Traces of a rare and expensive blue pigment, called ultramarine, have been detected in the teeth of a woman who died in Germany nearly 1,000 years ago. The discovery suggests women played a more prominent role in the production of manuscripts during the medieval period, and that ultramarine was more available in Europe than previously assumed.

Blue pigments are quite rare in nature. During the medieval period, only a few sources of blue pigment were known, including ultramarine, which is made by grinding and purifying lazurite crystals from lapis lazuli, an ornamental stone sourced from east Persia, now Afghanistan.

During the European medieval period, between the 5th to 15th century AD, ultramarine was used by scribes and painters to adorn their manuscripts with the vivid blue colour, which has been referred to as the most perfect colour.

New research published today in Science Advances uncovers evidence of ultramarine in the dental plaque of a woman found buried next to a medieval monastery in Germany. The presence of blue pigment in her teeth suggests she, and possibly her female peers, contributed to the preparation and/or production of coloured medieval manuscripts, also known as illuminated texts.

It’s an important discovery because women were previously thought to have minimal involvement in this industry.

Among the sources of blue pigment during medieval times, ultramarine was easily the most expensive, “reserved along with gold and silver for the most luxurious manuscripts,” according to the authors of the new study. Consequently, the use of ultramarine in illuminated works was limited to “luxury books of high value and importance,” and only scribes of “exceptional skill would have been entrusted with its use.” But historians have found it difficult to identify the contributions of women.

“First, women tended not to sign the books they made, and many of such anonymous books have been falsely assumed to have been written by men,” Christina Warinner, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the lead author of the new study, told Gizmodo. “Additionally, records from women’s monasteries were less frequently kept and preserved, and so we know less about their activities.”

The unexpected discovery of ultramarine in the dental tartar, or dental calculus, of an 11th century woman in rural Germany is shedding new light on this poorly understood time and the roles played by women during the production of illuminated texts. What’s more, the study is providing a new method in which the remains of scribes and artists can be used to infer the roles played by both women and men during the medieval period, including the production of expensive sacred books.

Back in 2014 during an earlier investigation, Warriner discovered the microscopic remnants of plants in the woman’s dental calculus, but she also found numerous particles with a distinctly blue colour. This discovery prompted a second look, so Warriner launched a new analysis, assembling a team of specialists, including historians and physicists, to take a closer look.

The woman’s teeth were radiocarbon dated to between 997 and 1162 AD. Her skeleton was normal, exhibiting no obvious signs of illness or trauma. The woman, who died between the age of 45 and 60, was buried next to a medieval church-monastery complex in Dalheim, Germany, of which little is known.

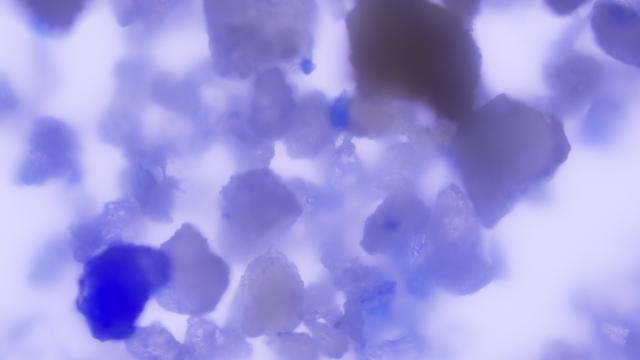

Using a technique known as sonication, the researchers released over 100 calculus fragments and mineral particles into ultrapure water for analysis.

“We first discovered the blue particles using microscopy,” said Warriner. “To identify their elemental composition, we used scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy. Then to confirm their mineral structure, we used Raman spectroscopy. The last technique was particularly important because it allowed us to identify both lazurite and phlogopite, two different minerals found in lapis lazuli.”

The particles entered into the woman’s teeth not at once, but over a protracted period of time. A likely explanation is that she was a scribe or a book painter who either created the illuminated texts, or was employed to prepare the materials. As to how the pigment got into her mouth, the researchers speculate that she licked the end of the brush while painting.

“We think she was likely using her lips to shape the brush to a fine point,” explained Warriner. “This a common technique used by painters and was even described in medieval artist manuals.”

Other hypotheses were considered in the paper, including the medicinal use of lapis lazuli and “emotive devotional osculation”—a fancy way of saying she may have read the books with religious intensity, kissing and even licking the painted images as a sign of devotion. These alternative scenarios, however, were deemed less likely.

Warriner said the new finding offers three main take-away messages.

First, the discovery demonstrates that lapis lazuli was traded further and to more remote areas during this period than previously thought. The pigment found in the teeth of this specimen would have travelled more than 3,700 miles (6,000 km) to reach Dalheim, showing that the substance wasn’t exclusive to major cities and artistic centres.

Second, the discovery shows that women had access to this rare and valuable pigment.

“We knew some women were involved in painting, but few records have been kept about the materials they used, and certainly finding lapis lazuli was a surprise,” said Warriner. “This makes us rethink the role and status of women in book production.”

Lastly, the study is presents a new way to identify artists in the archaeological record—one that’s not dependent on the survival of books, many of which have been destroyed over the past thousand years. Warriner said this could potentially give us “a different and less biased view of craft production and gender roles during the Middle Ages.”

Nicholas A. Herman, curator of manuscripts at the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, thought the new study was “fascinating.” The use of bio-archaeology to study medieval art is still in its infancy, he said, but if the main theory presented in the new paper is correct, “it will corroborate some of what we know from the literary record, and since evidence from this period is so slim, any additional detail is helpful.” Herman said he’ll be interested to see what art historians who specialize in this period and the creation of illuminated manuscripts will make of it.

Christopher Duffin from the Department of Paleontology at the Natural History Museum in London said the identification of lapis lazuli flakes in the dental coatings is “clearly correct” and an “excellent example of relatively new analytical techniques being applied to formerly obscure problems to yield fascinating new data and the opening up of new fields of enquiry.” That said, he believed more work should have been done to either prove or discount the suggestion that the lapis lazuli served medical purposes. He even offered some advice on how the researchers could do so.

“The authors state that the blue flecks were originally found in samples prepared for the identification of plant micro-remains in a 2014 study,” Duffin told Gizmodo. “If they were successful in isolating identifiable plant remains, it might be instructive to compare the flora identified with medicinal plants commonly combined with lazurite in medicines from medieval and early modern recipes.”

Herman said the role of women in medieval artistic culture was largely ignored by previous generations of scholars, but the past few decades have seen huge advances in our knowledge and understanding of the role of women in art production.

“So often, women were written out of the historical record because it was predominantly men who signed legal contracts and engaged in writing about art,” Herman told Gizmodo. “Only by looking very closely at new kinds of evidence can we begin to discover the true importance of female artisans.”