Need to send a message to a friend 80 km away? Today, you’ve got plenty of options — whether it’s SMS, email, tweet, Facebook message, Zoom video chat, or the old-fashioned telephone. But back in the 1930s, the choices were much more limited. You could use the phone or write a letter or send a telegram. And that was almost it. Almost.

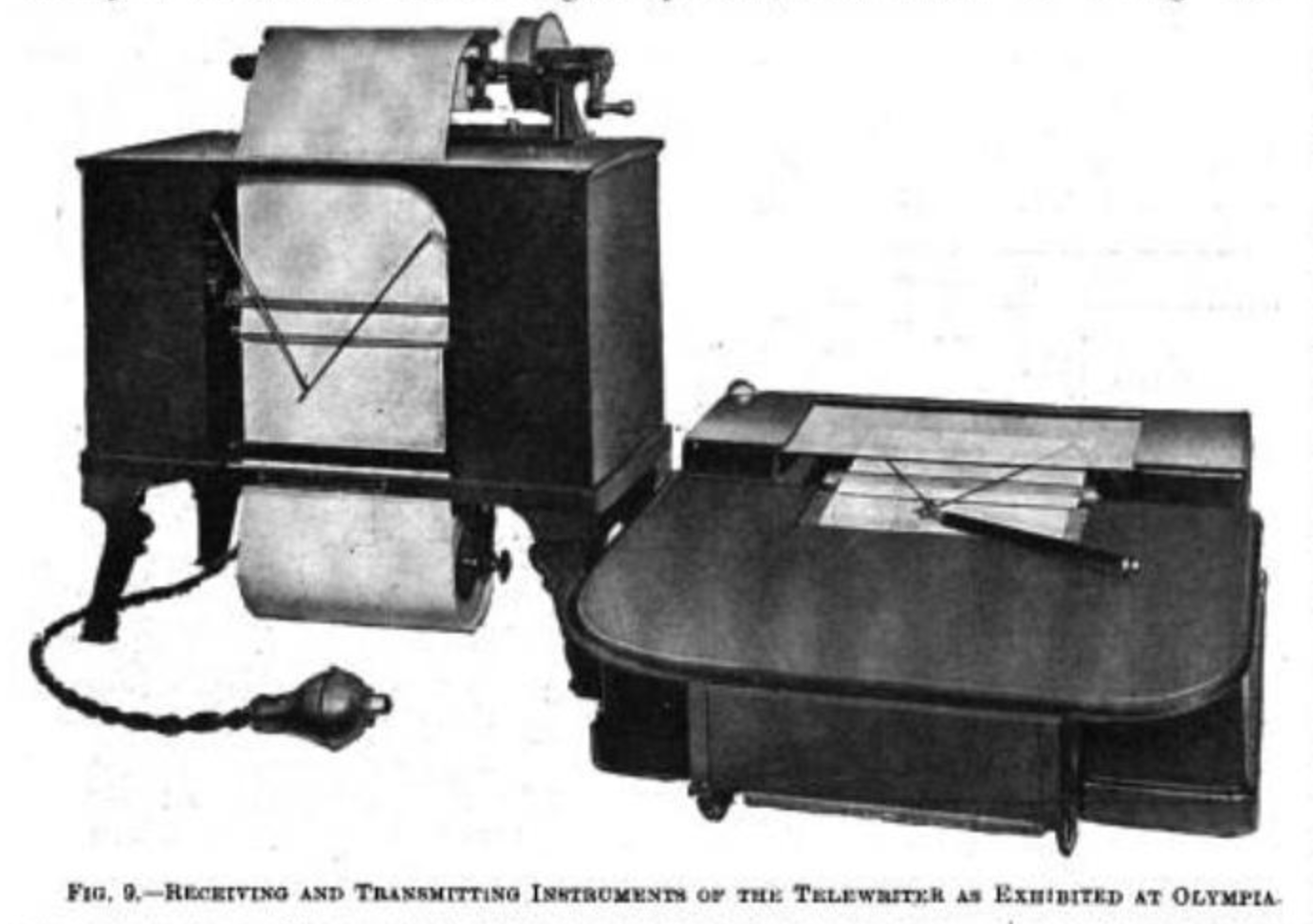

In the early 1900s, a new invention called the telewriter swept on the scene, allowing people to hand-write messages that could be electronically translated by a robotic arm at a destination up to 80 km away.

