As the last Ice Age was coming to an end, and as the first settlers arrived in North America, two distinct populations emerged. One of these groups would eventually go on to settle South America, but as new genetic evidence shows, these two ancestral groups – after being separated for thousands of years – had an unexpected reunion. The finding is changing our conceptions of how the southern continent was colonised and by whom.

Illustration: DEA Picture Library/De Agostini/Getty Images

Scientists who study the settling of North and South America are rarely in agreement, and there are competing theories about who the first migrants were, how they arrived, and when.

Research from 2015 suggests a single wave of settlers arrived to North America from Eurasia, after which time they diverged into two ancestral branches, a northern branch and a southern branch. It isn’t entirely clear where or exactly when this happened, but genetic evidence suggests the divorce occurred between 18,000 to 15,000 years ago.

That’s a few thousand years before an ice-free interior corridor appeared between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets, making North America accessible to settlers. So this ancestral split happened either in Beringia or among a group of settlers who made their way into North America after having travelled along a coastal route – an altogether distinct possibility, given new evidence published earlier this week.

[referenced url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2018/05/new-evidence-reveals-a-17000-year-old-coastal-route-into-north-america/” thumb=”https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/t_ku-large/efh2wx98uzzirmpadzb2.jpg” title=”New Evidence Reveals A 17,000-Year-Old Coastal Route Into North America” excerpt=”The first people to cross into North America from Eurasia did so by travelling through the Bering Strait, or so the theory goes. A new theory has emerged proposing a coastal route into the continent, but evidence has been lacking. A recent analysis of boulders, bedrock and fossils in Alaska is now providing a clearer picture, pointing to the emergence of a coastal route some 17,000 years ago.”]

A research paper published today in Science suggests the latter scenario is the correct interpretation, and that the northern and southern ancestral groups reconverged and interbred thousands of years after splitting apart – an event the authors say could have only happened in North America, south of the receding ice sheets.

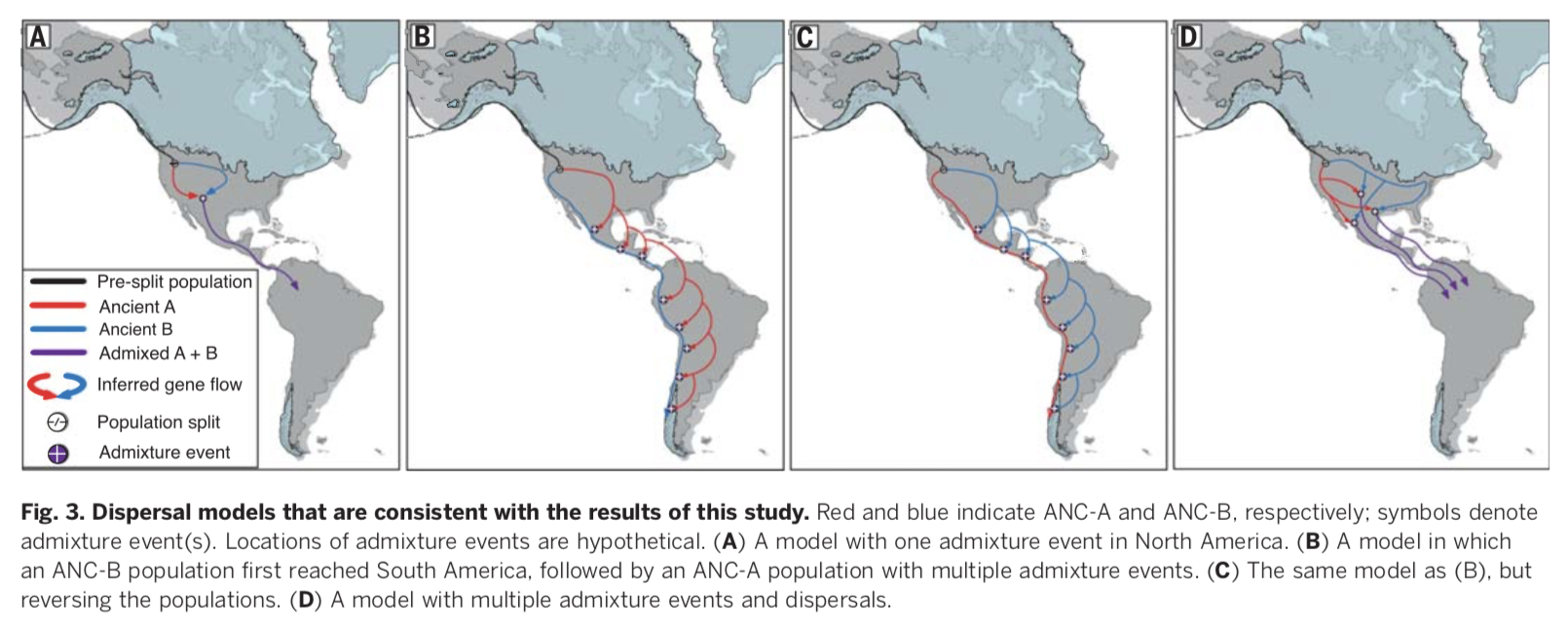

What’s more, the authors of the new study say this intermingling of ancestral populations happened before humans ventured into South America, or as the southern continent was receiving its first human visitors. In total, the researchers presented four different possibilities, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Image: C. L. Scheib et al., 2018/Science

