NASA has worked hard to prevent microbes from hitching rides on our spacecraft and spreading around the solar system, but the agency’s tactics are now woefully out of date. A new report outlines the changes needed to modernise NASA’s planetary protection policies and prevent our germs from contaminating scientifically important targets like Mars.

The new report, released by the Planetary Protection Independent Review Board (PPIRB) late last week, was prompted by recommendations made in 2018 by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which found that NASA’s planetary protection policies were no longer in touch with the modern realities of space exploration. The new report adds some meat to these bones, highlighting the ways in which NASA should upgrade its policies.

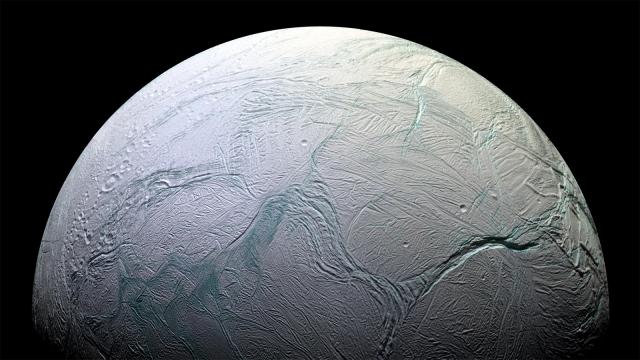

Indeed, given the complexity and scope of future missions, it’s reasonable to ask that NASA reconsider its planetary protection policies, some of which have remained unchanged since they were first implemented in the 1960s and 1970s. This topic is becoming increasingly relevant, given scheduled missions to the Moon (namely NASA’s upcoming Artemis missions in which humans will once again walk on the lunar surface), the pending sample return mission involving the Mars 2020 rover, and an aerial drone to explore Saturn’s moon Titan, not to mention possible missions to explore the subsurface oceans of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Then there are the potential commercial missions in space, such as SpaceX’s farfetched plan to set up bases on Mars.

The inadvertent spread of terrestrial microbes to these places could interfere with our ability to detect native life on these objects, or interfere with unknown alien ecosystems. This prospect is referred to as “forward contamination,” but “backward contamination” — in which alien microbes returned to Earth either deliberately or accidentally — poses risks as well, such as the unleashing of an alien virus on humanity, as outlandish as that might sound.

“Planetary science and planetary protection techniques have both changed rapidly in recent years, and both will likely continue to evolve rapidly,” said Allen Stern, a co-author of the new report and a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, in a NASA press release.

“Planetary protection guidelines and practices need to be updated to reflect our new knowledge and new technologies, and the emergence of new entities planning missions across the solar system. There is global interest in this topic, and we also need to address how new players, for example in the commercial sector, can be integrated into planetary protection.”

The PPIRB report, which included 34 new findings and 43 recommendations, was authored by 12 experts with backgrounds in science, engineering and the space industry. Similar to the National Academies’s findings from 2018, this report found plenty of room for refinements and improvements.

Given that many current policies date back to the 1970s and the Viking expeditions to Mars, the space agency’s planetary protection policies and implementation procedures “should be reassessed,” according to the report, adding that the current guidelines are “anachronistic” and “sometimes unrealistic.”

But while NASA could do more to protect the solar system from contaminants, the authors said it should also worry less about the spread of microbes to places where they couldn’t possibly take root or to locations of little scientific value. As the authors say in the new report, a good portion of NASA’s “scientifically driven planetary exploration missions” involve “scientific cleanliness requirements” that often exceed planetary protection requirements.

The authors advised NASA to explore new technologies to “better categorise exploration targets, create better forward and backward [planetary protection] implementation protocols, and lower [planetary protection] cost and schedule impacts on projects.” It also advises the space agency to conduct planetary protection re-evaluations twice per decade and secure additional funding to make sure its policies are effective.

