world wraps its mind around tools like ChatGPT and how businesses like OpenAI grow exponentially.

In the early 2010s, blind optimism and fast money in Silicon Valley shielded the tech giants from critics. Things are different now. Almost as fast as AI chatbots captured the public’s attention, we started talking about whether the technology will destroy us all. In the immediate future, companies like OpenAI, Google, and Microsoft need to ramp up programs that allow them to say “we hear your concerns, but don’t worry, we’ve got it all under control.” Leathern knows how to run that kind of operation.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Thomas Germain: Looking at the last few years of your career, you’ve been someone who jumped from company to company addressing some of the biggest societal issues in the tech world. How do you see the moment we’re living through with AI?

Rob Leathern: Yeah. I joined Facebook to work on integrity stuff in 2017, and it kind of reminds me of the situation we were in then. AI sort of feels like social media did in 2015 or 2016, there was an opportunity to build a bunch of systems to address big problems, but no one was necessarily doing it yet. I think we’re at that same kind of inflection point, but we’re moving even more rapidly. I mean, these tools, by their very nature, have so many more feedback loops embedded in them. The pace of change is insane, so this is the right time to be thinking about this stuff.

TG: So I know you’re not a technical expert on AI, but as a tech insider, do you have any thoughts on exactly how far past the Rubicon we are?

RL: I think there are people better positioned to answer that question than me, but what I can say is there’s an incredible amount of momentum that creates pressure for folks on both sides, and the incentive to move quickly worries me. There’s a lot of pressure for companies to keep making advances, figure out how to train the next model, or reach the next milestone.

Then what I’ve seen from my work on privacy over the last six years is there’s pressure on the other side of the coin as well. Regulators are competing with each other too, and everybody wants to be seen as pushing back on these advances. In other words, there are competing incentives in every direction to move faster and less carefully than you might otherwise. At the same time, some companies also have pressure to hold some things back more than they might like to.

TG: Right, there’s some real tension there. OpenAI has an incentive to move as fast as possible to prove its a leader. Older players like Google and Microsoft have demonstrated that they’re keeping up, but they have more of a responsibility to be seen as moving carefully and methodically.

RL: Yeah, it’s going to be really interesting to watch those dynamics play out. The bigger companies are under more scrutiny, so they have to move slower and have checks and balances in place. In some cases, that’s going to lead to talented folks getting frustrated and wanting to leave. Really, it’s the spillover effect of the past challenges they’ve had around issues like privacy and security, and the regulations that came out of it. That has a huge impact on their agility.

TG: How do companies working on AI balance moving quickly and moving responsibly?

RL: We’re at this transition point where, you know, AI ethics researchers who’ve been writing white papers have been doing great work. But maybe now is the time to transition to folks who have more hands-on experience with safety, integrity, and trust. This is going to touch a lot of different areas. It can be things as seemingly small as monitoring the identities of developers in the API ecosystem [the systems that let outside companies access a tech company’s products]. That was one thing that came out of the Cambridge Analytica issue at Facebook, for example. You need to start getting those folks in place, and my supposition is that not they’re not quite there yet when it comes to AI at most of these big tech companies.

TG: Looking at the conversation around AI, it seems like we’re having this conversation much, much earlier in the process than we did with social media ten years ago. Is that because we’ve learned some lessons, or is it because the technology is moving so fast?

RL: I think it’s a bit of both, and it’s not just the speed, but the accessibility of these systems. The fact that so many people have played with MidJourney or ChatGPT gives people a sense of both what the upsides and the downsides of the technology could be.

I do think we’ve learned some lessons from the past, as well. and we’ve seen various companies create mechanisms to address these concerns. A whole generation of engineers, product managers, designers, and data scientists work on these societal problems in the context of social networks, whether its privacy, content moderation, misinformation or what have you.

TG: Like with so many of these issues, some — but not all — of the concerns about AI are vague and hypothetical. What are the big things you’re worried about?