As noted, an ancestral split occurred among North America’s first migrants, and they remained separated from each other long enough for two distinct genetic lineages to emerge. A popular interpretation is that the northern branch spread eastward towards the Great Lakes region, possibly following the retreating glacial edges, and eventually giving rise to many Native communities living today in the the East.

Meanwhile, the southern branch travelled southward along the Pacific coast, inhabiting islands along the way, and finally arriving in the southern continent where they gave rise to all Central and South American indigenous populations.

The new research, led by Christiana Scheib from the University of Cambridge, suggests it wasn’t as clear cut as this. These two populations, the study shows, came together prior to, or during, the peopling of Central and South America. As a result, the majority – if not all – of South America’s indigenous populations still contain traces of northern branch DNA.

This conclusion was reached after analysing 91 ancient genomes of indigenous people who lived in California and Southwestern Ontario. The DNA analysis also shows that the Clovis people, named after their distinctive stone tools, were closely related to the southern branch.

The intermingling, or admixture, of northern and southern branch DNA happened either in North America before the southern branch made it to South America, or it happened along the migration route into South America, at least a few thousand years after the initial ancestral split.

Genetic evidence in the new study shows that present-day indigenous populations living in both Central and South America have retained between 42 to 71 per cent of the northern branch genome, which is significant.

Quite unexpectedly, the researchers found the highest proportion of northern branch DNA among indigenous populations living in southern Chile. This area is home to the Monte Verde archaeological site, which at 14,500 years old is one of the oldest known settlements in the Americas.

“It could be evidence for a vanguard population from the northern branch deep in the southern continent that became isolated for a long time – preserving a genetic continuity,” said Scheib in a statement.

“Prior to 13,000 years ago, expansion into the tip of South America would have been difficult due to massive ice sheets blocking the way. However, the area in Chile where the Monte Verde site is located was not covered in ice at this time.”

Scheib and her colleagues say this new evidence is a heavy blow to the theory that the two ancestral branches split while they were still in Beringia, and that multiple waves of genetically distinct populations ventured into North America during this initial migration period.

Instead, the researchers say a single wave of Ice Age humans migrated to the southern boundary of the Laurentide ice plate, and the genetic split happened afterwards, likely in the northwest corner of North America.

“Very interesting and exciting research findings,” Ben Potter, a professor of anthropology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who is not affiliated with the new study, told Gizmodo.

“Overall, this is a welcome study of North American Native populations, who have been underrepresented in many previous studies. The conclusions about splits and admixture appear warranted from the data – however, the geographic locations of these splits and colonisation processes will require archaeological data and models.”

Potter’s primary concern about the new paper is the assumption that the ancestral split occurred in North America south of the glacial ice and from a population that made its way into the continent along the coast – a claim he says is “entirely unwarranted”.

He says the four speculative models presented by the researchers is missing “one obvious alternative”, namely a split of the ancestral populations in Beringia, with one group moving along the coast and one group moving along the interior route, and eventually reconverging in North America, as per the new genetic data.

Potter also takes exception to the claim made by the authors that “ongoing gene flow” among eastern Siberian and Beringian populations would have precluded the emergence of genetically distinctive populations. Indeed, the idea that Beringia was a “land bridge” is a bit of a misnomer; it was a massive landmass unto itself, and no human at the time would have considered it a mere passageway.

“Beringia represents a vast area with many ecologically distinct areas,” said Potter.

“There is also clear evidence for occupation hiatuses in various parts of Northeast Asia and reoccupation events. The assumption that Siberian ancestors were anywhere near Beringia is unsupported by evidence. Given our very limited understanding of these very early populations, we should be cautious in allowing for multiple models.”

In a press release, the authors of the new study suggest the reconvergence happened about 13,000 years ago, but Potter doesn’t buy it, saying the timing is “effectively unknown” and that many different scenarios are possible with genetic data.

“I look forward to continued collaboration between geneticists and archaeologists to fully form colonisation models that benefit from both rich datasets,” he said.

Remember what I said earlier about scientists in this field rarely coming to agreement? Given the complexity of American colonisation, and the frustrating lack of both archaeological and genetic evidence, it’s hard to blame them. But as time passes, and as more data accumulates, hopefully a consensus will start to emerge.

[Science]