My ex was the first person to tell me about Q. This was near the end of 2016, and we were in the beginning stages of our relationship. I took it as us having the same, passive interest in conspiracy theories. The kind of interest where you go, “LOL sounds like a Dan Brown novel!” I laughed it off, but he dug deeper and continued to dig deeper after we split soon after the election. Good thing too, since he turned into something more than a simple QAnon believer.

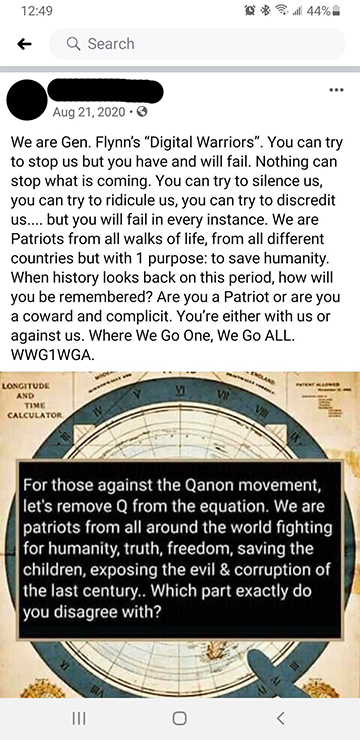

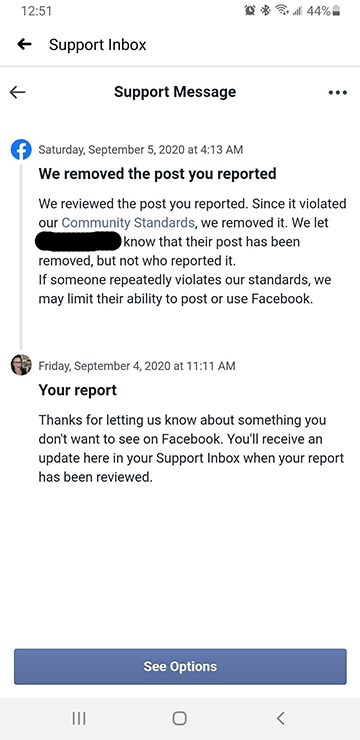

He turned into someone who made it his mission to “wake people up,” introduce them to far-right Facebook groups where talks of civil war weren’t simply an insurrectionist fantasy, but a real plan. One post I reported to Facebook, which it removed, was a call for Trump supporters to take up arms and get ready for battle. There was no veil in the threat of violence.

He posted photos of himself at the 2020 Richmond gun rally, AR-15 long barrel rifle slung over his shoulder, with captions that read, “When the #Boogaloo commences, you know we’ll be there!” I haven’t spoken to him since 2017, but I keep tabs on his public social media accounts in case I needed to provide information to law enforcement. That’s how much he scares me.

But it wasn’t just him. After the 2016 election, a distinct split between my friend groups on social media, Facebook in particular, emerged. While most of us were in the Bernie or Hilary camp, those who became Trump supporters were mostly white, male, and military veterans.

The pieces didn’t start to fall together for me until January 2020 (way later than it should have happened), after the first covid-19 case was recorded in the U.S. That’s when I and those friends cut ties with those people — on Facebook and in real life. These were people we went to high school with. Our family members. Best friends’ significant others. People we will likely never talk to again. One conversation, in particular, ended in myself and seven other people cutting ties with someone we had known for over 15 years.

What began as an exchange about an anti-Black Lives Matter protester getting into a physical altercation with some BLM protesters devolved into me being accused of being biased and “victim blaming” the man with a “FUCK BLM” sign. It progressed into an exchange about a KKK rally that turned violent in Anaheim, California. By then, a mutual friend was declaring that the KKK had the right to their opinions, asking, in so many words, when did a “random” person’s opinion ever hurt anyone directly, on the thread that he presumably thought was magically visible to only people who have never been victims of racism.

The conversation quickly deteriorated. More mutual friends joined in to futilely try to explain that the KKK’s white supremacist views have tangible, real-life, devastating consequences that have been documented since the deadly hate group’s inception. The soon-to-be-former friend argued that short of directly advocating violence, the KKK had the right to espouse hate freely, seemingly without consequences. In the end, we all unfriended him and he ended up blocking me after that.

The belief that it is OK to just say whatever hateful thing you want — even when spreading dangerous conspiracy theories from a position of influence and power — has been manifesting in our government for years.

Just look at Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s outlandish allegations straight from the QAnon playbook about the 2018 California wildfires: Those were caused by Jews operating a laser from space to clear a path for a high-speed railway, she claimed. She’s been posting conspiracy theories like that to social media for years, drawing people into her dangerous way of thinking.

Greene’s has since been kicked off both her congressional committees for espousing QAnon conspiracy theories, but the damage was done. This shit spread all over Facebook. It was spread by friends. Aunts. Uncles. Randos who you can’t remember how they got on your friends list in the first place. It didn’t matter how many times I cited someone I knew who worked for PG&E, who worked on those exact power lines that caused the fire, or how many news articles and reports I tossed their way.

At the same time, the more I fought some of my own Facebook friends on unfounded theories like this to stop the spread of misinformation and hatred, the faster they unfriended and blocked me — if I didn’t get around to it first. Take my friend David* (not his real name).

It’d been a while since pictures of David’s adorable 6-month-old baby graced my Facebook timeline. Concerned by the lack of cuteness, I typed his name into the search bar and discovered his profile didn’t exist. Did he delete his account? Turns out he didn’t. Our mutual friends were still tagging him in posts, but I couldn’t see anything he wrote. I couldn’t click on his name to take me to his profile. I asked one of our mutual friends about it who said, “Sounds like he blocked you.”

That’s exactly what he did. No warning beforehand. No major blow-ups between us, aside from the time I asked him, “Why in the ever-living-fuck would you vote for Trump?” “I have my reasons, which I will not share here,” he said. I don’t know how long after he blocked me, but that was our last conversation. One of our mutual friends asked him why he blocked me. “She’s media. She can’t be trusted,” David told him.

That was back in November 2020, and considering everything that has happened in this country during the last two months alone, I probably would have ended up purging him from my friends list anyway, as I, since then, have blocked every QAnon follower and Trump supporter on my friends list. I’d rather not have my timeline trashed with cultish posts. I mean, Facebook certainly did not do anything to address QAnon on its platform until it was too late.

When a person close to you has fallen down that rabbit hole, when you’re left shouting into the void with nothing but anger and pain, sometimes the only solution is to unfriend and move on. That’s easier said than done, especially when it’s family. If they do ever manage to see the error of their ways, do you welcome them back into your life? I believe in redemption, but I also believe in personal boundaries.

The issue here is trust. What happens when a former partner or friend or family member decides to crawl back into your life? There is a reason why white supremacist groups target QAnon followers for recruitment. How can you be sure that the friend that once so easily fell for tales of pedophile cannibal Democrats running a massive child-sex-trafficking cabal isn’t into adjacent far-right garbage? In my friend-losing experience, QAnon and further deprecation of already marginalised groups went hand-in-hand.

The question I’m struggling with is a common one for someone who has, over decades, retained connections with people from all walks of life. I have been driven by a sense of personal responsibility to connect, to grab onto whatever commonality I have left with someone I once knew as their grasp on reality begins to slip, as their views turn from misguided to threatening and inexcusable. After decades of throwing facts their way, of battling it out in endless comment threads on social media and hitting wall after wall after wall, at what point do you stop feeling like it’s your job to “fix” them? And at what point, do you decide enough is enough?