If you were on trial for a murder you didn’t commit, it’s possible that Facebook has evidence that could set you free. But it is extraordinarily unlikely that Facebook would hand it over. Facebook would not only refuse to help you, but it will pay exorbitant legal fees to fight your subpoenas through appeals courts as you languish in jail for years. It will ignore your attorneys and judges. It will do so in the name of protecting your privacy. And based on the current law, Facebook’s not entirely wrong to hang you out to dry while it gives law enforcement all the information it desires.

Facebook is operating under an arcane 1986 data privacy law known as the Stored Communications Act (SCA). It’s an ostensibly good policy designed to protect citizens’ Fourth Amendment right to decline unlawful search and seizures in their own homes by extending those protections to their digital homes and prohibiting service providers from sharing users’ “electronic communications” without their consent. But the SCA baked in exceptions for “governmental entities” with search warrants and subpoenas, which opens the door to cops, but not defence attorneys, hobbling the latter’s access to evidence even with court-ordered subpoenas.

That disparity is escalating into a five-alarm-fire, as Google processes so many search warrants from law enforcement that it has monetized them, the FBI perennially pushes companies for even more liberal access to your stuff, and the Attorney General crusades to strip end-to-end encryption.

Plus, the law’s rusty and nonspecific language, authored at a time when the word “inbox” primarily referred to a paper bin on a wooden desktop, could never have anticipated how privacy might apply to a since-deleted Facebook post that was initially available to the public, or the unfathomable scope of new information at law enforcement’s disposal.

In the latest case to highlight this problematic imbalance, Iraqi refugee Omar Ameen is facing potential extradition from the US for the alleged ISIS-related murder of an Iraqi police officer. Ameen’s defence attorneys have frantically attempted to obtain Twitter and Facebook posts which appear to show a group of men taking credit for the murder on behalf of the Mujahideen. The defence has obtained an anonymously submitted, undated printout of the posts from Iraqi court documents, but Twitter and Facebook won’t provide the originals.

Are Facebook and Twitter correct in following the letter of the law, a law designed to protect citizens’ privacy, even if that privacy possibly belongs to members of ISIS, and even if protecting it comes at the expense of a man’s life? Should since-deleted public posts, which could just as easily have been preserved forever by the Wayback Machine, really fall under privacy protection? And, U.S. federal law aside, the particulars of this extradition case”which the New Yorker’s Ben Taub credibly portrays as a product of Trump-era Islamophobia”have an ethical obligation to help its users escape persecution?

The law

At the moment, global data privacy is governed by brief statutes that are about as applicable as 18th-century road regulations would be for modern highways. Early descriptions of the act in the U.S. often contextualise it as a logical extension of Fourth Amendment privacy rights afforded us in our physical “homes.” As cybercrime scholar Orin Kerr explained in a paper published in 2004, just a few months after the invention of Facebook, 1986 lawmakers were beginning to understand that the internet doesn’t actually parallel the boxes in which we live guarded by our own physical locks and keys; in the years leading up to the SCA, for example, the Supreme Court had upheld that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to “information revealed to third parties,” implying that our privacy might not apply to data we send to ISPs. For that and similar Fourth Amendment loopholes around third parties, “Congress has tried to fill this possible gap with the SCA.”

But when U.S. Congress tried to fill that gap, they were faced with protecting a few specific types of documents, rather than governing a new world without hardcopy analogies. As Ryan Ward pointed out in 2011 in the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, when the Stored Communications Act was passed in 1986, internet users were only able to do three things: download and send email, post on bulletin boards, and upload and store information. The SCA only anticipated those three functions.

High-ranking officials might have emailed U.S. government secrets in 1986, like letters or memos that you could print out and shred. But you couldn’t fire off a tweet of your dick and delete it only after the media caught wind; an ad tech company couldn’t have used your personal device to track your every move; criminals couldn’t post timestamped and location-tagged photos of themselves committing crimes; there simply wasn’t a massive self-surveillance apparatus begging to be fed by billions of people for whom feeding the machine is a borderline addiction. The 2020 web is more expansive and unruly than previously imaginable, and privacy is a core problem.

