The history of elephants – from gigantic woolly mammoths through to modern forest-dwelling pachyderms – is more complicated than we thought. An analysis of modern and ancient elephant genomes shows that interbreeding and hybridisation was an important aspect of elephant evolution.

Portion of a mural depicting a herd of mammoths walking near the Somme River in France (1916). Illustration: Charles R. Knight (American Museum of Natural History/Public Domain)

New research published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that ancient elephants were very much the product of interbreeding between species. Elephants – both those from the ancient past and those living today – were shaped by this mating practice, but it isn’t something the two remaining species of elephants are into any more.

Interbreeding among closely related mammalian species is fairly common. Good examples today are brown bears and polar bears, Sumatran and Bornean orangutans, and Eurasian gold jackals and grey wolves. Evolution does a pretty good job of creating advantageous new traits using the powers of random mutation, but there’s nothing quite like interbreeding, where the traits from two different species get intermixed. And in fact, our ancient ancestors were into the whole interbreeding thing, too, with anatomically modern humans getting it on with Neanderthals and Denisovans. So in a way, we’re also a kind of hybrid species.

Elephants, as the new study points out, share a similar past – though to an extent not previously appreciated.

“Interbreeding may help explain why mammoths were so successful over such diverse environments and for such a long time,” said Hendrik Poinar, McMaster University evolutionary geneticist and study co-author, in a statement. “Importantly this genomic data also tells us that biology is messy and that evolution doesn’t happen in an organised, linear fashion.”

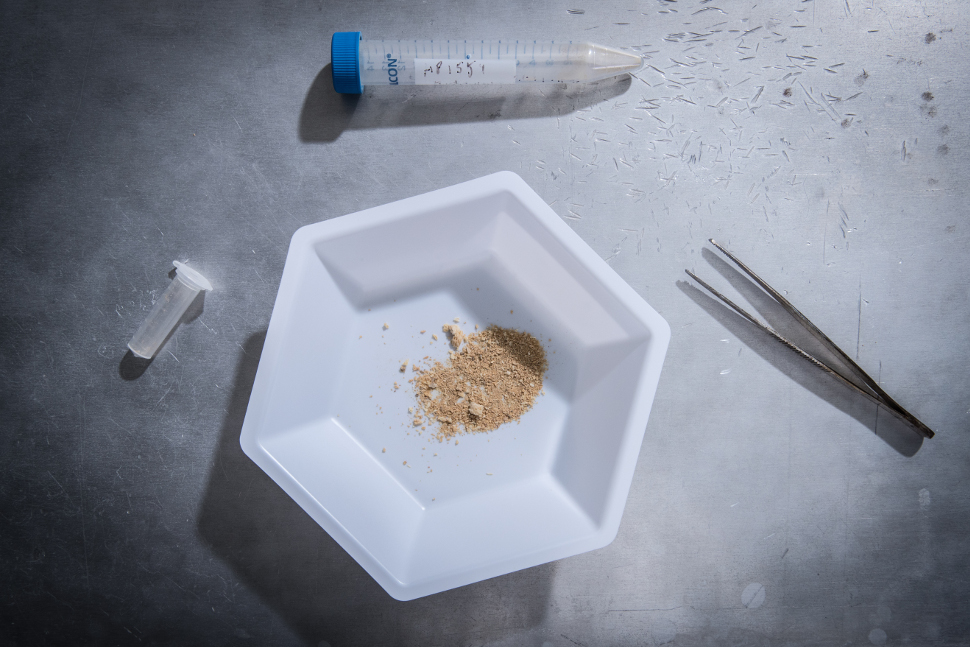

Crushed woolly mammoth bone used for DNA extraction. Image: JD Howell (McMaster University)

