Although attempts have been made, today marks the first official animated stories told in the Star Trek universe since the days of the charmingly goofy Star Trek: The Animated Series in the early ‘70s. While they might not be the particularly traditional Trek tales you’d expect, they offer a promise that this medium can push Star Trek to interesting new places.

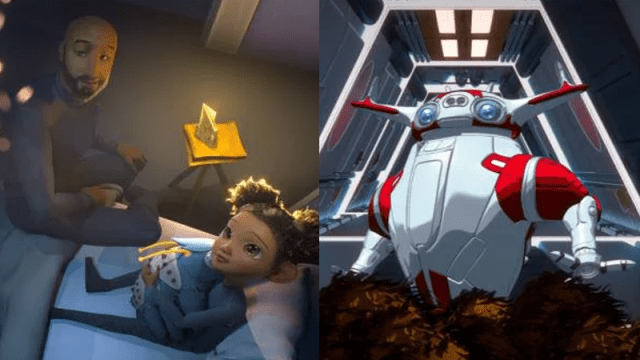

Today two brand new Short Treks were released—“The Girl Who Made the Stars,” by Brandon Schultz and Olatunde Osunsamni, and “Ephraim and Dot,” by Chris Silvestri, Anthony Maranville, Michael Giacchino, and they couldn’t be further apart from each other in terms of tone.

On the surface, at first, it seems the only thing that really connects the shorts is that they’re both animated. But for all the ways they both push what can be considered as Star Trek stories, beneath the esoteric frames and charming animation beat hearts that ring true to themes the franchise has held deep in its chest since the very beginning.

[referenced url=” thumb=” title=” excerpt=”]

“The Girl Who Made the Stars” is the more esoteric of the two. Framed as a story told to a young Michael Burnham (Kyrie McAlpin) by her father Mike (the returning Kenric Green, reprising his role for Discovery’s second season) while she’s struggling to get to sleep one night. The tale told here is actually an extrapolated version of one the adult Michael tells the audience in the opening of Discovery’s season two premiere, “Brother.” It describes a mythical folk tale of a young girl from an African tribe bringing the light of the stars to her people so that they may travel to new, fertile lands to survive. It’s a poignant and beautifully told story, highlighting animation as a medium to tell a story that is heavily stylised in a way you might not expect Star Trek to frame a narrative like this.

But for all its esoteric imagery on the surface, the tale told in the short is one that fundamentally speaks to the values which have guided Star Trek since the very beginning. The tale of the titular girl—who is essentially the young Michael recast in the story, inserting herself into the protagonist’s footsteps—is one of ignoring a fear of the unknown to satisfy an intellectual curiosity her elders have left unsupported.

It’s a story about the pursuit of knowledge and understanding: the girl wants to know what the lands only reachable by travelling through the night are like, and she wants to know if her people can survive the crisis of over-farming their lands brought by a fear of moving beyond places reachable in less than a day’s travel. When she encounters an ethereal, alien being, the one who supposedly gives her the ability to chart the stars in the sky and act as a beacon safeguarding the girl and her people from the beasts lurking in the night, it becomes a story about communicating with new cultures and how cooperation can lead to hopeful new eras for all involved.

It’s a beautiful tale in its simplicity because that simplicity lets these values come through clearly. “The Girl Who Made the Stars” frames Star Trek’s boldest morals as ones that have defined humanity across generations, whether it’s values being passed from Mike to Michael, to the young girl and her elders, or across eons of time, from the ancient past to the boldly-goings-on of the future. It’s especially important as it’s a message told through, in a rare moment, “ancient” stories from a lens beyond the Western canon Trek typically relies on for its heroes’ view of history.

[referenced url=” thumb=” title=” excerpt=”]

How many times have we seen the series refer to the likes of Shakespeare and 19th century literature as almost the de facto when it comes to an interpretation of human history—even alien histories—on the show? There have been attempts before, of course. Chakotay’s trope-laden Native heritage on Voyager may have been handled clumsily, but it was at least an attempt to portray the cultural history of a person of colour in a way Trek hadn’t really tried before. That it’s taken so long for Trek to start doing this more regularly is unfortunate, but hopefully stories like this are only just the beginning.

