Two hundred and fifty-two million years ago, the Earth was in a really bad place. At the boundary of the Permian and Triassic periods, our biosphere experienced its most dramatic mass extinction event (so far), one so utterly complete that it has been solemnly termed the “Great Dying”. Precious little was spared, and it’s generally been thought that it took many millions of years for life to stand back up again. But a recently-discovered fossil dating to just after the Great Dying is helping to erode our vision of a slow post-extinction recovery, showing that ecosystems recovered very quickly, were thriving, and were full of teeth. Rows upon rows of razor-edged teeth.

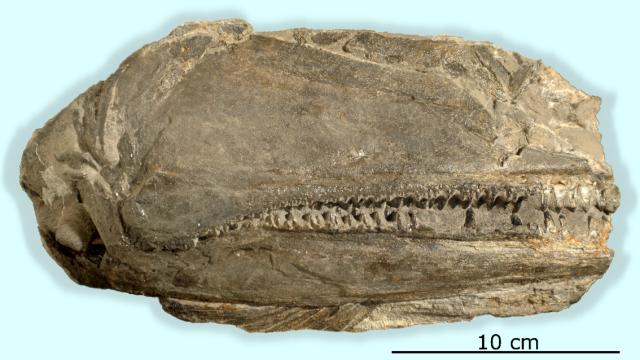

The 26cm long fossil preserving the right side of the skull of Birgeria americana. Image: University of Zurich

Meet Birgeria americana, a new species of large, predatory fish described for the first time in a recent paper in the Journal of Paleontology by a team of Swiss and US palaeontologists. The researchers discovered a partial fossil skull of the animal in northeastern Nevada — an area that, 250 million years ago, sat under an equatorial sea. Based on the size of this skull, it’s estimated that Birgeria americana was human-sized. The primitive fish had gaping jaws lined with three rows of sharp, 2.5cm-long teeth, and as if that weren’t enough, it had yet more teeth studding the centre of its hungry mouth. While other species of Birgeria were previously known to science, this new species is among the largest, and was an apex predator that likely lived and fed much like a shark; by chasing down smaller fish, tearing into them and swallowing them whole.

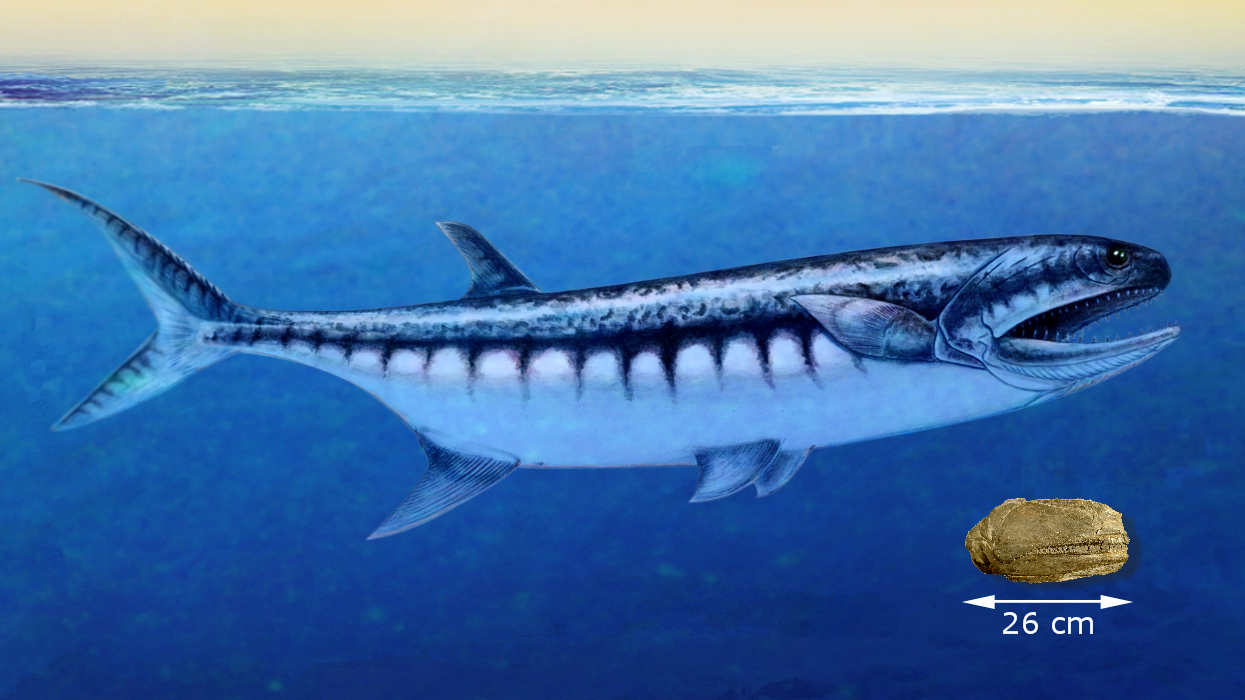

Possible look of the newly discovered predatory fish species Birgeria americana with the fossil of the skull shown at bottom right. Artwork: Nadine Bösch

But Birgeria americana‘s top predator status isn’t what makes its discovery so unexpected — it’s when this barracuda-like animal lived. The fossil dates to only one million years after the Great Dying, suggesting that despite the unmatched ecological chaos of the extinction, some ocean food webs quickly bounced back, acquiring enough depth and complexity to support big, apex predators. Far earlier than what was originally thought possible, Birgeria americana reigned over vibrant marine ecosystems with an iron fin.

This toothy, piscean predator’s discovery builds on an emerging picture of the recovery from life’s nastiest die-off, one that suggests a dogged persistence of life in the wake of cataclysm. Fossils from the early Triassic aftermath are rare, but mounting evidence from what does exist fits well alongside Birgeria americana. Bountiful ocean ecosystems, which predators like Birgeria would have depended on, existed nearby in southeastern Idaho. Land reptiles rebounded almost immediately in South Africa. Of course, the picture these few fossil relics paint is incomplete — more studies are needed to determine if life made a fast recovery everywhere, or if the places where scientists have found vibrant post-Permian ecosystems are the exception.

Still, this changing perspective on how abruptly life can get up and dust itself off may bring some relief to those worried that the ongoing, humanity-driven extinction event might permanently disrupt life itself. But, it isn’t just that “life, uh, finds a way”, the survivors find a way, and they make a new world alien to the one that came before. The question that should probably haunt humanity isn’t whether or not there will be survivors on the other side of the next mass extinction, but just how many species will get left behind.