When Marshall Cordell started buying human bones in the late 1970s, he says a full skeleton from India cost “probably $US199″ Back then, almost all real human skeletons came from India, and companies there sent him catalogues listing everything from skulls to finger bones for sale.

“They were literally like an auto parts shop, only with real skeletons,” Cordell, who turned 71 this year, says today. “You could buy ear bones. You could buy human teeth.”

As the new owner of a medical chart company, the young college graduate with no background in medicine was entering the strange world of anatomical model sales. In the end, he would not only dominate the American fake skeleton market but change how we celebrate Halloween. He would become, in his own words, “the skeleton king of the world.”

In the 1990s, anatomical models sold by Cordell would appear in movies as casino decorations, and even on the back cover of a (later censored) Nirvana album. But in the beginning, he was just trying to grow the company he bought with $US5,000 ($7,051) he borrowed from his dad.

“I was figuring out a way to expand the business beyond anatomical charts,” says Cordell, who saw potential in selling discounted skeletons by buying his bones direct.

The rise of plastic bones

Doctors and scientists were looking for easy access to skeletons long before Cordell entered the bone game. In 1543, father of anatomy Andreas Vesalius was already complaining that the traditional method of preparing human skeletons for scientific study was “time consuming, dirty, and difficult,” according to medical historian Anita Guerrini.

Well into the 19th century, Western physicians relied on body-snatching to get skeleton specimens, either paying grave robbers or doing the digging themselves. Countries tried to curb the practice by legalizing the seizure of so-called “unclaimed” corpses, but as the medical profession grew, demand for skeletons outstripped domestic supply. According to journalist Scott Carney, Britain began sourcing its skeletons from colonial India, which would become the world’s primary bone supplier in the 20th century.

“In India members of the Dom caste, who traditionally performed cremations, were pressed into processing bones,” writes Carney in The Red Market, his examination of the illicit body trade. “By the 1850s, Calcutta Medical College was churning out nine hundred skeletons a year. “

More than a hundred years later, Cordell says, he became America’s largest importer of human skeletons by getting them directly from Indian suppliers by mail. After purchasing the Anatomical Chart Company from the widow of medical illustrator Peter Bachin in 1970, the Chicago-area native starting selling bones to doctors and universities that were already buying Bachin’s iconic images.

“We’d open the boxes and [the skeletons] would smell from mothballs because that’s how they kept them fresh,” says Cordell. “I never really knew who I was dealing with.”

It’s likely the origin of these bones was being kept intentionally vague. According to Carney, the Indian public was outraged in the 1980s by reports of criminals robbing graves and funeral pyres”or even committing murder”to get skeletons for the international market.

In 1985, India banned the export of human remains, effectively ending the world’s cheap access to real skeletons of dubious origin. Back in the states, Cordell found himself on a search similar to the one that had turned him to India in the first place.

“I had customers, I had orders, so there was no alternative except to find suppliers of plastic,” says Cordell. This would bring him to Germany, where plastic anatomical skeletons were developed in the grim aftermath of the Nazi era.

“After the second world war, we started to ask in Germany about where the skeletons in universities came from,” says Otto H. Gies, former president of 3B Scientific Group, which created the first plastic skeleton and continues to be a worldwide leader in the anatomical skeleton market. “There were many, many issues about that because nobody wanted a skeleton in his teaching room that came from a concentration camp. And that is why they started to replace those with only plastic skeletons.”

Cordell, who is Jewish, says he was initially intimidated about going into business with Germans, but suppliers like 3B welcomed him and soon he was selling fake skeletons at a scale far beyond that of the real thing.

Skeletons go seasonal

The story of Cordell’s bone business, which, like many anatomical companies at the time, had to reckon with the troubling truth about real human skeletons, might end there if it wasn’t for Cordell’s talent for promotion.

“I had broken [plastic] skeletons, things I couldn’t sell for professional use, so I rented a booth at a Halloween show,” says Cordell. “I put a pile of bones that said “˜two dollars a pound.’ Broken skeletons that were no good were perfect for haunted houses, and the market just took off.”

Timing was everything. In the late “˜80s, people were beginning to decorate their yards for Halloween as they did for Christmas, according to Cordell, and his business became the primary vendor for serious bone fans in need of fake skeletons. Gies says one American company”which sounds a lot like Cordell’s”began having Christmas and Halloween sales promoted with skeletons wearing Walkmans.

“We had to do the glowing-in-the-dark skeleton and all these kind of gimmicks which they could sell for Halloween in America,” says Gies. “At that time for us, that was very exciting and we did that. And then the very conservative professors and teachers here in Germany were upset about us.”

