On the shores of a Scottish loch lie geologic deposits dating back a billion years, and within the rocks is evidence of the earliest known non-marine multicellular organism, according to a study published in Current Biology. It’s a fascinating new detail in the story of how animals may have evolved from the soup of early Earth.

A team of microscopists, geologists, palynologists, and paleobiologists excavated and described the fossil microorganism, which they named Bicellum brasieri. It appears to be a member of holozoa, the group of organisms that contains animals and their single-celled relatives, but not fungi. The rock deposit from which the fossil emerged, on the beaches of Loch Torridon in Scotland, has been studied for years; in 2011, a Nature paper by the same team described the assemblages at greater length. The new paper dives into the singular complexity of B. brasieri.

“We have found a primitive spherical organism made up of an arrangement of two distinct cell types, the first step towards a complex multicellular structure,” said Charles Wellman, a paleobiologist at the University of Sheffield, in a university press release, adding that it’s “something which has never been described before in the fossil record.”

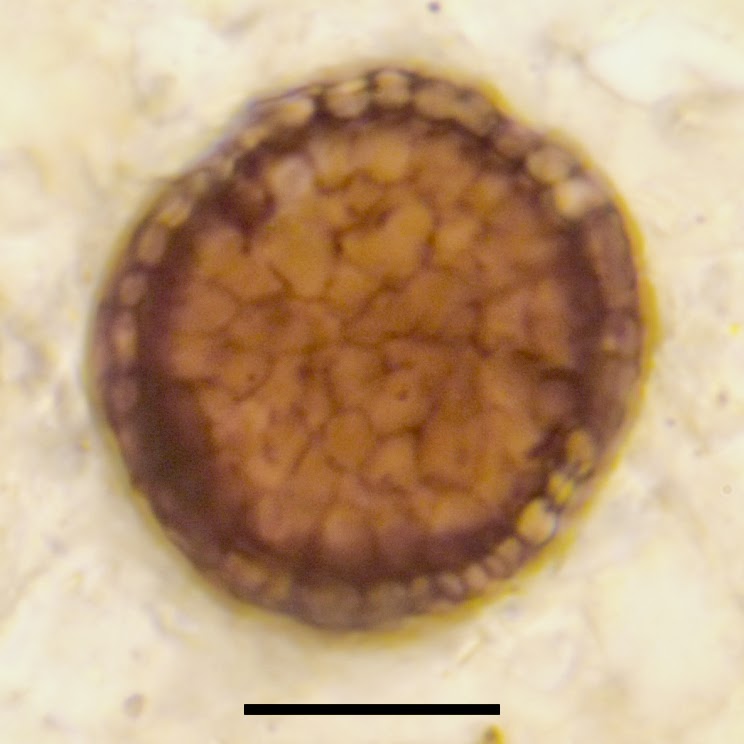

The fossil is constituted by a stereoblast of tightly packed cells surrounded by a layer of sausage-shaped cells. It’s tough to determine exactly what the functions of the two different cell types were, though it’s possible they may have had some reproductive implications.

In order for life to make the monumental shift from simple unicellular organisms to complex multicellular ones, “organisms had to evolve a genome that controlled the nature of cell division and how cells stick together and how they differentiate and segregate tissues,” said Paul Strother, a paleobiologist at Boston College and lead author of the new study, in a phone call. “The thing that’s exciting about this fossil is that even though it’s an extremely simple morphology, it clearly had the capabilities of some of these fundamental features needed to become multicellular.”

Being so simple yet multicellular, this billion-year-old blob seems most closely related to the holozoan groups of Ichthyosporea and Pluriformea, some unicellular microorganisms, according to the researchers. Importantly, the rock deposit from which B. basieri emerged was a freshwater environment, as opposed to the marine environments typically linked to the emergence of complex life. Earlier discoveries have confirmed the existence of such ancient multicellular life in oceans, some dating back over two billion years; it now seems possible that more than one evolutionary pathway led to the first multicellular lifeforms.

The Torridonian deposits off the loch may hold more ancient microscopic life to inspect. It seems there may have been multiple cauldrons of life burbling away so long ago, cooking up a diverse array of early lifeforms to evolve into the animals we know today.