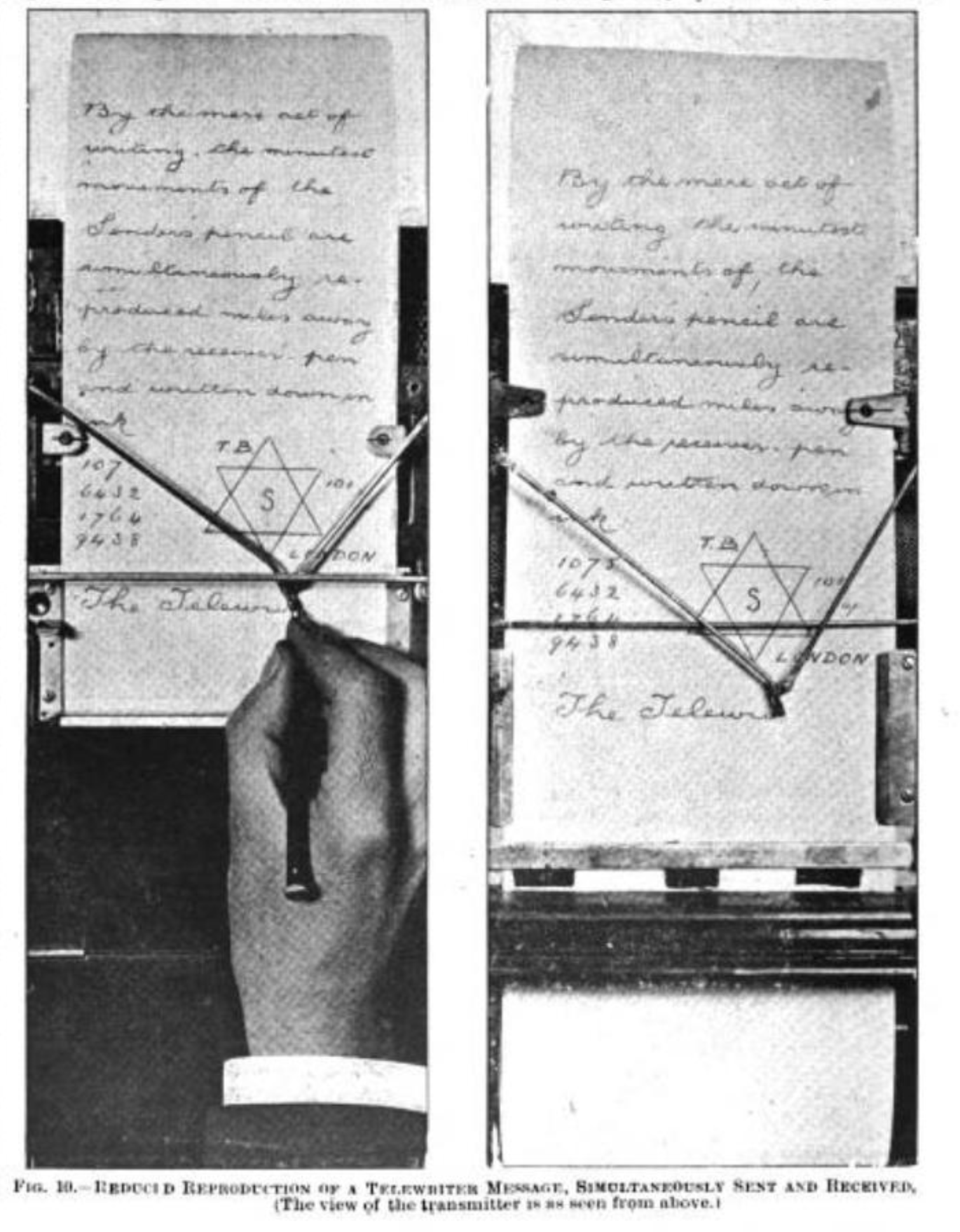

The user’s pen was connected to two swivelling arms, described in a 1910 issue of Popular Science as a pantograph, which calculated where exactly the pen was on the paper as the user wrote their message. Those positions were translated into electronic signals that would match an identical pen, controlled by similar swivelling arms at the end of the communications line, drawing out an exact copy of the user’s letters or drawings.