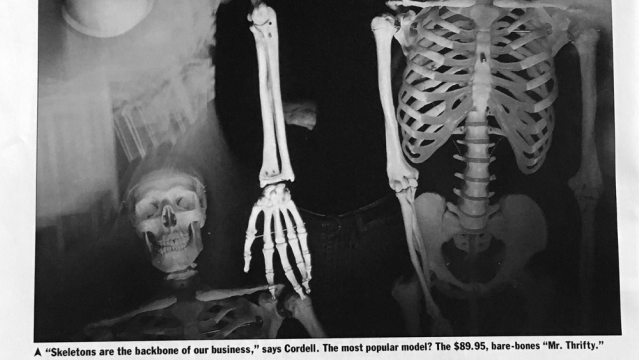

Around the same time, Cordell began selling his own line of bargain-priced artificial skeletons, including the full-sized “Budget Bucky,” a miniature model called “Tiny Tim,” and a three-foot skeleton marketed as “Mr. Thrifty,” which sold for less than $US90 ($127).

“Otto was really jealous when I came up with this three-foot skeleton,” claims Cordell. “That became a huge, huge market. I would bring those in by the container-load.”

“A dream come true”

As Anatomical Chart Company began selling fake skeletons to customers outside the medical field, Cordell himself was entering the public eye. He remembers Good Morning America interviewing him from his “bone room” on Halloween morning and a print story headlined “Someone Has to Do It.”

Soon, the company was branching into the educational toy market with the Brainstorms novelty catalogue and stores like BareBones in the Mall of America, which was run by Cordell’s now-ex-wife Katie Malone. “We had a store in there the day it opened” in 1992, recalls Cordell. “We had skeletons embedded in the exterior of the store.”

A newscast from opening day calls BareBones, which sold a variety of anatomical models and charts, “by far the most unique store you’ll find” in the enormous mall. Among its fans were Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain and Babes in Toyland’s Lori Barbero, who told Gigwise in 2015 that she brought the Seattle band there knowing Cobain “would love it.”

“It’s really great, I bought all these fetuses, anatomy men, and charts and stuff, it’s like a dream come true,” Cobain told Canadian TV station MuchMusic in 1993. “I just went on this rampage of buying all this stuff, and I think I’ve overused it for pictures for the album.”

The “pictures” for that album, In Utero, would end up being a problem. Kmart and Walmart refused to stock the record, which had a photo of flowers and foetus models on the back cover. Eventually, the band released a version of In Utero with the fetuses cropped out, so that “kids who don’t have the opportunity to go to mum-and-pop stores” could buy the record.

According to Cordell, Anatomical Chart Company products were also admired by Hollywood prop masters, who used his wares in movies like Patch Adams, where Robin Williams famously makes a plastic skeleton talk. His artificial skeletons even made into Las Vegas’ Treasure Island Hotel & Casino, where they were given gold chains and tricorn hats in line with the casino’s pirate theme.

“I didn’t have any competition,” says Cordell, “so anyone that was looking for a skeleton, I was the one they went to.”

Legacy of a boneman

As the decade continued, however, these efforts to grow beyond the medical market began cutting into the main business’s bottom line. Skeletons were always just a minor part of the chart company’s sales, and in the second half of the “˜90s, Cordell closed the stores and sold off Brainstorms as the educational toy market wound down. Finally, in 1999, he says, he sold Anatomical Chart Company for $US17 ($24) million

“It was a very, very difficult time,” says Cordell. “It wasn’t fun for me anymore.”

Since then, Cordell has moved into the theatre business, finding success producing shows at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and as “the last investor” in Monty Python’s Spamalot, but his bony legacy lives on. In 2005, his son Adam Cordell entered the fake skeleton business himself as the president of Anatomical Worldwide.

“We still have legacy accounts that buy dozens and dozens of Buckys,” says Liz Huff, director of operations at Anatomical Worldwide. “All the Six Flags parks around the country buy either Bucky or our cheap Chinese one, [Bargain Basement] Barney.”

For anatomical model sellers, however, the Halloween market just isn’t what it once was. These days, according to Huff, even a decorative $US40 ($56) skeleton from Party City or Walmart “looks pretty damn good.”

“Marshall really was a pioneer for increasing not just the use of skeletons in decor, but also the fidelity of the skeletons,” says Huff. “It’s really the hardcore guys that know they need that better detail, that better quality.”

Still, Huff says her company sees “a small uptick” this time of year. So if you find yourself admiring the fine quality or life-like detailing of a fake skeleton this Halloween, you have a Chicago kid who bought a medical chart company strictly as a business he “thought had potential” to thank.

This post was originally published on November 2, 2018.