“Ephraim and Dot,” meanwhile, strikes a decidedly different tone, not just visually (with a candy-coated colour palette evocative of the original Trek and its own animated counterpart) but in that it is, for all intents and purposes, a comedic riff on Saturday morning cartoons.

Complete with a schmaltzy narrator and retro opening titles, this short’s titular characters spend almost the entire runtime at each other’s throats in a Daffy Duck/Elmer Fudd, Tom/Jerry sort of comedically hostile relationship. Ephraim is a Tardigrade mother who doesn’t realise what madness lies ahead when she decides to nest her eggs aboard the Enterprise in the middle of its bonkers five-year mission, and Dot is an Enterprise repair drone (like those seen in Discovery) who sees Ephraim as a hostile being attempting to infiltrate the ship. There’s hijinks, there’s corridor chasing, there’s comical slapstick violence that might make a more traditionally-minded Trek fan bristle.

There’s also so much nostalgia on play, as the original Star Trek plays out in the background of Ephraim and Dot’s wild pursuit of each other. Deftly using moments and even recorded lines of dialogue from out of the original show, from “Space Seed” to “The Doomsday Machine,” and even beyond into moments like the fight with the Reliant in Wrath of Khan or its destruction in The Search for Spock. It’s like flipping through the entirety of the first Star Trek in flipbook format, decades of stories condensed to the background of a less-than-10-minute-long caper about a drone and a mycelial-warping space bug.

It’s spectacularly silly. It is unabashedly cartoonish. But it comes from a position of great love and reverence for Star Trek history and not just for its nostalgic use of scenes and dialogue. Star Trek arguably has a bit of a problem leaning on this nostalgia for the yesteryear a little too much recently, but at least here it’s a clever use of animation as a timeless medium to call back to a past that, in live action, would at this point require recasting á la Anson Mount and Ethan Peck on Discovery or “Trials and Tribble-ations” levels of archival footage trickery.

But because, ultimately, Ephraim and Dot’s story is, just like “Girl Who Made the Stars,” really about a timeless Star Trek tale: two radically different beings, unable at first to communicate effectively with each other, coming to a position of unity and mutual understanding, in spite of their great differences. It’s just that, instead of it being a Starfleet officer and an alien species, it’s a space water bug and a goofy robot programmed to do one basic thing: don’t let anything weird get on its ship.

Just as the Girl and the Alien in “Girl Who Made the Stars” manage to transcend barriers of being and culture to help each other out, Dot eventually comes to understand Ephraim’s plight—the Tardigrade isn’t a hostile invasive threat, but just wants to see its children safe, especially with every bonkers thing the Enterprise goes through in its hectic adventures. By the time it’s destroyed over Genesis in The Search for Spock, Dot decides to save the eggs from a similarly explosive fate, losing parts of its own body and, in the death of the Enterprise, its own reason for being, to protect the Tardigrade’s children so they can safely hatch and return to their parent. It’s simple, yes, and it told in an over-the-top silly style, but it is still fundamentally a Star Trek story that beautifully speaks to the franchise’s themes.

These two tales, on their own, may not be the grandest Star Trek stories ever told—but they don’t have to be. They prove there is space for Star Trek, on the precipice on an unprecedented level of saturation, to tell tales which are both reflective of nostalgic charms and push the boundaries of how the core themes of wanderlust, understanding, and exploration that define Star Trek’s heart can move into styles of storytelling that play with fantasy and comedy as much as they do science fiction and serious character drama.

[referenced url=” thumb=” title=” excerpt=”]

Above all though, they prove that it can do so in a medium the series has not really had the chance to deeply explore. Even if these two particular entries are little more than charming, simple tales—yet still reflective of some lofty ethical values—that promise in and of itself is very exciting indeed.