If you’ve ever been dizzy without a cause — no alcohol in your system, no blunt trauma to the head, no ear infection — you may have experienced benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. It’s a common condition: approximately 10 per cent of people will experience BPPV before they die.

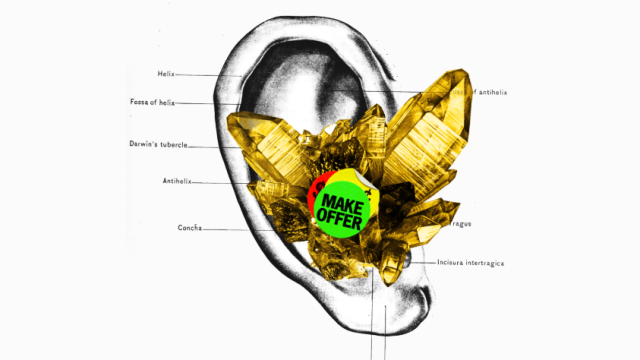

Despite its prevalence, vertigo’s cause borders on the mystic. Deep inside the ear, thousands of tiny crystals help you keep your balance. But if something knocks the crystals out of place, they’ll set you spinning.

But the more I read about ear crystals, the less I felt I understood. What is a crystal? Why, exactly, are we so dependent on microscopic pieces of calcium carbonate in our ears? And can I sell mine on the booming healing crystal market?

My first point of contact was Timothy Hain, professor emeritus at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the principal physician at the Chicago Dizziness and Hearing clinic.

He told me that every organism needs to know which way is up and which way is down, but there’s no single solution to this problem. Plants, for example, have little starch-filled organelles in their roots, which may help them push deeper into the soil.

Some aquatic invertebrates like lobsters have a tiny pouch in their heads that capture and hold grains of sand. Fish have a few large crystals, each called an otolith. And mammals have tons of tiny crystals called otoconia.

In human ears, the gravity sensors are structured a bit like a toothbrush covered in extra-crunchy paste: There’s a bed of motion-sensing hairs (the bristles), topped with a dollop of goop (the toothpaste), upon which the crystals rest.

When the otoconia slide, they tug the hair cells as they go. The cells transmit that information through a cranial nerve to the brainstem, letting you know where your head is in space. While these ear crystals are sticky, they aren’t actually embedded in anything. That’s good, because it means they can constantly shift alongside our centre of gravity. But it’s also bad, because they can escape. And they do.

Otoconia live in two little cavities called the utricle and saccule. In a design flaw that should have Creationists shaking, the utricle actually has a tiny opening at the top. When you’re really unlucky, a crystal or two will pop out of this skylight and into one of the ear’s three semicircular canals, which take up residence nearby. That’s when things get topsy-turvy.

Otoconia in the utricle detect head tilts and linear acceleration, or how fast the body moves forward. But the semicircular canals activate in response to angular acceleration, which is the change in an object’s rotation.

When you feel dizzy in the middle of a pirouette or, more likely, your third ride on the Gravitron at the county fair, it’s because the liquid in the canals is sloshing around. But if rogue otoconia have jammed up the system, you can feel that same spinning sensation standing up, laying down, or bending over.

For most of human history, the cause of vertigo was unknown, said Carol Foster, an otolaryngologist at the University of Colorado, Denver School of Medicine and author of Overcoming Positional Vertigo.

It was only in the mid-1800s that scientists began to understand what the inner ear even did. Their methods were not PETA-approved—they drilled into the heads of live pigeons and damaged or removed parts of their labyrinth.

When they noticed the pigeon’s eyes spun around in their sockets in response to this assault, and the birds struggled to stand up or walk around, the scientists realised they were tinkering with the seat of balance.

It took another century for doctors to actually develop a solution for vertigo. In 1980, John Epley first described his eponymous manoeuvre, now the standard course of treatment for BPPV. It’s a physically involved, multi-part process. Doctors first spin the patient’s head in a way that triggers their vertigo. The goal is to see which way their eyeballs roll.

If the eyes jump up, that indicates the crystals are lodged in the posterior canal; if they move sideways, they’re stuck in the lateral canal; and if they spin downward, they’re blocking the anterior canal. Having identified the problem area, doctors swiftly turn the patient’s head in the appropriate direction with karate-like precision in order to spin the crystal out of the canal.

“It’s like the Cracker Jack game with the marble,” Foster told me. Done successfully, it alleviates dizziness in more than 90 per cent of BPPV patients.

Of course, not everyone with a loose crystal develops vertigo. Otoconia can dissolve, or vestibular dark cells, which exist only in the inner ear and help to regulate homeostasis, can absorb them. And not all crystals are equally troublesome.

When we’re born, we have thousands more otoconia than we need, but over time their numbers dwindle, and those that are left show signs of age. “In young people, the crystals are pretty, they have this hexagonal symmetry — they look like a piece of quartz,” Hain said.

“In old people, they look moth-eaten — they’re raggedy.” That might be why older people are more likely to experience BPPV: their crystals are more likely to break apart and drift away.

Listening to Hain describe this inevitable decay, I realised just how short life really is. And I can’t help but wonder, could those of us whose crystals are still young and beautiful make a quick buck?

On a sun-beaten afternoon in August, I took the train to Maha Rose, a holistic healing centre in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. At the end of a meandering walk past apothecaries, beer gardens, and the apartment building where Lena Dunham’s character lived in Girls, I found a bright red door and a shingle advertising acupuncture, crystals, and reiki.

