Acclaimed epic fantasy author Brandon Sanderson is known for the Mistborn series as well as The Stormlight Archive – including last spring’s hugely popular third book in that series, Oathbringer. But the prolific writer has a new YA book on the horizon, called Skyward, and we are happy to exclusively share a special excerpt.

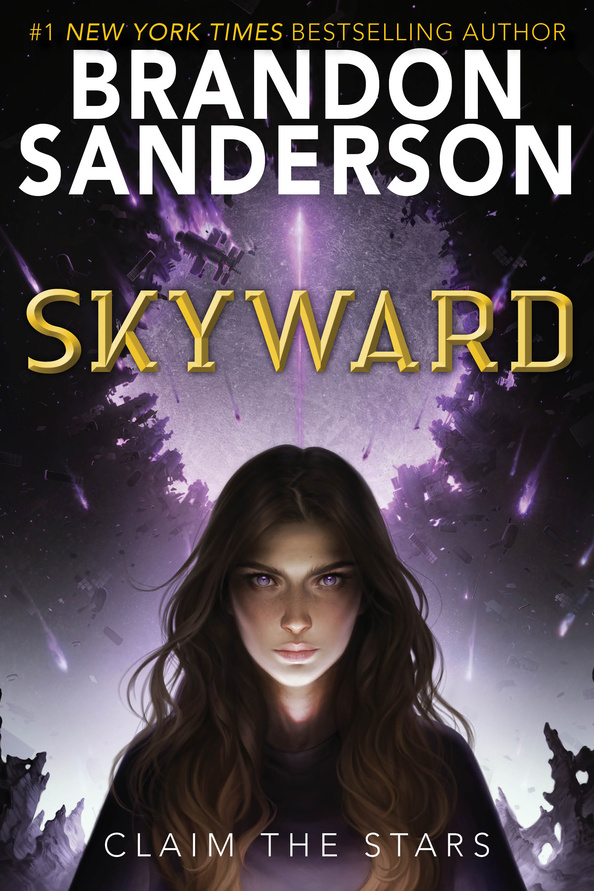

A preview of the cover for Brandon Sanderson’s Skyward.Image: Charlie Bowater/Regina Flath (Delacorte Press)

Here’s a summary of Skyward, which Sanderson calls “a book I’ve been wanting to write for a very long time“.

Spensa’s world has been under attack for hundreds of years. An alien race called the Krell leads onslaught after onslaught from the sky in a never-ending campaign to destroy humankind. Humanity’s only defence is to take to their ships and combat the Krell. Pilots are the heroes of what’s left of the human race.

Becoming a pilot has always been Spensa’s dream. Since she was a little girl, she has imagined soaring above the earth and proving her bravery. But her fate is intertwined with that of her father – a pilot himself who was killed years ago when he abruptly deserted his team, leaving Spensa’s chances of attending Flight School at slim to none.

No one will let Spensa forget what her father did, but she is determined to fly. And the Krell just made that a possibility. They have doubled their fleet, which will make Spensa’s world twice as deadly… but just might take her skyward.

“Skyward was born, much like Mistborn, with me taking two ideas and mashing them together to see where they went … and they went someplace incredible,” says Sanderson in a press release. “I saw in this project a chance to both play in a space I loved and do some very interesting things with story and theme. It wasn’t until this year that I got the personalities of the characters right, but I really got excited when I found a place for this in the lore of stories I’d been creating.”

And here’s the full cover:

The full cover of Sanderson’s new book. Jacket art by Charlie Bowater, design by Regina Flath. Image: Charlie Bowater/Regina Flath (Delacorte Press)

Skyward is set to be released 6 November 2018, and you can pre-order it here. Publisher Random House will be posting content regularly in the weeks leading up to the release on BrandonSanderson.com and the Underlined online teen community. Each week the author will also participate in an online book club Q&A on Underlined. Enjoy the excerpt below!

Excerpt copyright © 2018 by Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC. Published by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

PROLOGUE

Only fools climb to the surface. It’s stupid to put yourself in danger like that, my mother always says. Not only are there near-constant debris showers from the rubble belt, but you never know when the Krell will attack.

Of course, my father travelled to the surface basically every day – he had to, as a pilot. I suppose by my mother’s definition, that made him extra foolish, but I always considered him extra brave.

I was still surprised when, one day after years of listening to me beg, he finally agreed to take me up with him.

I was only seven years old, though in my mind, I was completely grown up and utterly capable. I hurried after my father, carrying a lantern to light the rubble-strewn cavern. A lot of the rocks in the tunnel were broken and cracked, most likely from Krell bombings – things I’d often experienced down below as a rattling of dishware or trembling of light fixtures.

I imagined those broken rocks as the broken bodies of my enemies, their bones shattered, their trembling arms reaching upward in a useless gesture of total and complete defeat.

I was a very odd little girl.

I caught up to my father, and he looked back, then smiled. He had the best smile, so confident, like he never worried about what people said about him. Never worried that he was weird or didn’t fit in.

