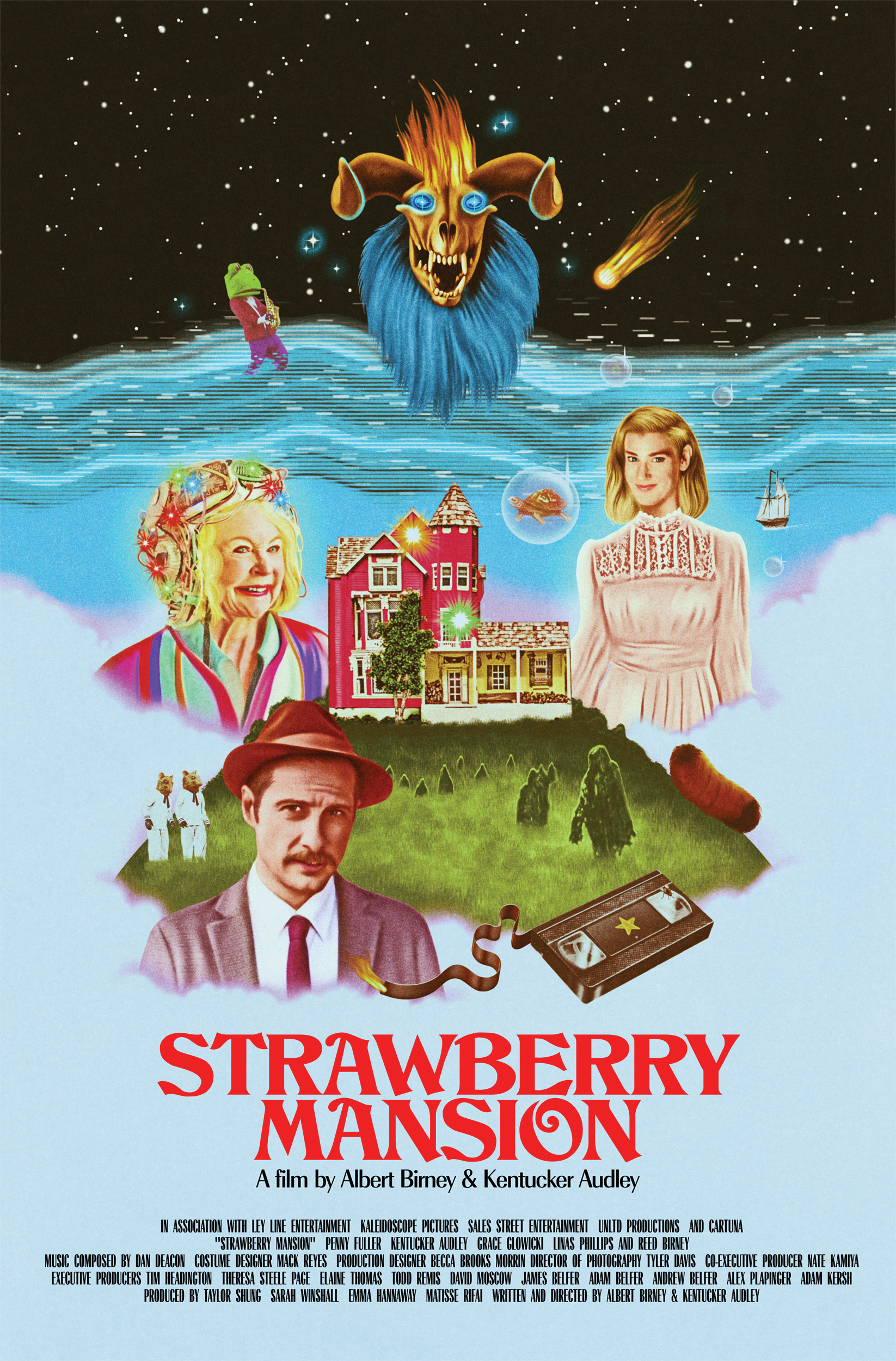

Writing-directing duo Albert Birney and Kentucker Audley’s Strawberry Mansion imagines a world where the time people spend fast asleep isn’t truly their own. Instead, it’s the latest frontier where both businesses and the government see money-making opportunities that people usually only have to deal with in the waking world.

