So far, the New York City MTA’s “summer of hell” included a power failure that trapped train passengers in A/C-less car for two hours, a track fire that resulted in disastrous delays, and a train derailment caused by “improper maintenance.” Incredibly, some passengers have even been walking the tracks to escape stalled trains. Last Tuesday, the MTA dropped its new $US800 million proposal suggesting, among other things, hiring more personnel and a pilot program of adding standing-only cars to the L train. That funding has not yet been secured.

In the midst this prolonged nightmare, it’s hard not to flashback on Hurricane Sandy, which crippled the city’s subway lines and stranded millions of commuters. If the subway could apparently fall apart at a moment’s notice, with or without an unprecedented hurricane, what would happen if and when another Sandy hit? What steps has the MTA taken to gird itself against future weather catastrophes, in a world where climate change is expected to make many extreme weather events more likely? We spoke with the MTA and the contractors, risk-assessors and climate scientists the MTA has tapped since Sandy to try and figure out how it might save itself from a whole lifetime of hell.

Edgar Westerhof spent the hours before Hurricane Sandy cycling around lower Manhattan marveling at the MTA’s unpreparedness. As a professional risk-assessor with Dutch-based firm Arcadis, Westerhof was keenly aware of just how vulnerable the city’s ancient infrastructure was even without the threat of a once-in-a-lifetime storm. “They’re masterpieces of their time,” he said, of the city’s tunnels and bridges. “But that time was the ’40s, the ’50s, the ’60s.” To his surprise, the subway grates and entrances he passed on the night of Sandy appeared for the most part to be uncovered.

But the MTA was preparing, in its way, according to Klaus Jacobs. As a scientist at Columbia University, Jacobs had been warning the MTA of the risks posed by rising sea-levels (New York City has already experienced at least a foot of sea level rise since 1900) and other consequences of climate change for years. The MTA refused to listen, or cooperate — and so, in the early and mid 2000s, Jacobs sent his grad students into the subway to conduct guerilla barometric readings, measuring the elevation of the tunnels to determine which ones would flood. He sent the agency the results, which made clear that the MTA stood to lose unfathomable sums of money if it failed to reckon with the reality of global warming.

Damage on the New York City Subway’s Rockaway Line (A train). October 30, 2012. Photo: MTA New York City Transit / Leonard Wiggins

By the next time Jacobs came around, as part of the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority-funded ClimAID study on the effects of climate change on the state, the MTA was ready to listen, and eager to help. Jacobs’ ClimAID study, which looked at how NYC Transit could adapt to climate change, came out just a year before Sandy, and wound up saving the agency billions of dollars — in the 24 hours before the storm made landfall, the MTA sent workers down into the tunnels to rip out crucial control and signal systems ID’d by Jacobs’ team as the most vulnerable, reducing eventual average downtime from three weeks to one, according to Jacobs.

Still, that last-minute cram session couldn’t make up for years of inaction. “They had years before to do something, and didn’t,” Jacobs said. Ultimately Sandy wrecked eight subway tunnels, welcomed millions of gallons of corrosive seawater into the system (which in turn fried millions of dollars’ worth of equipment) and ensured at least a decade of headaches for New York City’s commuters. Crucial tunnels connecting Brooklyn to lower Manhattan were shut down, stranding millions of commuters (unless they wanted to brave the standstill traffic on the Williamsburg bridge, via one of the MTA’s packed buses); 457.20m of aboveground track were wiped out in the Rockaways; NJ Transit was shut down for nearly a month; and irreplaceable equipment was destroyed — as Jacobs points out, “you can’t go to Westinghouse or General Electric and say: give me a new one. [Some of this equipment] was not manufactured anymore.”

The subway had already suffered a handful of smaller-scale floods, each worse than the last: Hurricane Floyd, in 1999, caused only minor delays, but 2004’s Hurricane Frances led to significant ones, and stranded hundreds of commuters underground for hours. And in 2007, then-Governor Eliot Spitzer ordered an inquiry into the MTA’s flood problems after heavy rains led to what he called “a total outage of our mass transportation system” (according to that afternoon’s New York Times, the rainfall “delayed or disabled every one of the city’s subway lines”).

Employees from MTA New York City Transit worked to restore the South Ferry subway station after it was flooded by seawater during Hurricane Sandy. October 30, 2012 Photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority / Patrick Cashin.

