A bombshell study from last month made the extraordinary claim of finding a type of molecule on Venus associated with life. An independent re-evaluation of the methods used in the paper has reached an entirely different conclusion, finding “no statistical evidence” for the biomarker.

We knew it would only be a matter of time before other researchers weighed in.

Life on Venus? Seriously? This scorched planet — in which surface temperatures exceed 450 degrees Celsius — might actually be habitable?

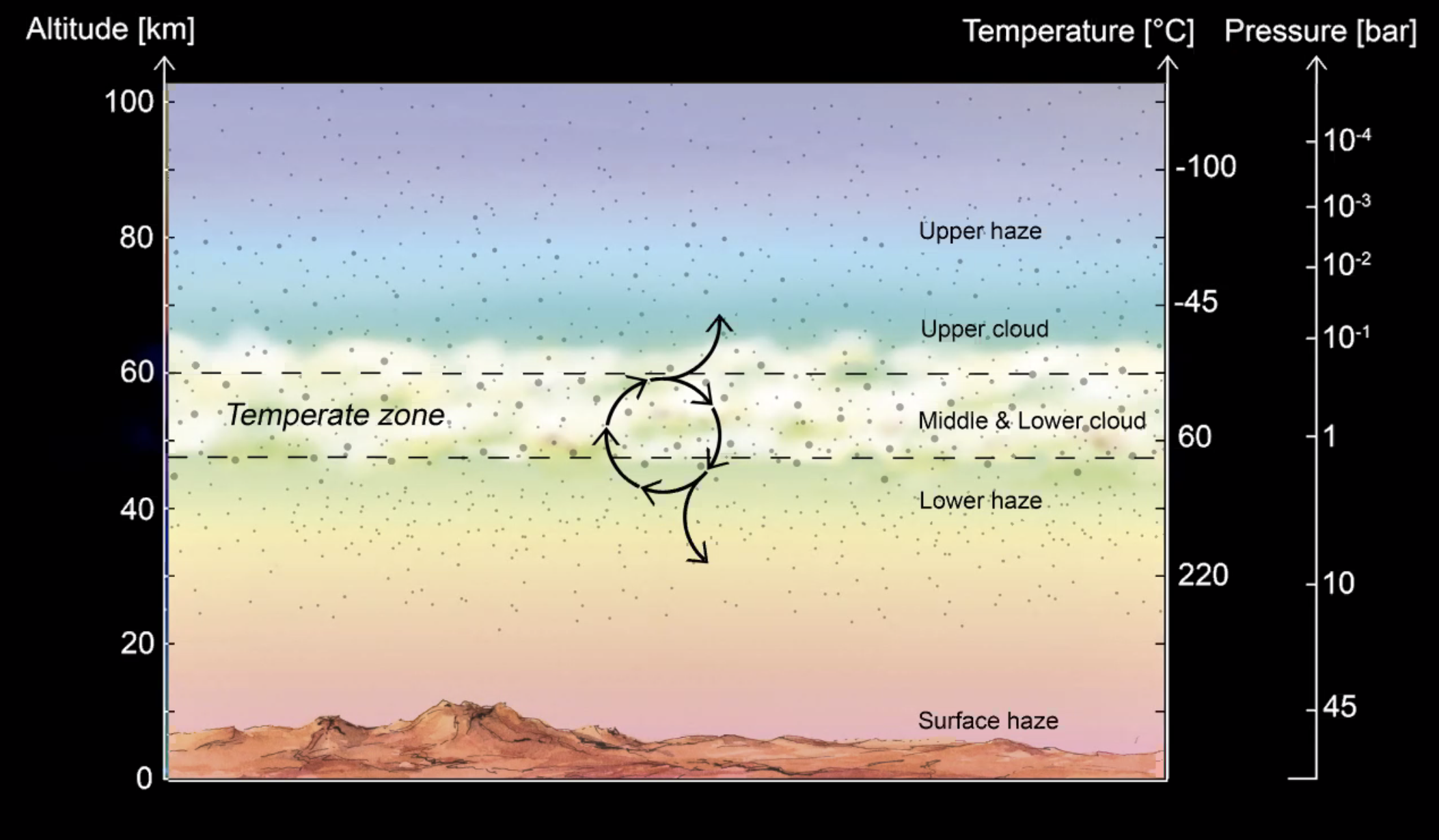

It seemed impossible, yet it was presented as a possible explanation for a provocative spectral signal reported this past September. A research team led by astronomer Jane Greaves from Cardiff University claimed to have detected phosphine on Venus, a gas that, on Earth, can only be produced by microscopic organisms, at least as far as we know. To be clear, the researchers never made an explicit claim for life on Venus — they simply noted that it could be one explanation for the presence of phosphine. Quite suddenly, we found ourselves envisioning bacteria-like creatures, with their stinky phosphine-filled farts, floating in the cloud layers of the Venusian temperate zone.

This vision, however, may be pure fantasy, according to new research led by Ignas Snellen from Leiden University. His team’s new paper, still in pre-print form and requiring the scrutiny of peer reviewers, takes exception to the claim, concluding there’s “no statistical evidence” for phosphine on Venus.

We were kind of expecting this. As Carl Sagan used to say, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” The evidence presented in the Greaves paper is neither extraordinary or ordinary, according to the Dutch researchers — it’s just entirely unreliable.

The Greaves paper, published to Nature Astronomy, used data gathered by the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimeter Array (ALMA) based in northern Chile. Snellen and his colleagues took a look at the same data, which was given to them by the original research team (the authors actually thank the Greaves team in the acknowledgements section, because scientists are respectful that way). They applied the exact same methodological approach when re-analysing the possible phosphine signal, which showed up along a lone spectrographic line at 267 GHz. Try as they might, the Dutch team could not verify the results reported in the previous Nature Astronomy paper.