“Privacy rights are a serious concern,” UC Berkeley School of Law attorney Megan Graham told Gizmodo. “But so is the right to a fair trial. My guess is that in 1986, nobody was thinking about the fact that criminal defendants would need [digitally transmitted] information to build their defence.”

The SCA was aware that emergencies would arise, and allowed service providers to voluntarily disclose information that involves “danger of death or serious physical injury” to “governmental entities.” If they stumbled upon what looks to be evidence of a crime, they could share that with “law enforcement.” And the SCA dimly anticipated new avenues for kidnapping and distribution of child pornography, crimes for which tech companies were allowed to contact the U.S. National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children. (It extends the same voluntary disclosure options for intended recipients of the message, an employee entrusted to forward the message, and in cases where disclosure is necessary for rendering services.)

But as the authors make painstakingly clear, they anticipated criminal investigations, requiring companies to comply with search warrants and subpoenas from “governmental entities,” which the SCA defines strictly as “departments or agencies” of the United States. But while one might think that “governmental entities” would cover court-ordered subpoenas from the defence, Graham said, “courts are not generally considered to be agencies of the United States.”

“The statute is an endless warren of definitions,” she said.

The refugee and the ISIS post

The case against Ameen is riddled with holes: A recent revelation that the U.S. Department of Justice has long held onto phone records that could prove Ameen’s innocence; an inconsistent teenage eyewitness who’d never met Ameen; an Iraq-based FBI informant with a personal vendetta; a statement in Ameen’s favour from the victim’s widow; botched Iraqi court documents; a lengthy national security vetting process that allowed Ameen into the country in the first place; a Department of Justice that’s operating under a Presidential Administration which has indicated on numerous occasions that it’s out to find terrorists in the refugee pool.

At the time of the murder, Taub writes, Ameen’s passport was “in Turkish possession” as he waited in Turkey through the United Nation’s refugee resettlement process.

Ameen underwent this multi-year process in order to avoid being kidnapped and murdered for his cousin’s Al Qaeda affiliation, which piqued the interest of the FBI, whose main corroborator was reportedly an unstable teen who’d never met Ameen but identified him from a Facebook photo. Taub characterises potential extradition as “almost certain death,” with his report ending on a quote from an Iraq-based U.S. military informant who promises: “I will execute him.”

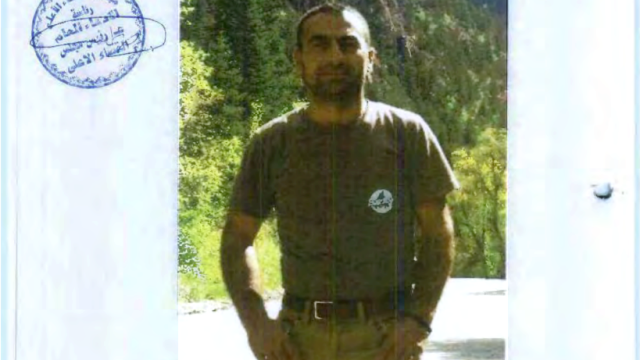

The potentially exculpatory Facebook post in question comes from an undated printout of an image shared on Facebook and Twitter that was anonymously submitted to the Iraqi court. (The unredacted image below was provided to Gizmodo by one of Ameen’s defence attorneys.)

The image shows what appears to be a group of boys (none of whom resemble Ameen) holding guns and claiming that the Mujahideen had committed the murder. Authorities translated the caption in an Iraqi court document as: “Today is the day to eliminate some rotten heads. Now in Rawah, the criminal Ihsan Al-Hafiz has been eliminated at the hands of the Mujahidin.” The Facebook account that appears to have posted the image still exists and according to Ameen’s defence is linked to the support of ISIS.