But Sandy was perhaps the most expensive wake-up call in New York history. Jacobs and his ClimAID team had “no inkling” that their findings would become relevant within twelve months; likewise we have no way of knowing when the “next” Sandy might hit. Still, as FEMA and US Army crews dewatered the flooded tunnels, NYC Transit turned its attention to the future.

According to MTA spokesman Kevin Ortiz, NYC transit formed a specialised Recovery and Resiliency division in the wake of Sandy. This division was tasked both with repairing the immediate damage and hardening the system against future flooding, Ortiz says. According to Ortiz, the long-term cost of the project has been “identified” as $US4.5 billion. One of the division’s first tasks was to assess the impact of another category II storm (like Sandy), plus (to be safe) an extra three feet of water. Dozens of experts — among them Westerhof, at Arcadis, and Jacobs — helped the MTA determine which of its assets were most at risk; according to Jacobs, it was determined that 3,600 flood-zone subway openings would need to be plugged — some with permanent, remotely-deployable steel doors, some with temporary materials. In all, the MTA has designed at least a dozen site-specific flood-protection measures to ease the burden of the next major hurricane.

The MTA also turned its attention to repairing and hardening the more than half-dozen tunnels ruinously water-logged by Sandy. So far, Ortiz says, work has been completed on three tunnels, is still in progress on four tunnels and is yet to begin on two tunnels: the Rutgers Tube (which connects Manhattan and Brooklyn on the F line) and, of course, the Canarsie Tunnel, which connects Brooklyn to Manhattan via the L line. Repairs — and the L train’s controversial shutdown — will begin in April 2019.