Of course, why should he have worried? Everyone liked him. Even people who hated things like ice cream and playing swords – even whiny little Rodge McCaffrey – liked my father.

My father took me by the arm and pointed upward. “Next part is a little tricky, Spensa. Let me lift you.”

“I can do it,” I said, and shook off his hand. I was grown up. I’d packed my own backpack and I’d left Bloodletter, my stuffed bear, at home. Stuffed bears were for babies, even if you’d fashioned your own mock power armour for yours out of string and broken ceramics.

Granted, I had put my toy starfighter in my backpack. I wasn’t crazy. What if we ended up getting caught in a Krell attack and they bombed our retreat, so we had to live out the rest of our lives as wasteland survivors, devoid of society or civilisation?

A girl needs her toy starfighter with her, just in case.

I handed my backpack to my father and looked up at the crack in the stones. There was… something about that hole up there. An unnatural light seeped through it, something wholly unlike the soft glow of our lanterns.

The surface… the sky! I grinned and started climbing up a steep slope that was part rubble, part rock formation. My hands slipped and I scraped myself on a sharp edge, but I didn’t cry. The daughters of starfighters did not cry.

The crack in the cavern roof looked a hundred feet away to my eyes. I hated being so small. Any day now, I was going to grow tall, like my father. Then, for once, I wouldn’t be the smallest kid around. I’d be tall, and I’d laugh at them from up so high, they’d be forced to admit how great I was.

I growled softly as I reached the top of a rock. The next handhold was just out of reach. I eyed it. Then I jumped, determined. Like a good Defiant girl, I had the heart of a stardragon.

But I also had the body of a seven-year-old. So I missed by a good two feet.

A strong hand seized me before I could fall too far. My father chuckled, holding me by the back of my jumpsuit, which I’d painted with markers to look like his flight suit. He pulled me onto the rock beside him, then reached out with his free hand and activated his light-line.

The device looked like a metal bracelet, but once he engaged it by tapping his thumb and little finger together, the band glowed with a bright molten light. He touched a stone above, and when he drew his hand back, it left a thick line of light, like a glowing rope, fixed to the rock. He wrapped the other end around me so it fit snug under my arms, then detached it from his bracelet. The glow there faded, but the luminescent rope remained in place, attaching me to the rocks.

I’d always thought light-lines should burn to the touch, but it was just warm. Like a hug.

“OK, Spensa,” he said. “Try it again.”

“I don’t need this,” I said, plucking at the safety rope. “Humour a frightened father.”

“Frightened? You aren’t frightened of anything. You fight the Krell.”

He laughed. “I’d rather face a hundred Krell ships than your mother on the day I bring you home with a broken arm, little one.”

“I’m not little. And if I break my arm, you can leave me here until I heal. I’ll fight the beasts of the caverns and become feral and wear their skins and – ”

“Climb,” he said, still grinning. “You can fight the beasts of the caverns another time, though I think the only ones you’d find have long tails and buckteeth.”

I had to admit, the light-line was helpful: I could pull against it to brace myself. We reached the crack, and my father pushed me up first. I grabbed the lip and scrambled out of the caverns, reaching the surface for the first time in my life.

It was so open.

I gaped, standing there, looking up at… at nothing. Just… just… upness. No ceiling. No walls. I’d imagined the surface as a really, really big cavern. But it was so much more, and so much less, all at once.

Wow.

My father heaved himself up after me and dusted the dirt from his flight suit. I glanced at him, then back up at the sky. I grinned widely.

“Not frightened?” he asked. I glared at him.

“Sorry,” he said with a chuckle. “Wrong word. It’s just that a lot of people find the sky intimidating, Spensa.”

“It’s beautiful,” I whispered, staring up at that vast nothingness, air that extended up into an infinite grayness, fading to black. It was darker than I’d imagined, but enormous blocks of light shone here and there far above, providing light to the surface. There was nothing between us and them. “There’s so much of it. But it’s also empty.”

He knelt beside me. That darkness above, the shifting mass of black shapes that included some blocks of light, must be the rubble belt. Our planet, Detritus, was protected and hidden by a huge veil of broken refuse that was way up high, even outside the air, in space.

It was left over from some great space battle from a long time ago. And there were tons of layers of it, the junk all rotating, churning, colliding. I saw lights shining down from some chunks, so some things up there still worked, providing illumination to a surface where nobody lived.

“The Krell live up there?” I asked. “Beyond the debris field?”

“We assume so,” Father said. “Nobody knows for certain. So much was destroyed during the wars before we fled to this planet.”

“How… how do they find us?” I asked. “There’s so much space up here.” The world seemed a much larger place than I’d imagined in the caverns below.

“They can sense when people gather together, somehow,” Father said. “Any time the population of a cavern gets too big, the Krell attack and bomb it. They have devices that can collapse caverns even far beneath the surface.”

The only way we survived was by splitting into small clans and constantly staying on the move. Never stopping in the same cavern for too long.

Except for the starfighters, who were gathering and building a base. Fighting back.