The PPIRB also said NASA needs to revamp the way it classifies target objects. NASA currently ranks target objects from 1 to 5 in terms of the measures needed to ensure planetary protection. Category 1 objects, for example, require virtually no measures for protection due to “no direct interest for understanding the process of chemical evolution or the origin of life,” according to the report, whereas Category 4 or 5 objects require the strictest levels of protection.

Needless to say, with each increment of category, the protocols get more sophisticated and costly, such as exhaustive sterilisation measures to prevent microbes from hitching a ride on, say, a six-wheeled rover bound for Mars.

As it stands, lunar landers must adhere to Category 2 standards, while Mars landers are designated Category 4. But as the report points out, a one-size-fits-all approach for large objects like the Moon or Mars doesn’t make much sense; instead, scientists should categorise specific geographical areas within these bodies.

On the Moon, for example, areas in which water ice is present, such as at the poles, should be granted Category 2 status, whereas every other lunar surface should be a Category 1. Meanwhile, objects like comets, asteroids, or Kuiper Belt objects should almost automatically be granted Category 1 status. To create these designations, the authors say, scientists should carefully evaluate the surface or subsurface in question, the number of times previous missions have investigated the area, and the chances that an organism could actually survive and potentially reproduce in a particular environment.

On the topic of potentially contaminating Mars, for example, the authors said all previous landed missions “have been treated as though there is a ‘significant’ chance that terrestrial organisms can survive and be transported to areas where life or biosignature detection experiments would be performed,” but new scientific findings “have shown that many areas of the surface are not locations of [planetary protection] concern.”

NASA was also advised to establish “high priority astrobiology zones,” namely regions with high scientific priority for finding either extinct or extant alien life, and “human exploration zones,” that is, regions visited by human explorers. Indeed, human boots on alien grounds will greatly complicate planetary protection — especially a trip to Mars — as crewed landing missions would introduce “orders of magnitude more terrestrial microorganisms” to the surface compared to robotic missions, explained the authors in the report.

Human activity in space also presents a potentially intractable problem as far as the prevention of backward contamination is concerned. NASA currently lists sample return missions as a Category 5, but the PPIRB said this standard of protection won’t be “achievable for human missions returning from Mars,” as the authors write:

Specifically, requirements such as “No uncontained hardware that contacted Mars, directly or indirectly, may be returned to Earth unless sterilised” and “The mission and the spacecraft design shall provide a method to ‘break the chain of contact’ with Mars” appear to drive towards implementation approaches that are difficult, if not impossible, for human missions and their hardware to achieve.

Regarding the return of humans and equipment from Mars, NASA should invest in developing more informed, backward contamination [planetary protection] criteria, considering protection of Earth’s biosphere, the feasibility of mission implementation, and the potential for [on site] hazard characterisation on Mars. Special attention should be paid to assess how astrobiological research can be carried out in the presence of human activities.

That said, the PPIRB said the long journey home to Earth from Mars, which could take over six months, would serve as a reasonable quarantine and evaluation period for the astronauts. Clearly, NASA can’t sterilise astronauts, as per the demands of Category 5 protocols.

The report also made recommendations about future private sector missions to space, whether it’s to establish bases on Mars or dig for valuable minerals on the Moon. NASA is not a regulatory body, but it does play an active role in helping the Federal Aviation Administration to issue launch permits.

Accordingly, NASA could make it very difficult for American space ventures that fail to adhere to planetary protection guidelines. At the same time, NASA should work with the White House, Congress, and the private sector to figure out which government body should manage planetary protection considerations for commercial missions, according to the report.

In terms of next steps, NASA said it’s going to take this new report and use it to start a dialogue with all the relevant parties to “help build a new chapter for conducting planetary missions.”

This discussion is also timely given a recent, controversial paper that claims that many celestial targets — especially Mars — will inevitably be contaminated with terrestrial microorganisms, and as such we shouldn’t waste our time with protection protocols. This remains a minority opinion, but it’s clear that the rationale behind planetary protection needs to be reconsidered and refined.