The post might not save Ameen, since, as the New Yorker also points out, extradition proceedings carry an extraordinary burden of proof, namely that the defence must “obliterate” the credibility of the accusations rather than prove reasonable doubt. While a post showing other people taking credit for the murder stacks up with a good deal of other testaments to Ameen’s innocence, it’s unclear that the post would “obliterate” the accusations.

Currently, the defence is pursuing a more concrete piece of evidence, cell phone records that Ameen’s attorneys say would prove that he was in Turkey at the time of the murder. In a recent hearing, the judge delayed certifying extradition after a revelation that the Turkish cell phone company had sent a letter to the State Department eight months ago agreeing to share them. The State Department then forwarded that letter to the only entity that can present those records in court”the Department of Justice, which sat on it.

The case has raised numerous issues that have been bubbling in American governance over the last several years. It’s also given us a tangible example of a moment when a defendant was issued a blanket denial for evidence that a prosecutor could easily get their hands on as long as they form the right argument.

The platforms

Ameen’s attorneys went to Facebook and Twitter with court-approved subpoenas for deleted posts and data from accounts on each social network (both under the same handle); the companies provided non-content information for the alleged murderers’ accounts (IP addresses, emails, etc.) but refused to provide the actual posts, arguing that they’re prohibited to do so under the SCA. (As further evidence of outdated privacy policy, UC Berkeley School of Law attorney Megan Graham explains that the right to “non-content” data is modelled on an 1878 case involving the right to inspect the exterior of a piece of mail; you’ve openly disclosed the stuff you write on the outside of the envelope to the post office. The SCA does not cover non-content information such as metadata, location, and login information. This loophole has also led to criticism. No one said there are any easy answers for crafting effective privacy policy.)

“I have no reason to think they don’t have the content,” one of Ameen’s attorneys, Rachelle Barbour, told Gizmodo. “They never said they don’t have it, just that they weren’t going to give it to us.”

A Twitter representative directed Gizmodo to the site’s Legal Requests FAQs, which states that Twitter notifies users of legal requests and makes “exceptions” to this policy in “exigent circumstances, such as emergencies regarding imminent threats to life, child sexual exploitation, or terrorism.”

Gizmodo asked whether the post displaying men with guns possibly claiming to have committed murder falls under the terrorism exemption but we did not hear back.

Even more tragically for Ameen, Barbour claims that Facebook told the defence that it had also not retained Ameen’s detailed IP information prior to July 28, 2014, which could have placed his location in Turkey at the time of the June 22, 2014, murder. In a declaration, Barbour quoted Facebook’s counsel as saying that “there is a rolling log of IP addresses associated with an account, but that log only retains a limited amount of IP addresses associated with the account.” Facebook was able to provide evidence that Ameen had liked a post on the date of the murder, while, as Ben Taub notes, there was no internet service in the area where the murder took place.

Both Facebook and Twitter declined to address Ameen’s case directly but stated to Gizmodo that as a policy they generally follow SCA guidelines.

Tech companies does not like the present administration’s ethical void; Facebook, in practice, follows the letter of the law, which means honouring a lot more requests from law enforcement than from defendants on trial for murder.

Just last year, Facebook claims to have “provided some data” in about 88 per cent of over 50,000 government requests, according to Facebook, a number which has hit an all-time high in 2019, also according to Facebook.

And despite Facebook’s attentiveness to government requests, Barbour says, typically companies ignore defence subpoenas altogether.

“The companies respond this way [to subpoenas] because they fear being sued, they market themselves to customers as guaranteeing some level of privacy,” Pace University professor of law David Dorfman told Gizmodo. “And, in general, there’s a movement afoot in the tech world asserting maximum cybersecurity.” It just so happens that defence attorneys’ access to data is one of the areas in which tech companies have legal leeway to tighten their policies when it comes to what they’ll share.