“Where’s Alta Base?” I asked. “You said we’d come up near it. Is that it?” I pointed toward some suspicious rocks. “It’s right there, isn’t it? I want to go see the starfighters.”

My father leaned down and turned me about ninety degrees, then pointed. “There.”

“Where?” I searched the surface, which was basically all just blue-grey dust and rocks, with craters from fallen debris from the rubble belt. “I can’t see it.”

“That’s the point, Spensa. We have to remain hidden.” “But you fight, don’t you? Won’t they eventually learn

where the fighters are coming from? Why don’t you move the base?”

“We have to keep it here, above Igneous. That’s the big cavern I showed you last week.”

“The one with all the machines?”

He nodded. “Inside Igneous, we found manufactories; that’s what let us build starships to fight back. We have to live nearby to protect the machinery, but we fly missions anywhere the Krell come down, anywhere they decide to bomb.”

“You protect other clans?” I asked, frowning. I didn’t know a lot about this – everyone tried to keep it secret from me and ignored my questions, even though I was basically grown up.

He turned my head toward him and raised his finger. “To me, there is only one clan that matters: Humankind. Before we crashed here, we were all part of the same fleet – and someday, all the wandering clans will remember that. They will come when we call them. They will gather together, and we’ll form a city and build a civilisation again.”

“Won’t the Krell bomb it?” I asked, but cut him off before he could reply. “No. Not if we’re strong enough. Not if we stand and fight back.”

He smiled.

“I’m going to have my own ship,” I said. “I’m going to fly it, just like you. And then nobody in the clan will be able to make fun of me, because I’ll be famous.”

“Is that… is that why you want to be a pilot?”

“They can’t say you’re too small when you’re a pilot,” I said. “Nobody will think I’m weird, and I won’t get into trouble for fighting, because my job will be fighting. They won’t call me names, and everyone will love me.”

Like they love you.

That made my father hug me, for some stupid reason, even though I was just telling the truth. But I hugged him back, because parents like stuff like that. Besides, it did feel good to have someone to hold. Maybe I shouldn’t have left Bloodletter behind.

Father’s breath caught, and I thought he might be crying, but it wasn’t that. “Spensa!” he said, turning me again. “Look!” He pointed toward the sky. Again, I was struck by it.

So BIG.

Father was pointing at something specific. I squinted, noting that a section of the debris field was darker. No, not darker… was it missing? A hole in the sky?

In that moment, I looked out into infinity. I found myself trembling as if a billion meteors had hit nearby. I could see space itself, with little pinpricks of white in it, different from the enormous lights shining to illuminate the surface. The pinpricks sparkled, and seemed so, so far away.

“What are those lights?” I whispered.

“Stars,” he said. “We used to live out there. I fly up near the debris, but I’ve almost never seen through it. There are too many layers. Once in a while, you get a glimpse, though – and I’ve always wondered if I could get through.”

There was awe in his voice, a tone I didn’t think I’d ever heard from him before.

“Is that why you fly?” I asked.

My father didn’t seem to care about the praise the other members of the clan gave him. Strangely, he seemed embarrassed by it, and talked about just wanting to get back into his ship. I never understood it. Wasn’t the way everyone treated you the point of becoming a pilot? Stupid Rodge McCaffrey said it was.

My father drew my attention back to the hole in the sky. “Our real home,” he whispered. “That’s where we belong, not in those caverns. The kids who make fun of you, they’re trapped on this rock. Their heads are heads of rock, their hearts set upon rock. Set your sights on something higher. Something more grand.”

The debris shifted, and the hole shrank, until all I could see was a single star, brighter than the others.

“Claim the stars, Spensa,” he said.

The debris finally covered up the hole, but I remembered how it had looked. I was going to be a starfighter someday. I would fly up there and see those stars again. I just hoped my father would leave some Krell for me to fight when I –

I squinted as something flashed in the sky. A distant piece of debris, burning up as it entered the atmosphere.

Then another fell, and another. Then dozens.

My father frowned and reached for his radio – a super-advanced piece of technology that was given only to pilots. He lifted the blocky device to his mouth. “This is Chaser,” he said. “I’m on the surface. I see a debris fall at heading 605 from Alta.”

“We’ve spotted it already, Chaser,” a female voice said over the radio. “Radar reports are coming in now, and… Scud. We’ve got Krell.”

“What cavern are they headed for?” my father asked. “Their heading is… Chaser, they’re heading this way. They’re flying straight for Igneous. Stars help us. They have located the base!”

My father lowered his radio.

“Large Krell breach sighted,” the woman’s voice said through the radio. “Everyone, this is an emergency. An extremely large group of Krell have breached the debris field. All fighters report in. They’re coming for Alta!”

My father looked at me, then took my arm. “Let’s get you back.”

“They need you! You’ve got to go fight!” “I have to get you to – ”

“I can get back myself. It was a straight trip through those tunnels.”

My father glanced back toward the debris. “Chaser!” a new voice said over the radio. “Chaser, you there?”