RL: Well everyone is so focused on the big changes, but I think it’s interesting to look at some of what’s going to happen on the micro scale. I think the problems are going to be a lot more subtle than we’re used to. Take the other side of deep fakes. We’ve heard about water marketing content from ChatGPT or image generators, but what are you going to prove that a picture you took is a real photo. Tagging pictures with location and some kind of personal identifier is one solution, but then you’re creating these new signals that can pose privacy issues.

Another non-obvious concern is that anyone can use the free versions of these tools, but the paid and more powerful versions are less accessible. AI could potentially be problematic from an equity perspective, creating yet another way for wealthy folks to have an advantage. That will play out with individuals, but also with businesses on the client side. This technology is going to further separate the haves and have nots.

TG: Given the nature of this technology, it’s hard to imagine what regulators can even do about it. The business friendly government in the United States, for example, is not about to ban this technology. Is it too late?

RL: Well, there are requirements that you could think of that governments can put in place. Maybe you have to register your technology, for example, if you’re using more than x number of GPUs or whatever the right metric is. But you’re still going to have people who are running their unlicensed technology in a basement, and whatever scheme we come up foreign governments aren’t going to care. I think to a certain extent the toothpaste is out of the tube, and it’s going to be hard to put it back in there.

TG: I’ve been reporting on privacy for the better part of a decade. In that arena, it feels like just in the past year regulators and lawmakers are truly grasping the digital economy for the first time. AI is an even bigger problem to wrap your heads around. Are you hopeful about the ability to regulate this space? The prospects feel pretty abysmal.

RL: We’re in for a very challenging time. I think we’ll end up with a patchwork of regulations that are just copy and pasted from other things that don’t play well with each other. But people are more attuned to the facts of this situation. I don’t think the right answer is to make some blanked statement that we need to slow things down, because again, less well-intentioned actors like China are going to move ahead.

One interesting lesson that comes from working on privacy and security is that in the early days, you have folks that see just how bad the gaps are, and they fall on the side of shutting things down. But to be effective in these roles, you need to have an appreciation for both downside risk as well as the upside potential. I used to say you need to be kind of an optimistic pessimist. There’s an opportunity to create rules, policies, and implementations that can actually allow the good stuff to flower while still reducing the harms.

TG: That’s a pretty industry-friendly perspective, but you’ve got a point. Our government is not about to shut down OpenAI. The only hope is a solution that works within the system.

RL: Right. If you take the ‘shut it all down’ approach, well, among other things it’s just not going to happen. You need the adversarial folks, but you need optimists in your portfolio as well. And look, the other thing that also is true is it’s really hard, right? Because you’re creating stuff that hasn’t existed before. There aren’t always great analogs to something like ‘how do I make a given tool private?’ And like I used to say when I was speaking on behalf of Facebook, you’d be truly amazed at how innovative the bad guys could be. They do incident reviews too. They share knowledge and data. It’s going to be an incredibly adversarial space.

TG: I want to ask you about a completely different topic if you’ll indulge me, and that’s TikTok. What I’ve been saying in my reporting is a lot of concerns are overblown, and discussions about banning TikTok or ByteDance seem like a useless exercise given how leaky advertising technology is. But you’ve got perspective from inside the tech business. Am I wrong?

RL: Your take accords with my feelings about this. Look, it’s important to, you know, ask questions about the ownership and the structure of these organisations. But I agree, the idea of a ban isn’t going to have all the benefits that some people presume it would. Companies like TikTok need to have a better story, and a better reality, about ownership and control, and where people’s data is going, and what the oversights and controls are. But banning it doesn’t sound like the right solution.

TG: On the other hand, you hear TikTok going on and on about this ‘Project Texas,’ where they plan on housing all the data on servers in the US. And sure, it’s a fine idea, you might as well. But talking about the physical location of a server as though that should reassure anyone seems ridiculous. Does that feel meaningful to you?

RL: These systems are complicated, and saying oh it’s all on server X versus server Y doesn’t matter. What would be more reassuring is the additional oversight, but then again, those things are pretty challenging to set up too. People are looking for a level of certainty on this issue that’s hard to come by. In fact, any certainty we do get may just be hallucinatory.