Both Facebook and Twitter declined to comment on the length of time they store deleted posts or posts from suspended or deleted accounts, but Facebook’s data retention policy states that Facebook stores data (including photos) “until it is no longer necessary to provide our services and Facebook Products, or until your account is deleted”; it does not state that it deletes posts after they’re taken down, but only after you delete your whole account. (And even after account deletion, cleaning servers takes time.) Twitter claims to delete data from deactivated accounts after a brief timeframe, though recent reports point to the contrary.

Serving subpoenas to the void

“What’s going on here with the SCA is unusual,” UC Berkeley School of Law assistant professor Rebecca Wexler told Gizmodo. “This is a statute that just blocks subpoena power entirely for a whole bunch of information, regardless of how substantively sensitive it is.” Wexler points out that, under the current “adversarial system,” law enforcement must hand over evidence that exonerates the defendant if it happens to find it, but it has no obligation to investigate on behalf of criminal defendants. Because that duty rests solely on defence attorneys, the defence’s statutory subpoena powers reach a lot of sensitive information”as a result of which, the system has put safeguards in place to mitigate harassment or abuse. The SCA hasn’t caught up to implementing the checks and balances which still allow a defence attorney to do her job, she said, and prosecutors are using this as both “a sword and a shield,” gathering evidence in their favour while the statute bars the defence from accessing the same sources of evidence.

Others see this as a straightforward extension of the adversarial system, in which law enforcement is expected to be able to access more information than the defence via search warrants. The San Francisco Chronicle quotes UC Berkeley law professor Orin Kerr, who calls the companies’ resistance “a new version of an old problem.”

“Imagine the government charges Alan with murder,” he told the Chronicle. “Alan wants to argue that Bob committed the crime instead. Would we let Alan break into Bob’s house and search for evidence of Bob’s guilt?”

As Pace University professor of law David Dorfman explained to Gizmodo, the defence couldn’t use a subpoena based on mere relevance to obtain that evidence, either; it could only be seized by a government entity pursuant to a search warrant based on probable cause. “Even more so if the document sought would tend to incriminate the person who had it, they would rely on the 4th Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure as well as the 5th Amendment right against compelled self-incrimination,” he added.

Marc Zwillinger, founder of ZwillGen, which provides legal advice for tech companies, extended that line of thinking in an email. “Where the constitution requires a warrant to enter a home, defence counsel can’t use that authority… although they can subpoena documents in the home. Is that the right or wrong answer for stored communications? Congress should consider it.”

Zwillinger didn’t cast blame on the social media companies themselves. “I don’t think it says much about the attitudes of tech companies to defence subpoenas,” he wrote. “Rather, it speaks to what the SCA allows and doesn’t allow. There is no mechanism under the SCA for defendants to gain access to private content without subscriber consent. The SCA is pretty clear on this”yet subpoenas keep coming. Until a court rules the SCA to be unconstitutional or the SCA is amended, providers are right to resist them.”

Or courts could simply interpret the SCA differently. “I think the SCA could be read to include an implied exception for criminal defence subpoenas,” Wexler argued. “Even if a court is in a jurisdiction with bad precedent on this issue, they can instruct the jury on what’s called an adverse inference. They can tell the jury that the defendant tried to get access to evidence and were not able to access it, and therefore, you must presume that the evidence would have been favourable to them. That’s fully within the power of the courts today all over the country.” Congress could also amend the statute, of course.

What about pleading the 4th, 5th, and 6th?

In a separate, long-drawn-out murder case, Facebook and Twitter’s SCA stance has worn down the patience of judges and defence attorneys. Derrick Hunter and Lee Sullivan, who were accused of involvement in a 2013 drive-by shooting, waited in prison for six years while attempting to get critical evidence from the companies before beginning their trials.