“Mongrel?” my father said, flipping a switch and raising his radio. “I’m up on the surface.”

“You need to talk some sense into Banks and Swing. They’re saying we need to flee.”

My father cursed under his breath, flipping another switch on the radio. A voice came through. “- aren’t ready for a head-on fight yet. We’ll be ruined.”

“No,” another woman said. “We have to stand and fight.” A dozen voices started talking at once.

“Ironsides is right,” my father said into the line, and – remarkably – they all grew quiet.

“If we let them bomb Igneous, then we lose the Apparatus,” my father said. “We lose the manufactories. We lose everything. If we ever want to have a civilisation again, a world again, we have to stand here!”

I waited quiet, breathless, hoping he would be too distracted to send me away. I trembled at the idea of a fight, but I still wanted to watch it.

“We fight,” the woman said.

“We fight,” said Mongrel, the man who had spoken earlier. I knew that name; he was my father’s wingmate. “Hot rocks, this is a good one. I’m going to beat you into the sky, Chaser! Just you watch how many I bring down!”

The man sounded eager, maybe a little too excited, to be heading into battle. I liked him immediately.

My father debated only a moment before pulling off his bracelet light-line and stuffing it into my hands. “Promise you’ll go back straightaway.”

“I promise.” “Don’t dally.” “I won’t.”

He raised his radio. “Yeah, Mongrel, we’ll see about that. I’m running for Alta now. Chaser out.”

He dashed across the dusty ground in the direction he’d pointed earlier. Then he stopped and turned back. He pulled off his pin and tossed it – like a glittering fragment of a star – to me before continuing his run toward the hidden base.

I, of course, immediately broke my promise. I climbed back into the crack but hid there and watched until I saw the starfighters leave Alta and streak toward the sky. I squinted and picked out the dark Krell ships swarming down toward them.

Finally, showing a rare moment of good judgment, I decided I’d better do what my father had told me. I used the light-line to lower myself into the cavern, where I recovered my backpack and headed into the tunnels. I figured if I hurried, I could get home in time to join my clan as we listened to the broadcast of the fight on our single, communal radio.

I was wrong, though. The hike was longer than I remembered, and I did manage to get lost. So I was wandering down there, imagining the glory of the awesome battle happening above, when my father famously broke ranks and fled from the enemy. His own flight shot him down in retribution. By the time I got back, the battle had been won, my father was gone.

And I’d been branded the daughter of a coward.

1

I stalked my enemy carefully through the cavern.

I’d taken off my boots so they wouldn’t squeak. I’d removed my socks so I wouldn’t slip. The rock under my feet was comfortably cool as I took another silent step forward.

This deep, the only light came from the faint glow of the worms on the ceiling, feeding off the moisture seeping through cracks. You had to sit for minutes in the darkness to adjust your eyes to that faint light.

Another quiver in the shadows. There, near those dark lumps that must be enemy fortifications. I froze in a crouching position, listening to my enemy scratch the rock as he moved. I imagined a Krell: A terrible alien with inhuman features, all tentacled and slobbery.

With a steady hand – agonizingly slow – I raised my rifle to my shoulder, held my breath, and fired.

A squeal of pain was my reward.

Yes!

I patted my wrist, activating my light-line – the very one my father had given me. It sprang to life with a reddish-orange glow, blinding me for a moment.

Then I rushed forward to claim my prize: One dead rat, speared straight through.

In the light, shadows I’d imagined as enemy fortifications revealed themselves as rocks. My “enemy” was a plump rat, and my “rifle” was a makeshift speargun. Nine years had passed since that fateful day when I’d climbed to the surface with my father, but my imagination was as strong as ever. It helped relieve the monotony to pretend I was doing something more exciting than hunting rats.

I held up the dead rodent by its tail. “Thus you know the fury of my anger, fell beast.”

It turns out that strange little girls grow up to be strange young women. But I figured it was good to practice my taunts for when I really fought the Krell. Gran-Gran taught that a great warrior knew how to make a great boast to drive fear and uncertainty into the hearts of her enemies.

And who knew for sure what the Krell looked like? I’d always imagined them as having tentacle faces, but maybe they looked like rats. I grinned at that idea, and tucked my prize away into my sack. That was eight so far – not a bad haul.

It was probably time to turn back. The bracelet that housed my light-line had a little clock next to its power indicator, and I needed to return to Igneous before I missed too much of the school day. I slung my sack over my shoulder, picked up my speargun – which I’d fashioned from salvaged parts I’d found in the caverns – and started the hike back home.

I climbed up through cavern after cavern, following notes and maps I’d made in my small notebook. A part of me was sad to leave these silent caverns behind. They reminded me of my father, and though I rarely dared go up – near the surface – I liked it down here. I liked how… empty it all was. Nobody to stare at me, nobody to whisper insults until I was forced to defend my family honour by burying a fist in their stupid face.

I stopped at a familiar intersection where ancient metal broke the worn stone of the left wall: One of the enormous ancient tubes that moved water between the caverns, cleansing it and using it to cool machinery. A seam dripped water into a bucket I’d left, and it was half full, so I took a long drink. Cool and refreshing, with a tinge of something metallic.