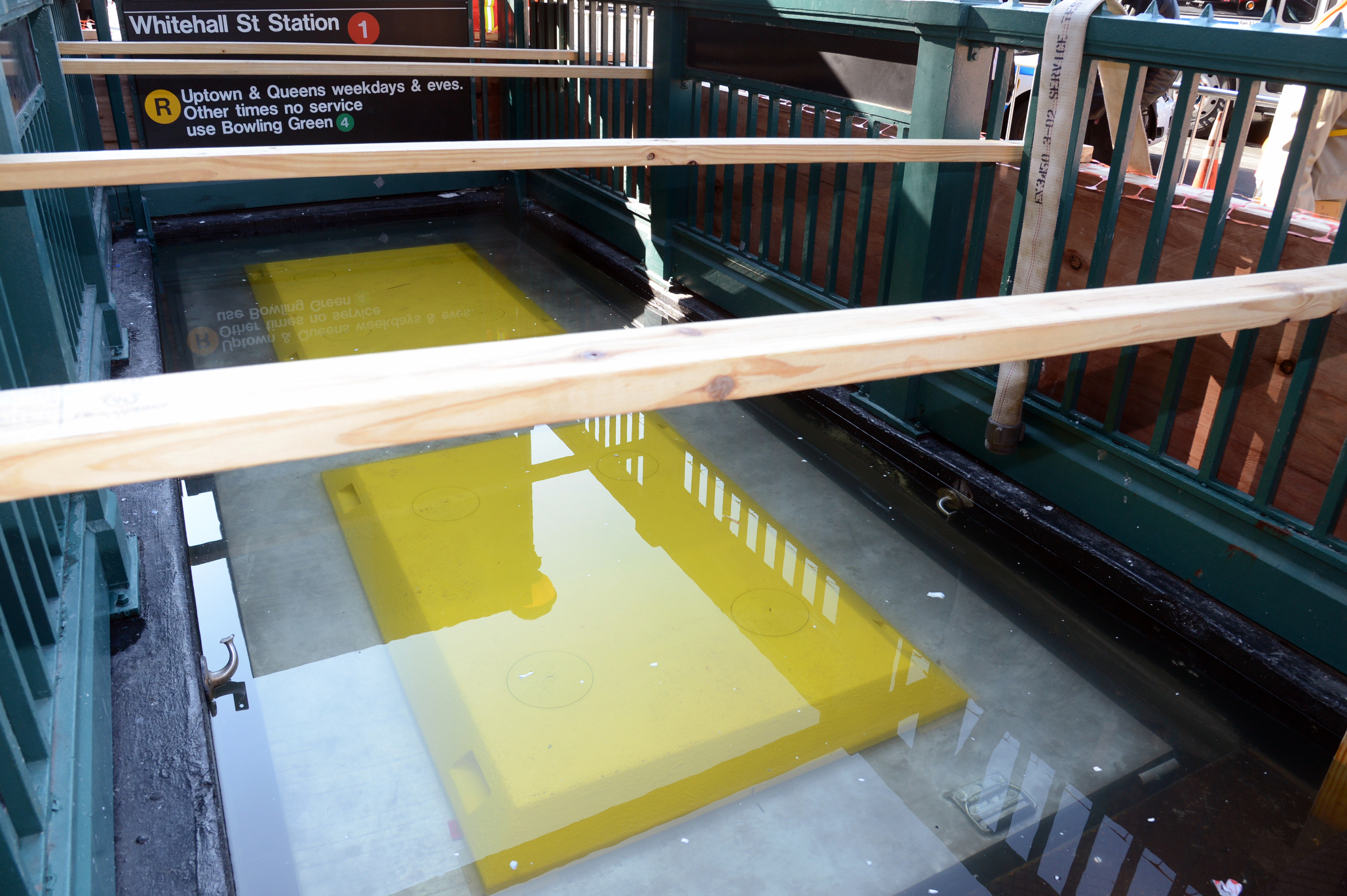

Flood Control Cover at the Whitehall St. Station. Tue., October 29, 2013. Photo: Marc A. Hermann / MTA New York City Transit

To repair and floodproof these tunnels NYC Transit has awarded 63 contracts so far, 37 of which have been completed, according to Ortiz. (20 more contracts need to be awarded by the end of the year, and an additional $US200 million will need to be awarded next year, according to Ortiz).

One of these contracts went to ILC-Dover, among the handful of firms contracted to come up with retrofitted coverings for the thousands of varyingly-sized openings (stairways, grates, manholes, elevators, and escalators, etc.) which need to be plugged. MTA was looking for coverings which could be installed quickly (and removed easily, after the storm), and which could be stored on-site, as the MTA doesn’t want to have to haul out its flood supplies from a Brooklyn or Jersey warehouse in the hectic hours right before a storm.

ILC-Dover addressed this issue with its “point of storage” technology. Right now twenty-four lower Manhattan subway entrances contain, opposite the first step, a small cabinet containing ILC-Dover’s “stairwell protection technology” — “like a windowshade, but flat,” said Brad Walters, the firm’s VP. The stairwell covers are made of fabric, as opposed to steel, and in case of a Sandy-style hurricane can be unwound and locked in place in about fifteen minutes, by someone with only fifteen minutes’ training. Forty-four more are on the way, for a total of 68; if and when the next Sandy does arrive, they will leak “less than a little rainshower,” according to Walters. When asked how long this would take, Walters did not provide a timeline.