While there are a fair number of people who are able to recall their dreams in vivid detail, and others who forget their dreams as soon as they wake up, there are startlingly few people capable of telling others about their dreams in a way that effectively conveys both the significance and weird wonder of it all. Strawberry Mansion is the dream that Birney and Audley debuted at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, hoping to capture audiences’ minds with its story of a tax auditor slipping into people’s subconsciouses. For all its ambition and interesting concepts, though, the film unfolds in fits and starts that make it tough to keep ahold of the tangled thread of a tale it’s trying to weave into something magical. There’s a lot going on in the movie, but by the end, it’s hard not to feel as if Strawberry Mansion doesn’t quite know what it wants to be.

[referenced id=”1669752″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2021/02/in-were-all-going-to-the-worlds-fair-the-void-does-more-than-stare-back/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/05/odliyzg3wo5fxnrd4xrt-e1612471422872-300×149.png” title=”In We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, the Void Does More Than Stare Back” excerpt=”If you’ve been following the coverage of this year’s all-digital Sundance film festival, there’s a very good chance that by the time you read this review, you’ll have already seen some version of the image above from Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair.”]

What little Strawberry Mansion tries to reveal to you about its protagonist James Preble (Audley) is just enough to beg a number of important questions about the movie’s larger world. Unfortunately, they go mostly unanswered. As an auditor working within the department of taxation that deals in people’s dreams, Preble’s more than accustomed to spending time mucking about in analogue recordings of the visions that come to people while they’re in REM sleep. The simplicity of his job — he goes to people’s homes and reviews tapes of their dreams while cataloging the taxes they should have paid for thinking about things like random birds and fast food — makes you wonder how and why the world came to be this way.

But instead of giving you enough context to appreciate the intimate strangeness of Strawberry Mansion’s story, it instead plays with the question of whether what you’re seeing is real or imagined to the point that the movie becomes nearly incomprehensible. As Preble sets out to pay a visit to Arabella Isadora (Penny Fuller), an elderly woman who’s spent years ignoring the IRS, the film attempts to introduce ideas that make it possible to see parallels between its reality and our own — especially the prevalence of targeted advertising.

Unsettling as the idea of dream-ads are, the apathetic, methodic quality Audley brings to his performance conveys the idea that nothing about this day in particular stands out to Preble before he arrives at Arabella’s cluttered home. Ads are just part of people’s lives to the point that the woman, in her desire for freedom, straps a device to her head before she goes to bed every night in order to block the intrusions. You’re left wondering whether Strawberry Mansion’s vision of the future of adblocking tech is widely adopted or if it’s something unique to Arabella that would draw the government’s attention. It’s small, but significant details like that repeatedly cause the movie to falter.

In Arabella’s dreams, she is depicted as both her present self and a younger version portrayed by Grace Glowicki as a kind of dream-like pixie who guides Preble through the corridors of her psyche in an effort to show him her emotional depths that others have long since assumed were gone because of her age. Arabella’s mind sharply contrasts with Preble’s, which you see in a handful of more nightmarish scenes where his thoughts are besieged by persistent, demanding calls to action for fried chicken and shutting the rest of the world out.

There are a number of moments where the movie’s plot falls apart, however, because the story frames Preble and Arabella as being on two ends of the spectrum in terms of how people cope with “normality” in this world. As Preble spends more and more time living within the realm of Arabella’s recorded dreams, they shape his perceptions of her in the real world. Again, you’re left wondering how, if the government’s watching everyone to this degree, she managed to get this far without anyone noticing.

Were Strawberry Mansion a simple two-hander about a pair of people coming to intimately know one another by sharing thoughts as full-body experiences, the movie’s messaging might be somewhat clearer. Instead, the main character arcs are muddled by unnecessary antagonists that come in the form of Arabella’s conniving family members Peter Bloom (Reed Birney) and Martha (Constance Schulman). Their presence ends up feeling like a distraction from Prebble and Arabella, whose characters could both stand with a bit more depth to make them the compelling figures the script wants them to be.

Strawberry Mansion isn’t exactly the most memorable movie about what comes to us as we sleep or what our relationships with taxation are like, but it’s certainly working with concepts worth mulling over should you give it a shot.

Strawberry Mansion debuted at Sundance 2021 and does not yet have a distributor.