I poured the rest into my canteen, then replaced the bucket and moved on. I could hear distant thrumming, and my path led that direction. To my right, the same pipe occasionally peeked from the stone. Eventually, I approached a break in the stone on my left, one that light poured through.

I stepped up and looked out onto Igneous. My home cavern, and the largest of the underground cities that made up the Defiant League. My perch was high, providing me with a stunning view of a large cave filled with boxy apartments, built like cubes splitting off one another.

My father’s dream had come true. Dozens of clans had gathered and colonised this one shared cavern. We were still divided in some ways – for example, I went to school only with people from my old clan – but we viewed ourselves as one. A single nation of Defiants.

Towering over the apartments of Igneous was the Apparatus – ancient forges, refineries, and manufactories that pumped molten rock from below, then created the parts to build starfighters. It was amazing; it barely needed maintenance, and could build any parts we needed. It was also unique; though other caverns had been found with machinery that provided heat, electricity, or filtered water, only this one could be used for complex manufacturing.

Heat poured through the crack, making my forehead bead with sweat. Igneous was a sweltering place, always hot and humid, with all those refineries, factories, and algae vats. And though it was relatively well lit, it somehow always felt gloomy inside, the orange-red light from the refineries overwhelming the lights of streets and buildings.

I couldn’t get in through this crack, not unless I wanted to lower myself on my light-line – which wouldn’t be a terribly bright idea. Instead I walked over to an old maintenance locker I’d discovered on the wall here. Its hatch looked – at first glance – like just another section of the stone tunnel. I popped it open, revealing my few secret possessions: Some parts for my speargun, my spare canteen, and my father’s old pilot’s pin. I rubbed that for good luck, then placed my light-line, map notebook, and speargun into the locker.

I retrieved a crude stone spear, clicked the hatch closed, then slung my sack over my shoulder again. Eight rats could be surprisingly awkward to carry, particularly when – even at seventeen – you had a body that refused to grow beyond five feet.

I hiked down to the normal entrance into the cavern. Two soldiers from the ground troop corps (which barely ever did any real fighting) guarded the way in. I knew them both by their first names, but they still made me stand to the side as they pretended to call for authorization for me to enter. Really, they just liked making me wait.

Every day. Every scudding day.

Eventually, Aluko stepped over and began looking through my sack with a suspicious eye.

“What kind of contraband do you expect I’m bringing into the city?” I asked him. “Pebbles? Moss? Maybe some rocks that insulted your mother?”

He didn’t respond, though he did eye my spear as if wondering how I’d managed to catch eight rats with such a simple weapon. Well, let him wonder.

Finally, he tossed the sack back to me. “On your way, coward.”

Strength. I lifted my chin. “Someday,” I said, “you will hear my name, and tears of gratitude will spring to your eyes as you think of how lucky you are to have once assisted the daughter of Chaser.”

“I’d rather just forget I ever knew you. On your way.”

I held my head high and walked into Igneous, then made my way toward the Glorious Rises of Industry, the name of my home neighbourhood. I’d arrived at shift change, and passed workers in jumpsuits of a variety of colours, each marking their place in the great machine that kept the Defiant League – and the war against the Krell – functioning. Sanitation workers, maintenance techs, algae vat specialists.

No pilots, of course. Off-duty pilots stayed in the deep caverns on reserve, while the on-duty pilots lived in Alta, the very base my father had died protecting. The base where I would live, once I took the test tomorrow and became a pilot myself.

I passed under a large metal statue of the First Citizens: A group of people holding tools and reaching toward the sky in defiant poses, streaks representing ships shooting out behind them. Though it was supposed to represent those who had fought at the Battle of Alta, my father wasn’t among them.

The next turn took me to our apartment, one of many cubes sprouting from a central square. Ours was small, but big enough for three people, particularly since I had a habit of spending days at a time out in the caverns, hunting and exploring.

My mother wasn’t home, but I found Gran-Gran on the roof, rolling algae wraps to sell at our cart. That was how we made a living without an official job. Real work was forbidden to my mother because of my father, and Gran-Gran… well, Gran-Gran was special. She spurned regular Defiant jobs as a matter of principle.

Gran-Gran looked up, hearing me. She was practically blind, and had been from birth, with a clubfoot and sticklike arms. But she was strong. So strong.

“Oooh,” she said. “That sounds like Spensa! How many did you get today?”

“Eight!” I dumped my spoils before her. “And several are particularly juicy.”

“Sit, sit,” Gran-Gran said, pushing aside the mat filled with wraps. “Let’s get these cleaned and cooking! If we hurry, we can have them ready for your mother to sell today.”

I probably should have gone off to class – Gran-Gran had forgotten again – but really, what was the point? These last few days before graduation, students were just getting lectures on the various jobs one could do in the cavern. I had already chosen what I’d be. The test to become a pilot was supposed to be hard, but Rodge and I had been studying for ten years. I was confident. So why did I need to hear about how great it was to be an algae vat worker or whatever?