British Pathe has video on YouTube of the device in action during the 1930s.

The first mentions of the telewriter appeared in London in 1908 and every few years there’d be a new notice in newspapers and journals about how the invention was being improved.

The October 27, 1911 issue of the Mechanical Engineer magazine explained that the telephone would still prove useful for most conversations, but the telewriter allowed for both accuracy in communication and a written back-up of the conversation. The magazine also noted how useful it could be in places like factories, where it might be too noisy to carry on a verbal phone call.

From the Mechanical Engineer:

The telewriter does not supplant the telephone, but it will undoubtedly form an indispensable adjunct. As long as two people want to talk to one another the telephone will always be needed, but there are messages requiring accuracy in transmission that call for no personal conversation, but whose value is immeasurably added to by a written record duly signed by the sender, and it is in dealing with such messages that the telewriter proves itself invaluable.

The receiving instrument being entirely automatic, one operator — the sender — can transmit a message in the absence of the addressee, who, on his return, finds it written in ink, and in the handwriting of the sender. The instrument is unaffected by noise, and thus may with advantage be used in factories, shipyards [etc.] or wherever machinery is at work, and again, the wire cannot be tapped so as to intercept messages.

The UK’s Pitman’s Journal wrote in 1912 wrote about how three daily newspapers were using the telewriter from a room behind the press gallery at the House of Commons to submit fast-breaking news to the ink-stained wretches on Fleet Street. The message had to be routed through London’s Central Telegraph Office.

From Pitman’s Journal on March 2, 1912:

The possessor of a telewriter may ring up the telewriter exchange which is connected with the Central Telegraph Office (G.P.O.), and simply write the telegram on the transmitter. It is an ingenious instrument which makes the telephone write, and it is used in hotels, offices, workshops, counting-houses, and shipyards. It is now undergoing Admiralty at Portsmouth with a view to its being installed on H.M. ships.

The obvious benefit of this system was that it didn’t require typing skills to quickly write down a message and get it sent. Newspapers of the early 20th century imagined that the telewriter would be installed in phone booths, where people could write their messages by hand. The messages would then be transmitted to the Post Office where they would be forwarded to the intended recipient.

The telewriter was highly advanced for the 20th century, but a more rudimentary version of the device was actually invented in the early 19th century. It was called the Polygraph (not to be confused with the polygraph test, invented in 1921), a handwriting duplication machine invented by John Isaac Hawkins and Charles Wilson Peale. The invention allowed people to write one letter and instantly have a copy of that same letter to store for their personal files. The letter still needed to be sent by old fashioned postal workers, of course, but the idea cut the time needed to make a duplicate in half.

U.S. president Thomas Jefferson was so impressed with the device that he bought several and had them in his home and at the White House, which was known at the time as simply the President’s House. Jefferson described the invention as “the finest invention of the present age,” according to the scholars at Monticello. And, much like tech nerds might clamor for the latest and greatest gadgets here in 2020, Jefferson was excited whenever there was an improvement on the Polygraph.

“He was always waiting for the latest one,” Charles Morrill, historian and craftsman at Jefferson’s Monicello says in a video from 2018. “Much the way people might wait for the latest iPhone or computer today. I’ve been able to document ten machines that he owned over the years.”

By the 1920s, it had become possible to transmit photos across the Atlantic Ocean for reproduction in newspapers the very same day. And during the 1930s and ‘40s, newspaper publishers were experimenting with sending papers via wireless fax directly into the homes of readers in Miami, Florida.

The 20th century saw the rapid rise of visual media, thanks in no small part to the popularization of movies, TV, and glossy full-colour magazines. But it’s the less-remembered inventions that we love so much here at Gizmodo. The telewriter may not have seen widespread adoption, just as the faxpaper was a passing fad, but it has a special place in our heart for its ingenuity.

Today, there are plenty of ways to use your handwriting on tablets and touchscreens of all kinds, sending messages halfway around the world. But typed words via keyboard really seem to have won the day for most practical uses at work and in the home. And that’s ok with us. Because our handwriting has really gone to shit.