I was there to meet Sadie Kadlec, a crystal healer. Many cultures have used earth elements in magic or medicine. But when it comes to hawking rocks, ancient Egyptian pharaohs have nothing on contemporary wellness culture, which has pulled the formerly fringey New Age practice into the mainstream.

Practitioners use different coloured stones, which they claim can align and enhance the body’s energy centres, or chakras. (As you may already know from Instagram, rose quartz, being pink, supposedly works the heart chakra.)

The fact that there is no evidence crystals have any special powers hasn’t stopped them from becoming a billion-dollar industry.

Over coffee at a nearby cafe, I told Kadlec what I’d discovered: Many animals have calcium carbonate crystals in their ears. But just as diamonds and graphite are both pure carbon, calcium carbonate can come in different forms. Fish otoliths, for example, are typically aragonite, while human otoconia are calcite.

“It doesn’t surprise me it’s part of our makeup,” Kadlec said of calcite. The crystal can come in many colours and, she claimed, serve many different energetic purposes, which may be why online retailer Energy Muse calls it “the multi-vitamin of the soul.” The calcite in our ears is white, the colour of the crown chakra, where Kadlec said it helps to restore balance of the metaphysical kind.

Kadlec mentioned a transparent form of the stone, called optical calcite, or Iceland spar. Historians think it’s the “sunstone” mentioned in medieval Norse texts — a polarising crystal that helped Viking navigators find the Sun on a cloudy day. In healing circles, Kadlec told me, it works much the same way, by “helping you see where your horizon is, and where to go next.”

Aragonite also comes in several shades. In fish heads, it’s usually white, but in the world of healing crystals, it’s often a ruddy hue. That makes it a crystal for the root chakra, Kadlec told me, so, she claimed, it helps people stay grounded.

Maha Rose’s crystal shop sells both of these calcium carbonate crystals. On Etsy, you can find otolith jewellery — typically a combination of fish ear stones and another healing mineral, like snapper earrings suspended from pebbles of rose quartz or bracelets with boho and sea glass. But there are a few major obstacles to monetising the potential healing power inside my ears.

The first is that I would suffer severely without my ear crystals. Many people live with inner ear damage, which can be triggered by untreated or severe infections, like vestibular neuritis, or certain types of ototoxic antibiotics, like gentamicin.

These patients “are pretty unhappy for quite a long time,” Hain told me. They struggle to coordinate their movement. “It’s like their eyes are painted on their head,” he said. And that increases their risk of falls. When they do drop, some don’t go down so much as sideways, the result of their impaired sense of gravity.

Most people find a new equilibrium after a year or two, Hain said, but they probably don’t play sports or drive after dark, and they rely on their remaining senses to compensate for what they’ve lost.

Even people with healthy ears experience a dwindling crystal supply. Some scientists think otoconia simply cannot replenish themselves, while others speculate they grow back more slowly than they degrade.

Those who think otoconia are finite may find support in an old NASA experiment, Hain told me. In the 1960s, scientists put 12 guinea pigs in a centrifuge, and spun the machine at 400 Gs. (For reference, that’s 44 times the force of acceleration experienced by fighter pilots.)

They dissected six of the rodents immediately, and found that almost all of the otoconia had left the saccule and utricle. Six months later, they dissected the other guinea pigs and discovered the lost otoconia did not return, and new otoconia failed to grow. Humans and guinea pigs are wildly different animals, but if I sold the crystals in my ears today, it’s safe to assume I’d never get them back in full.

That makes harvesting my otoconia ethically fraught. Right now, the vast majority of healing crystals come from mines (a smaller percentage is synthesized in laboratories). People pull honey-coloured tiger’s eye and milky-green jade out of the earth — often to the detriment of their health and that of the surrounding environment.

For many healers like Kadlec, ethically sourcing crystals is one of the most difficult parts of the job. There’s little transparency, and the odds of acquiring crystals linked to conflict is high. I might be able to freely consent to otoconia extraction, but few would want to buy calcium carbonate with such a troubling origin story.

The other, more commercial issue is that ear crystals are impossibly small—roughly one-fifth the width of a human hair. Almost everything we know about them comes from electron microscopes, which magnify objects up to a million times their real size.

The resulting images show the pointy crystals that live inside us like miniature Washington Monuments. But to the rare doctor who’s seen otoconia with their own two eyes, they’re individually indistinguishable, and collectively no more than a speck of white paste.

In the world of healing crystals, Kadlec says many people mistakenly think that “bigger is better.” Surely, the thinking goes, an 5kg quartz “tower” should outperform a pebble. But Kadlec believes a crystal’s size is irrelevant.

At a certain point, she claims, students in her advanced class can learn to adjust vibrational energy with only their mind and body, no stones involved. But for people who are still using crystals to alter their chakras, Kadlec claims you need to see and feel the energy from the object—an impossibility with my puny otoconia.

Talking to Hain and Foster, two seasoned veterans of the vestibular system, I was struck by how much mystery they still see in the inner ear. They can explain how and why it works and even cure patients of vertigo. But there’s something about the labyrinth, and our complete dependence on its continued function, that defies total comprehension.

So though I’m ultimately unable to sell my ear crystals, I appreciate them more than ever.