Besides, as I needed to spend time hunting, I missed a lot of classes, so I wasn’t suited to any other jobs. I made sure to attend the classes that had to do with flying – ship layouts and repair, mathematics, war history. Important things like that. Any other class I managed to make was just a bonus.

I settled down and helped Gran-Gran skin and gut the rats. She was as clean and efficient as ever as she worked by touch.

“Who,” she asked, head bowed, eyes mostly closed, “do you want to hear about today?”

“Beowulf!”

“Ah, the King of the Geats, is it? Not Leif Eriksson? He was your father’s favourite.”

“Did he kill a dragon?”

“He discovered a new world.”

“With dragons?”

Gran-Gran chuckled. “A feathered serpent, by some legends, but I have no story of them fighting. Now, Beowulf, he was a mighty man. He was your ancestor, you know. It wasn’t until he was old that he slew the dragon; first he needed to make his name by fighting monsters.”

I worked quietly with my knife, cleaning the rats, then slicing the meat and tossing it into a pot to be stewed. Most people in the city lived on algae paste. And most real meat – from cattle or pigs raised in caverns with special lighting and environmental equipment – was far too rare for everyday eating. So they’d pay for rats.

I loved the way Gran-Gran told stories. Her voice grew soft when the monsters hissed and bold when the heroes boasted. She worked with nimble fingers as she spun the tale of the ancient Viking hero, who came to aid the Danes in their time of need. A warrior, not afraid to speak of his accomplishments. A hero everybody loved; one who fought bravely, even against a larger and mightier foe.

“And when the monster had slunk away to die,” Gran-Gran said, “the hero, he held aloft Grendel’s entire arm and shoulder as a grisly trophy. He’d made good on his boasts and had avenged the blood of the fallen, proving himself with strength and valor.”

Clinking sounded from below, in our apartment. My mother was back. I ignored it for now. “He ripped the arm free,” I said, “with his hands?”

“He was strong,” Gran-Gran said, “and a warrior true. But he was of the oldenfolk, who fought with hands and sword.” She leaned forward. “You will fight with nimbleness of both hand and wit. With a starship to pilot, you won’t need to be ripping any arms off. Next time, let me tell you of Sun Tzu, the greatest general of all time. He will teach you tactics. He was your ancestor, you know.”

I smiled: Gran-Gran often told me of Sun Tzu. Her memory could be fickle – she remembered every story, every history, and every genealogy, but sometimes she forgot what she’d said and when.

“I prefer Genghis Khan,” I said.

“A tyrant and a monster,” Gran-Gran said, “though, yes, there is much to learn from the Great Khan’s life. But have I ever told you of Queen Boudicca, defiant rebel against the Romans? She was your – ”

“Ancestor?” Mother finished, climbing the ladder outside the building. “She was a British Celt, Mother. Beowulf was Swedish, Genghis Khan Mongolian, and Sun Tzu Chinese. And they’re all supposedly my daughter’s ancestors?”

“All of Old Earth is our heritage!” Gran-Gran said. “You,

Spensa, are one in a line of warriors stretching back millennia, a true line to Old Earth and its finest blood.”

Mother rolled her eyes. She was everything I wasn’t – tall, beautiful, calm. She noted the rats but then looked at me with arms folded. “She might have the blood of warriors, but today, she’s late for class.”

“She’s in class,” Gran-Gran said. “The important one.”

I stood up, wiping my hands on a rag. I knew how Beowulf would face monsters and dragons… but how would he face his mother on a day when he was supposed to be in school? I settled on a noncommittal shrug.

Mother eyed me. “He died, you know,” she said. “Beowulf died fighting that dragon.”

“He fought to his last ounce of strength!” Gran-Gran said. “He defeated the beast, though it cost him his life. And he brought untold peace and prosperity to his people! All the greatest warriors fight for peace, Spensa. Remember that.”

“At the very least,” Mother said, “they fight for irony.” She glanced again at the rats. “Thanks. But get going. Don’t you have the pilot test tomorrow?”

“I’m ready for the test,” I said. “Today is just learning things I don’t need to know.”

Mother gave me an unyielding stare. Every great warrior knew when they were bested. I gave Gran-Gran a hug and whispered, “Thank you.”

“Soul of a warrior,” Gran-Gran whispered back. “They’re all looking to be gears in this grand machine they have created. My little warrior, don’t be ashamed if you, instead, are too sharp to be a gear.”

I smiled, then went and quickly washed up before heading off to what would, I hoped, be my last day of class.

2

“Why don’t you tell us what you do each day in the Sanitation Corps, Citizen Alfir?” Mrs Vmeer, our Work Studies instructor, nodded encouragingly at the man who stood at the front of the classroom.

This Citizen Alfir wasn’t what I’d imagine a sanitation worker to be. Though he wore the jumpsuit and carried a pair of rubber gloves hooked to his belt, he was actually handsome: Square jaw, burly arms, chest hair peeking out from above his tight jumpsuit collar.

