New York’s new KGB Museum is, suffice it to say, a very strange place. The cinderblock-walled space occupies the ground floor of a pricey condo complex, and it recently underwent its “ribbon-cutting” ceremony, with a metallic rope serving as ribbon, which was cut through with a power saw.

Inside the museum sit dozens of glass cases featuring a massive (and occasionally baffling) panoply of Soviet and Russian spy gear, flanked by propaganda posters and uniformed mannequins.

The overall theme sits in an awkward position between its Spy v. Spy-style camp and brief reflections on the actual horrors inflicted by the Soviet bloc’s secret police and formal intelligence services.

With Russian intelligence agencies and the possibility of a new Cold War at the forefront of some American minds, it’s hardly a surprise that someone would choose to open a museum dedicated to the Eastern Bloc’s legacy of spycraft. The collection spans from the pre-World War II period to the end of the Cold War and beyond.

The KGB Museum, a project of Lithuanian father-daughter collector team Julius Urbaitis and Agne Urbaityte, sits at the junction of the US public’s Russia-related anxieties in 2019.

Per The Wall Street Journal, Urbaitis, a 55-year-old marketing executive, said the collection has been underway for 30 years. His personal stack of artefacts started in Urbaityte’s dance studio, which was based out of a former nuclear bunker in Lithuania. The 3500-strong display is both assembled from their collection, as well as items on loan from other collectors.

“I have a collector’s spirit,” Urbaitis told the Journal. “Every artefact is like an achievement when you find it, like a hunter who kills a wolf. Especially the ones that are one of a kind in the world.”

And the KGB Museum does have a specialised collection, with artefacts dating back all the way to the KGB’s pre-1954 predecessors, the Cheka, NKGB, NKVD and MGB.

It includes a lamp that allegedly belonged to none other than infamous Soviet strongman Josef Stalin, which is staged in a mock interrogation room and angled to glare directly in passing visitors’ faces. Also, his gramophone is on display.

You can peer through a prison-style door’s observation slit to watch footage of what life was like for Soviet prisoners of conscience. The audio from these prisoner films can be heard at a low level throughout the museum, giving the space an eerie ambience.

And after viewing a mockup of a sophisticated surveillance device disguised within a tree branch, your tour guide encourages you to don a modern reproduction of a KGB officer’s leather trench coat and pose for a photo.

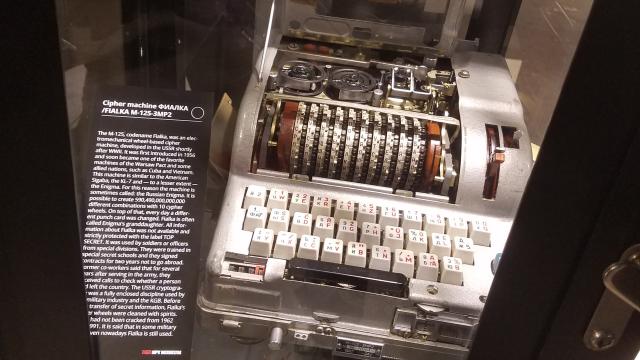

There’s much for military and intelligence buffs to see here, while the bulk of the show is composed of innumerable examples of covert communications gear — mostly radios, including sets hidden in luggage.

There are KVADRAT ultraviolet lighting devices, which were used to detect fake documents, reveal hidden cryptographic symbols and check covertly marked money used for bribery.

Elsewhere visitors will find a KGB-modified Imbir movie camera, also used by the German Stasi and agents in Czechoslovakia, with internal parts modified to save space for up to 61m of special thin film and covered in a soundproof case for concealment.

There are cameras hidden in packs of cigarettes, which snapped a photo when a “cigarette” was moved up.

Perhaps the most inconspicuous photo-taking device is a gold-plated KGB ring from 1970-1980 that contains film wrapped around the finger, as well as a hinge that contains a fixed-focused, high-definition, single-shot camera.

One exhibit showcases special phones used by KGB officers, including one with integrated memory that could be used to detect a call’s origin. Others show off Panasonic phones with built-in bugs, circuitboards revealed to show where the modified hardware was attached.

There’s even a letter remover, a simple tool designed to allow state agents to open and re-seal mail with no indication it was ever accessed by anyone but the recipient.

Other equipment on display had a more lethal purpose. There’s a tube of lipstick that can fire a bullet, a pen that does the same, and a replica of the infamous, ricin-pellet-tipped umbrella of the type allegedly used in the 1978 assassination of Bulgarian dissident-in-exile Georgi Markov.

The only other replica in the collection, Urbaityte told Gizmodo, is that of a Soviet bug hidden in a Great Seal gifted to US ambassador Averell Harriman in 1945 (sometimes known as The Thing).

While the curators were Urbaitis and Urbaityte, the actual financial backing of the museum remains elusive.

Urbaityte told Gizmodo that the museum was owned by Nothing Secret Group, Inc., a company in Urbaitis’s name, according to the tax office that prepared the documentation. However, she characterised the company in a separate email to another GMG reporter as “established by [an] American citizen who does not want to be publicized”.

As Smithsonian Magazine noted, this is a uniquely capitalist look at Russian spycraft — James Bond with a dash of The Death of Stalin.

For the privilege of viewing this extensive array of admittedly ingenious tools of espionage and oppression, visitors should be prepared to fork over $US25 ($36) for an adult admission, or $US43.99 ($63) for a guided tour.