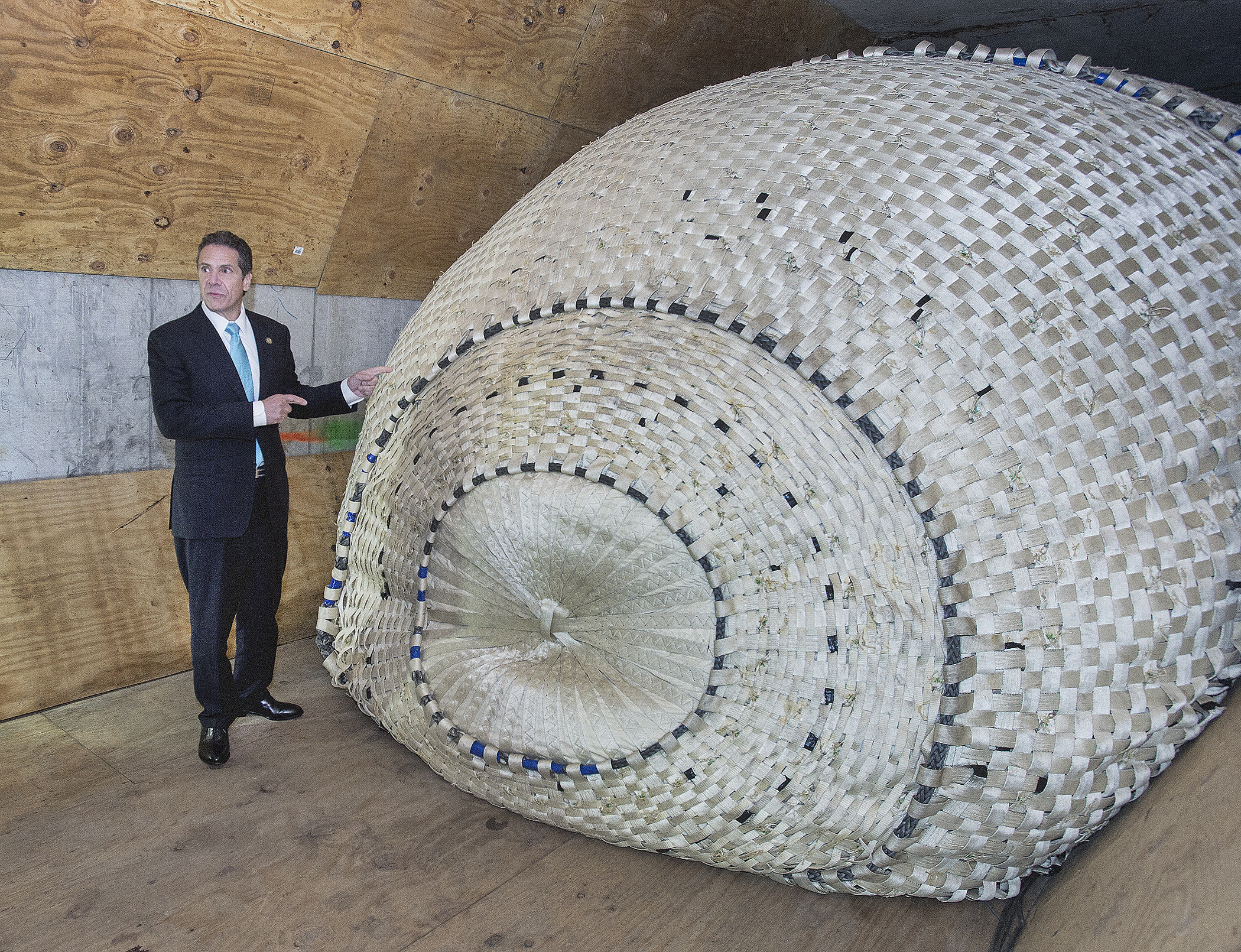

Governor Cuomo looks at a tunnel plug under South Ferry Station. October 29, 2013. Photo: MTA / Patrick Cashin

In addition to the grate and entrance coverings, these contracts cover marine doors (“they look like big bank vaults,” Jacobs said), massive plugs, the 12.19m floodwall erected along Jamaica Bay in the Rockaways (where much of the A line was washed out during Sandy, and the new pumps at the recently-reopened South Ferry station, which according to Ortiz are capable of pumping out 5,678l of water per minute.

It’s not clear to what extent these improvements would help the city if another Sandy struck tomorrow. “Designing something, implementing something in New York City — it’s the most complicated retrofit you could think of,” said Westerhof. The subway is, in his words, “a chain of inter-dependencies.” As Jacobs puts it: “The system works as well as the weakest link.” Until every one of those 3,600 openings gets a plug of its own, the whole system’s at risk.

Reckoning with its crumbling present-day infrastructure while also trying to flood-proof that infrastructure against the ravages of climate change may prove difficult — when you’re in the hospital with two broken legs, you tend not to think about what might happen to you in the future.

“All these tunnel repairs take both engineering, attention, and money, and so the MTA is really pressed between a rock and a hard place,” said Jacobs.

And, of course, the long-term survival of the MTA is completely dependent on humanity taking aggressive action to bring down carbon emissions. If we don’t — and if the worst-case sea level rise estimates are borne out — much of New York City’s infrastructure will wind up underwater no matter what we do.

At the moment Jacobs and his team are engaged in testing what a storm would look like if and when all those flood-protectors are finally installed. It will be at least another year until they get any results. Ortiz is confident that the MTA has come a long way since 2012. “I think we are much better-prepared to weather a storm the likes of Sandy,” he said. But Jacobs is more sceptical. “If another Sandy were to come today, or this year, I think there would be almost the same flood conditions in subway system,” he said. “We are not yet out of the woods.”

This article was made with funding from Participant Media, the creator of “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power.”