I could almost imagine him as Beowulf. Until he spoke. “Well, we mostly fix clogs in the system,” he said. “Clearing what we call black water – that’s mostly human waste – so it can flow back to processing, where the Apparatus reclaims it and harvests both water and useful minerals.”

“Sounds perfect for you,” Dia whispered, leaning toward me. “Cleaning waste? A step up from coward’s daughter.”

I couldn’t punch her, unfortunately. Not only was she Mrs Vmeer’s daughter, I was already on notice for fighting. Another write-up would keep me from taking the tests, which was stupid. Didn’t they want their pilots to be great fighters? How were we supposed to practice?

We sat on the floor in a small room. No desks for us today; those had been requisitioned by another instructor. I felt like a four-year-old being read a story.

“It might not sound glorious,” Alfir said. “But it’s a vital part of the Defiant war effort. Without the Sanitation Corps, none of us would have water, and we’d quickly grow sick from contamination. The war against the Krell would be lost in a day or two. We’re in some ways the most important part of the system.”

Though I’d missed some of these lectures, I’d heard enough of them. The Ventilation Corps workers earlier in the week had said much the same thing about their job. And the construction workers from the day before. And the forge workers, the cleaning staff, and the cooks. They all had practically the same speech.

Every person is some important gear or cog, I thought, anticipating what he’d say next.

“Every job in the cavern is a vital part of the machine that keeps us alive,” Alfir said. “We can’t all be pilots, but no job is more important than another.”

It’s essential, I thought, that you learn your place and do your job well. Precision is more important than grandstanding.

“To join us, you have to be able to follow instructions,” the man said. “You have to be willing to do your part, no matter how insignificant it may seem. Remember, obedience is defiance.”

I got it, and to an extent, agreed with him. Pilots wouldn’t get far in the war without water, or food, or sanitation.

Taking jobs like these still felt like settling. Where was the spark, the energy? We were supposed to be Defiant. We were warriors.

The class just clapped politely when Citizen Alfir finished. Outside the window, more workers walked in lines beneath statues with straight, geometric shapes.

Sometimes we seemed far less a machine of war than a clock for timing how long shifts lasted.

With the presentation over, the students stood up for a break. I strode away before Dia could make another wisecrack. The girl had been trying to goad me into trouble all week.

Instead, I approached a lanky boy with red hair at the back of the room. He’d immediately opened a book to read once the lecture was done.

“Rodge,” I said. “Rigmarole!”

His nickname – the callsign we’d chosen for him to take once he became a pilot – made him look up. “Spensa! When did you get here?”

“Middle of the lecture. You didn’t see me come in?”

“I was going through flight schematics lists in my head.

Scud. Only one day left. Aren’t you nervous?”

“Of course I’m not nervous. Why would I be nervous? I got this down.”

“Not sure I do.” Rodge glanced back at his textbook.

“Are you kidding? You know basically everything, Rig.” “You should probably just call me Rodge. I mean, we haven’t

earned callsigns yet. Not unless we pass the test.” “Which we will totally do.”

“But what if I haven’t studied the right material?”

“Five basic turn maneuvers?”

“The reverse switchback,” he said immediately, “Ahlstrom loop, the twin shuffle, overwing twist, and the Imban turn.”

“Average seconds to blackout at F-G?” “Fifteen and a half.”

“Engine type on a Poco interceptor?” “Which design?”

“Current interceptor.”

“AG-113-2. Yes, I know that, Spensa – but what if those questions aren’t on the test? What if it’s something we didn’t study?”

I felt, at his words, just the faintest seed of doubt. While we’d done practice tests, the actual contents of the pilot’s test changed every year. There were always questions about engine types and maneuvers, but technically, any part of our schooling could be included.

I’d missed a lot of classes, but I knew I shouldn’t worry.

Beowulf wouldn’t worry. Confidence was the soul of heroism. “I’m going to ace that test, Rig,” I said. “We two, we’re going

to be the best pilots in the DDF. We’ll fight so well, the Krell will raise lamentations to the sky, like smoke above a pyre, crying in desperation at our passing!”

Rig cocked his head. “A bit much?” I asked.

“Where do you come up with these things?” “Sounds like something Beowulf might say.” “Who?”

OK, so maybe he didn’t know everything.

He settled back down to study, and I probably should have joined him. But there was a part of me that was fed up with studying, with trying to cram things into my brain. I wanted the challenge to just arrive.

We had one more lecture today, unfortunately. I listened to

the other dozen or so students chatter together, but I wasn’t in a mood to put up with their stupidity. Instead, I found myself pacing like a caged animal, until I noticed Mrs Vmeer walking toward me with Alfir, the sanitation guy.

She wore a bright green skirt, but the silvery cadet’s pin on her blouse was the real mark of her achievement. It meant she’d passed the pilot’s test herself. She must have washed out in flight school – otherwise she’d have a golden pin – but washing out wasn’t uncommon. And down here in Igneous, even a cadet’s pin was a mark of great accomplishment. Mrs Vmeer had special clothing and food requisition privileges.

