An international team of scientists says all-female termite colonies from Japan are the result of accidental hybridisation, and that their highly robust nature makes them an ecological threat.

A new paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explains the surprising presence of all-female termite colonies in Japan. These colonies — the only all-female termites known to exist — likely came into existence last century, the result of one lineage interbreeding with another, according to the study, led by entomologist Nathan Lo from the University of Sydney in Australia. These termites are potentially bad news, as they could out-muscle native populations and spread to other parts of the world.

“We already have a number of very damaging termite species here [in Australia]. However, our study highlights the importance of making sure termites from overseas are not permitted to establish themselves,” said Lo in a University of Sydney press release. “If they were to hybridise with our local termites, it might lead to even nastier lineages of termites for homeowners to deal with.”

Indeed, the all-female hybrids appear to be stronger than their non-hybrid versions. What’s more, the females clone themselves, so they don’t need males to procreate. These asexual colonies, therefore, can grow at twice the rate of sexual populations, as only females are needed for reproduction. The presence of these all-female colonies suggests males aren’t always needed to maintain complex animal societies, in what is a fascinating discovery.

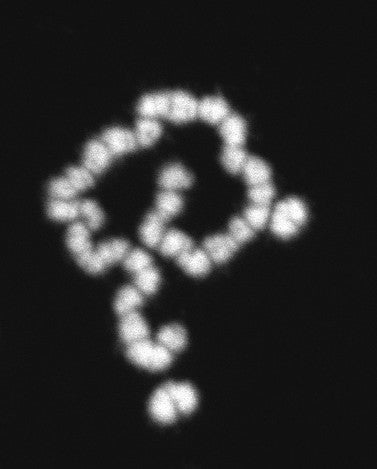

The same team of researchers first described these drywood forest-dwelling termites in 2018. They belong to the species Glyptotermes nakajimai, and they can be found in the southern areas of mainland Japan and on the islands to the south.

Termites typically engage in sexual reproduction, in which both male and female gametes (sex cells) are required to produce offspring. Asexual reproduction is enabled by parthenogenesis, in which an embryo spontaneously appears in an unfertilized egg cell. Some species of bees and ants live in all-female colonies, but they still require males for reproduction. The hybrid termites from Japan are unique in that males are completely absent.

The purpose of the new study was to analyse the genetic structure of the species as a whole, to determine how sexual and asexual individuals might be related to each other, and study the chromosomes of males. Another key goal was to investigate the reason for the asexual colonies and determine if hybridisation was the true cause. To that end, the team studied drywood termite colonies across several Japanese islands.

That the all-female colonies are a result of hybridisation appears to be the case, as it’s best “explained through intraspecific hybridizations between sexual lineages having different chromosome numbers,” as the authors write. The scientists hypothesize that females from one colony interbred with males from another colony. This happened last century as one lineage was unknowingly transported from a smaller island to mainland Japan, probably by boat.

Interbreeding tends to be a bad thing, as it can introduce bad mutations. Here, however, the hybridisation has resulted in a robust and potentially problematic offshoot. The highly adaptable drywood termites don’t require moist conditions for burrowing, making them a potent ecological threat.

The chromosome analysis led to the discovery of a strange genetic feature among males: they feature either 15 Y or 15 X chromosomes, instead of a single Y or X chromosome. The scientists speculate that this is an evolutionary response to inbreeding, which is common among termites.

“Termite offspring can inherit nests from their parents, saving them the trouble of venturing into the dangers of the outside world, burrowing into wood, and creating their own nests,” Lo explained. “The problem with nest inheritance is that it results in a lot of inbreeding — sisters mate with brothers, and offspring may even mate with parents.”

So by evolving multiple Y chromosomes, male termites pack a ton of genetic diversity, allowing close siblings to mate without deleterious genetic consequences, according to the paper. That said, this added genetic diversity didn’t seem to have a bearing on the appearance of the all-female hybrids. As the scientists write in the study: “Our results indicate that asexuality has enabled females to supplant a key role of males.”

Entomologists and conservations now need to be on alert for these all-female colonies. Australia is particularly sensitive to invasive species, requiring extra vigilance. These colonies don’t currently pose a risk, but here’s to hoping it stays that way.