While the shooter (Hunter’s brother) has confessed, Hunter and Sullivan maintain that Sullivan’s ex-girlfriend, who had rented the car, lied to police telling them that all three had driven her home prior to the shooting. Hunter and Sullivan’s defence, who pointed out that the ex gave the police various stories, alleged that she had tweeted threats against women Sullivan was involved with. In order to deny her credibility, they pulled up a 2012 tweet, stating, “BIIIITCH I WILL COME 2YA FRONT DOOR,” and issued wide-ranging subpoenas against Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter for “any and all public and private content” related to her accounts with no time limits. Sullivan also served subpoenas to Facebook and Instagram for “any and all public and private content” from the victim’s accounts, which included gang-related threats. In the same trial, an investigator testified that the police had used Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter records to build their own case against the defendants.

Facebook and Twitter moved to quash the subpoenas and dragged it out through a years-long appeals process. The defence argued that the Fourth Amendment right to privacy doesn’t cover posts that were once public, and that Twitter and Facebook were blocking defence attorneys’ Sixth Amendment duty to investigate and provide exonerating evidence. In the case of the victim’s records, they argued that the deceased can not assert their Fifth Amendment rights preventing self-incrimination.

Facebook and Twitter suggested (via attorneys from the same law firm) that the defendants try to obtain consent (from a dead person and the person who rented the car) or that they work with the prosecution to obtain a search warrant (which is not going to happen because prosecutors aren’t generally fans of undermining their own case).

The case finally arrived in 2018 at the California Supreme Court, which sided with the defence in finding that public posting constitutes lawful consent and then kicked the case back to the trial court to decide whether the requested posts were “private” communications. In 2019, a Superior Court judge extended the right to cover private communications and held Facebook and Twitter in contempt of court, writing that the companies “appear to be using their immense resources to manipulate the judicial system in a manner that deprives two indigent young men facing life sentences of their constitutional right to defend themselves.”

As Hunter and Sullivan sat our their sixth year in jail, the judge didn’t take much interest in Facebook or Twitter’s civil liberties stance. “I don’t think it will be any consolation to the defendants and their lawyers that you think you are vindicating federal rights,” he reportedly told Facebook and Twitter’s attorney. But all the judge could do was fine the companies the maximum penalty of $US1,000 ($1,495) each. And then Facebook and Twitter went home. (Hunter and Sullivan invoked their rights to a speedy trial. Hunter’s case was declared a mistrial in January; Sullivan will be sentenced on February 25th.)

Unlike Ameen’s case, in which defence attorneys are seeking a few previously selected posts, the subpoenas here are broad enough to raise the question of whether anybody on trial should be allowed to point to a guy over there and demand all of his stuff. The solution the judge presented was that he would review the posts on camera (privately) and then pass along any content he deemed relevant to the defence.

As Megan Graham pointed out, the same exceptions have been made for psychiatric and health records, which can be obtained in extenuating circumstances with a court order and privately reviewed by a judge. “That’s not to say defendants should get what they want in all circumstances, but we know how to put restrictions in place in other types of cases,” Graham said.

Vulnerabilities require updates

Law enforcement operates much closer to the people who make the laws in the first place, and the laws reflect that”or, in Rebecca Wexler’s words, “worsen the imbalance.”

“The Stored Communications Act is a byproduct of the legislative process,” Wexler said. “Law enforcement has a powerful lobby seeking exceptions to privacy laws, but few people lobby on behalf of criminal defendants for parallel exceptions.”

“Every indication in the legislative history shows that this was an accident,” she added. “It’s the product of oversight, not of reason.”

As legislation is finally catching up to new types of data, the SCA’s problem is spilling out to new privacy laws. The SCA doesn’t cover metadata, but the CCPA does”and, as Wexler points out, it and dozens of proposed bills incidentally contain the same workaround for prosecutors but not defence attorneys.

U.S. federal privacy law is coming. There’s time to write it correctly. But by the time it’s retroactively fixed, it’ll be teetering towards obsolescence.