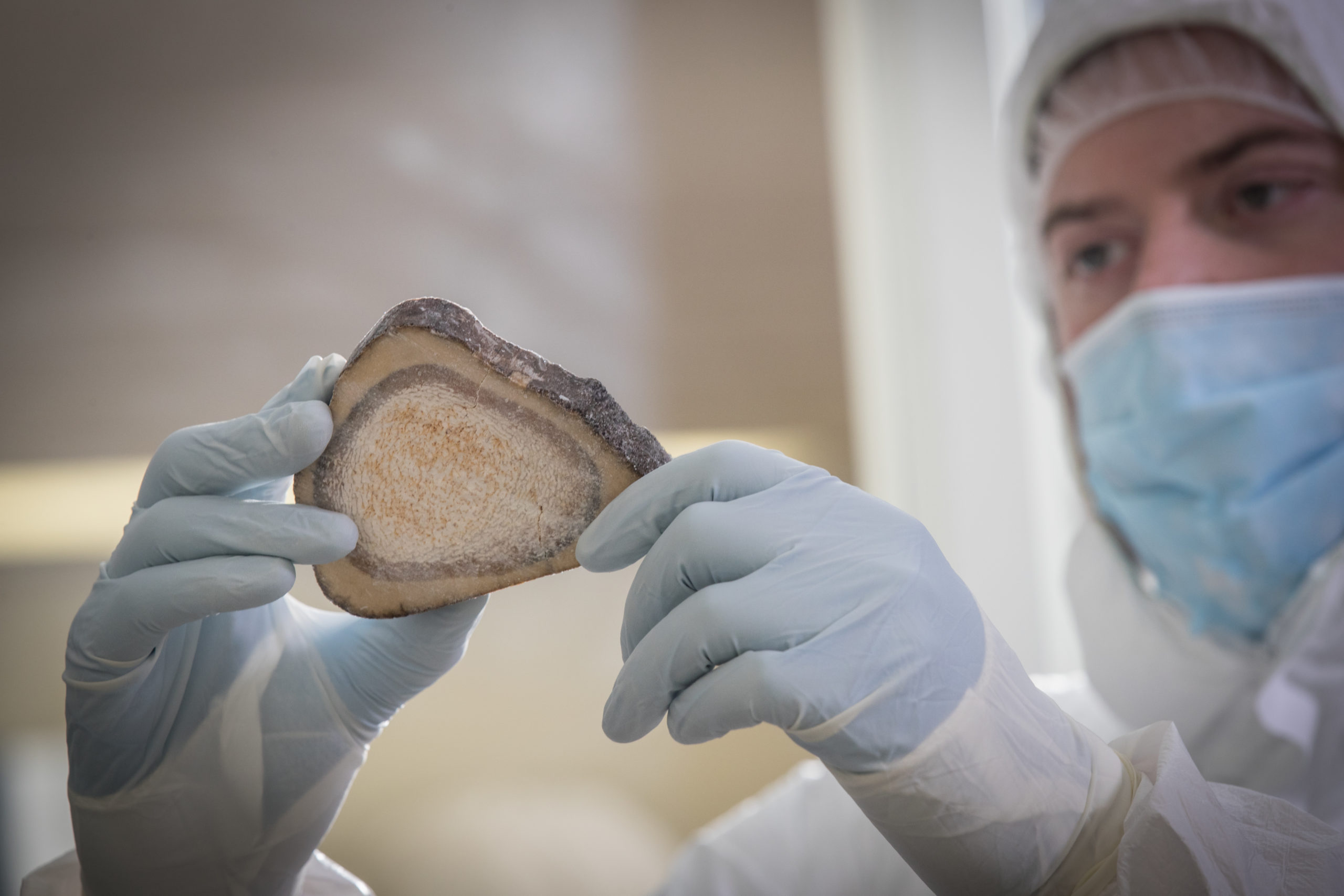

For the study, lead author Eleftheria Palkopoulou from the Harvard Medical School, along with colleagues from McMaster, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Uppsala University, and the University of Potsdam, sequenced 14 genomes from several living and extinct elephant species, including multiple Woolly Mammoth genomes, a Columbian Mammoth genome (a scientific first), multiple Asian elephant genomes, a pair of African Forest elephant genomes, two Straight-tusked elephant genomes, two African Savanna elephant genomes, and, amazingly, a couple of American Mastodon genomes (which technically speaking aren’t elephants). Incredibly, the researchers were able to generate high-quality genomes from samples that haven’t been frozen and are more than 100,000 years old; gene sequences were extracted from bits of bone and teeth found in well-preserved remains.

“The combined analysis of genome-wide data from all these ancient elephants and mastodons has raised the curtain on elephant population history, revealing complexity that we were simply not aware of before,” said Poinar.

For example, the researchers learned that the ancient Straight-tusked elephant – an extinct species that stomped around Europe between 780,000 and 50,000 years ago – was a hybrid species, with portions of its DNA being similar to an ancient African elephant, the Woolly Mammoth and Forest elephants, the latter of which are still around today. They also uncovered further evidence to support the suggestion that two species of mammoths – the Columbian and Woolly Mammoths – interbred. This idea was first proposed by Poinar in 2011. Despite their different habitats and sizes, these creatures likely ran into each other near glacial boundaries and in more temperate regions of North America. Indeed, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that these ancient elephants frequently bumped into each other; for a time, mammoths had a territory that extended from modern-day Portugal and Spain all the way to the US East Coast.

A cross-section of a woolly mammoth shin bone. Image: JD Howell (McMaster University)

The researchers also learned that the two still-living species of elephant, the Forest and Savanna elephants, diverged from a common ancestor about two million to five million years ago, but they have lived in near-complete isolation for the past 500,000 years. Despite living in neighbouring habitats, these elephants don’t like to mix.

“Observationally, people knew that Savanna and Forest elephants did not have much interbreeding. When they did, offspring wouldn’t survive well,” Rebekah Rogers, an evolutionary geneticist at Berkeley who wasn’t involved in the new study, told Gizmodo. “This paper tells us that the elephants weren’t sneaking around behind our backs or passing around genes at lower rates. The genetics suggest that the rates of successful interbreeding was very low.”

Rogers said the paper also tells us that what we view as big physical dissimilarities may not be such significant differences to the elephants.

“When we look at mammoths compared to [other] elephants we immediately notice their fur, their hump, and differences in their circulatory system,” she said. “This paper suggests that we can see that they interbred more successfully than African Savanna elephants and Forest elephants, which to us look so much alike.”

Rogers is particularly stoked that the researchers were able to obtain genetic sequence data for an elephant from Borneo. These are very small populations that have been isolated for quite some time, and the results of the new study match this reality by exposing their very low genetic diversity.

“This is a pretty cool study,” Vincent J. Lynch, an evolutionary geneticist from the University of Chicago who was not involved in the research, told Gizmodo. “The work is good and I don’t see any serious limitations or caveats. The phylogeny [the ancestral “family tree”] they report is well-supported.”

For Lynch, the most surprising aspect of the study was just how much ancestral hybridisation was going on in the history of elephants, particularly between Straight-tuskers and Woolly Mammoths. He also says the new study is a great example of open science.

“The African elephant genome was made public in 2005 and is only formally published with this paper,” he told Gizmodo. “That is 13 years in which we and other people have been able to use the African elephant genome in our own research. Old-school ways would have kept that genome behind a closed doors, with only a select few having access. By releasing the genome in 2005 it gives the community a chance to move science forward while these authors do the hard work of sequencing all these other elephant genomes for their study.”

Looking ahead, the researchers would like to explore how (and if) the intermingling of genetic traits may have been advantageous for elephant evolution, like an increased tolerance for hew habitats and climate change.

[PNAS]