She wasn’t a bad teacher – she didn’t treat me much differently from the other students, and she hardly ever scowled at me. I kind of liked her, even if her daughter was a creature of distilled darkness, worthy only of being slain so her corpse could be used to make potions.

“Spensa,” Mrs Vmeer said. “Citizen Alfir wanted to speak with you.”

I braced myself for questions about my father. Everyone always wanted to ask about him. What was it like to live as the daughter of a coward? Did I wish I could hide from it? Did I ever consider changing my surname? People who thought they were being empathetic always asked questions like those.

“I hear,” Alfir said, “that you’re quite the explorer.”

I opened my mouth to spit back a retort, then bit it off. What?

“You go out in the caves,” he continued, “hunting?” “Um, yes,” I said. “Rats.”

“We have need of people like you,” Alfir said. “In sanitation?”

“A lot of the machinery we service runs through far-off caverns. We make expeditions to them now and then, and having someone in the corps who is familiar with caverns could be a boon. If you want a job, I’m offering one.”

A job. In sanitation?

“I’m going to be a pilot,” I blurted out.

“The pilot’s test is hard,” Alfir said, glancing at our teacher. “Not many pass it. I’m offering you a guaranteed place with us. You sure you don’t want to consider it?”

“No, thank you.”

Alfir shrugged and walked off. Mrs Vmeer studied me for a moment, then shook her head and walked away to welcome the next lecturer – someone who was going to tell us about the Algae Vat Corps.

I backed up against the wall, folding my arms. Mrs Vmeer knew I was going to be a pilot. Why would she think I’d accept such an offer? Alfir couldn’t have known about me without her saying something to him, so… what was up?

“They’re not going to let you be a pilot,” said a voice beside me.

I glanced and saw – belatedly – that I’d happened to walk over by Dia. The dark-haired girl sat on the floor, back to the wall. Why wasn’t she chatting with the others?

“They don’t have a choice,” I said to her. “Anyone can take the pilot’s test.”

“Anyone can take it,” Dia said. “But they decide who passes, and it’s not always fair. The children of First Citizens get in automatically.”

Everyone knew that. They deserved it, as their parents had fought at the Battle of Alta. Technically, so had my father – but I wasn’t counting on that to help me.

Still, I’d always been told that everyone found their place, and rank – or status – didn’t matter, so long as you showed aptitude. The DDF didn’t care who you were, so long as you could fly.

“I know they won’t count me as a daughter of a First,” I said. “But if I pass, I get in. Just like anyone else.”

“That’s the thing, spaz. You won’t pass, no matter what. I heard my parents talking about it last night. Admiral Ironsides gave orders to deny you. You don’t really think they’d let the daughter of Chaser fly for the DDF, do you?”

“Liar.” I felt my face grow cold with anger. She was trying to taunt me again, get me to throw a fit.

Dia shrugged. “You’ll see. It doesn’t matter to me – my father already got me a job in the Administration Corps.”

I hesitated. This wasn’t like her usual insults. It didn’t have the same vicious bite, the same sense of amused taunting. She… she really seemed like she didn’t care whether I believed her or not.

I stalked across the room to where Mrs Vmeer was speaking with the woman from the Algae Vat Corps.

“We need to talk,” I told her. “Just a moment, Spensa.”

I stood there, intruding on their conversation, arms folded, until finally Mrs Vmeer sighed, then pulled me to the side. “What is it, child?” she asked. “Have you reconsidered Citizen Alfir’s kind offer?”

“Did the Admiral herself order that I’m not to pass the pilot’s test?”

Mrs Vmeer narrowed her eyes, then turned and glanced toward her daughter.

“Is it true?” I asked.

“Spensa,” Vmeer said, looking back at me. “You have to understand, this is a very delicate issue. Your father’s reputation is – ”

“Is it true?”

Mrs Vmeer drew her lips into a line and didn’t answer.

“Is it all lies, then?” I asked. “The talk of equality, and of only skill mattering? Of finding your right place and serving there?”

“It’s complicated,” Vmeer said. She lowered her voice. “Look, why don’t you skip the test tomorrow to save everyone the embarrassment? Come to me, and we’ll talk about what might work for you. If not sanitation, perhaps ground troops?”

“So I can stand all day on guard duty?” I said, my voice growing louder. “I need to fly. I need to prove myself!”

Mrs Vmeer sighed, then shook her head. “I’m sorry, Spensa.

But this was never going to be. I wish one of your teachers had been brave enough to disabuse you of the notion when you were younger.”

In that moment everything came crashing down around me. A daydreamed future. A carefully imagined escape from my life of ridicule.

Lies. Lies that a part of me had suspected. Of course they weren’t going to let me pass the test. Of course I was too much of an embarrassment to let fly.

I wanted to rage. I wanted to hit someone, break something, scream until my lungs bled.

Instead, I strode from the room, away from the laughing eyes of the other students.

Excerpt copyright © 2018 by Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC. Published by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.