Writing in their study, Snellen and his co-authors said the procedure used by the Greaves team to study the spectral data was “incorrect,” resulting in a “spurious” high signal-to-noise ratio.

Indeed, astronomers are constantly having to grapple with signal-to-noise issues with their data, in which they must tease out the wanted from the unwanted. Space is filled with all sorts of extraneous stuff that can mess up spectrometers, including stray photons and electrical bursts. Astronomical data can also get clouded by more local sources, such as microwave ovens (yes, seriously). Here, the Greaves team claimed to be in possession of far more good data than bad (i.e. a high signal-to-noise ratio), a claim the Snellen team disagrees with. Rather, the signal-to-noise ratio of the proposed phosphine signal is actually quite low, they argue, and in fact, it’s too low to be meaningful.

[referenced id=”867167″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2015/04/mysterious-radio-signals-came-from-microwave-oven-not-outer-space/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/13/a0rxue2p1uxhfkxtc03i-300×167.jpg” title=”Mysterious Radio Signals Came From Microwave Oven, Not Outer Space” excerpt=”Sometimes, the powerful radio bursts detected by our telescopes have the look of alien beacons. Other times, they’re caused by scientists reheating coffee.”]

“In astronomy, features at such a low [signal-to-noise ratio] are generally not deemed statistically significant,” the authors write, adding that features observed at such low levels “have no statistical meaning,” as it makes “any link to a false positive probability unreliable.”

So basically, Snellen and his colleagues are claiming that the Greaves team made some mis-measurements and miscalculations, leading to an unfounded conclusion. What’s more, their analysis “shows that at least a handful of spurious features can be obtained with their method,” leaving them with no choice but to conclude that the Greaves study “does not provide a solid basis to infer the presence of [phosphine] in the Venus atmosphere.”

Ouch.

Well, that’s science for you. This is a good thing, however: Scientific progress relies on scientists being able to duplicate and verify the work of others (or in this case, not — but it should still be considered progress, as it moves the conversation forward).

This story is undoubtedly not over, as the original team, and possibly other scientists, may have a thing or two to say about the claims being made in the Snellen paper. And indeed, the new paper itself has yet to go through peer review, which means these new claims must now stand the scrutiny of others.