A desert and a world that seems like our own form the backdrop of The Book of Sand, the sci-fi debut of bestselling author Mo Hayder (Birdman, The Treatment). Sadly, Hayder passed away last year, but The Book of Sand is getting a posthumous release this week — and Gizmodo has an exclusive excerpt to share.

First, here’s a summary of The Book of Sand.

Sand. A hostile world of burning sun.

Outlines of several once-busy cities shimmer on the horizon. Now empty of inhabitants, their buildings lie in ruins.

In the distance a group of people — a family — walks toward us.

Ahead lies shelter: a “shuck” the family calls home and which they know they must reach before the light fails, as to be out after dark is to invite danger and almost certain death.

To survive in this alien world of shifting sand, they must find an object hidden in or near water. But other families want it too. And they are willing to fight to the death to make it theirs.

It is beginning to rain in Fairfax County, Virginia, when McKenzie Strathie wakes up. An ordinary teenage girl living an ordinary life — except that the previous night she found a sand-lizard in her bed, and now she’s beginning to question everything around her, especially who she really is …

Two very different worlds featuring a group of extraordinary characters driven to the very limit of their endurance in a place where only the strongest will survive.

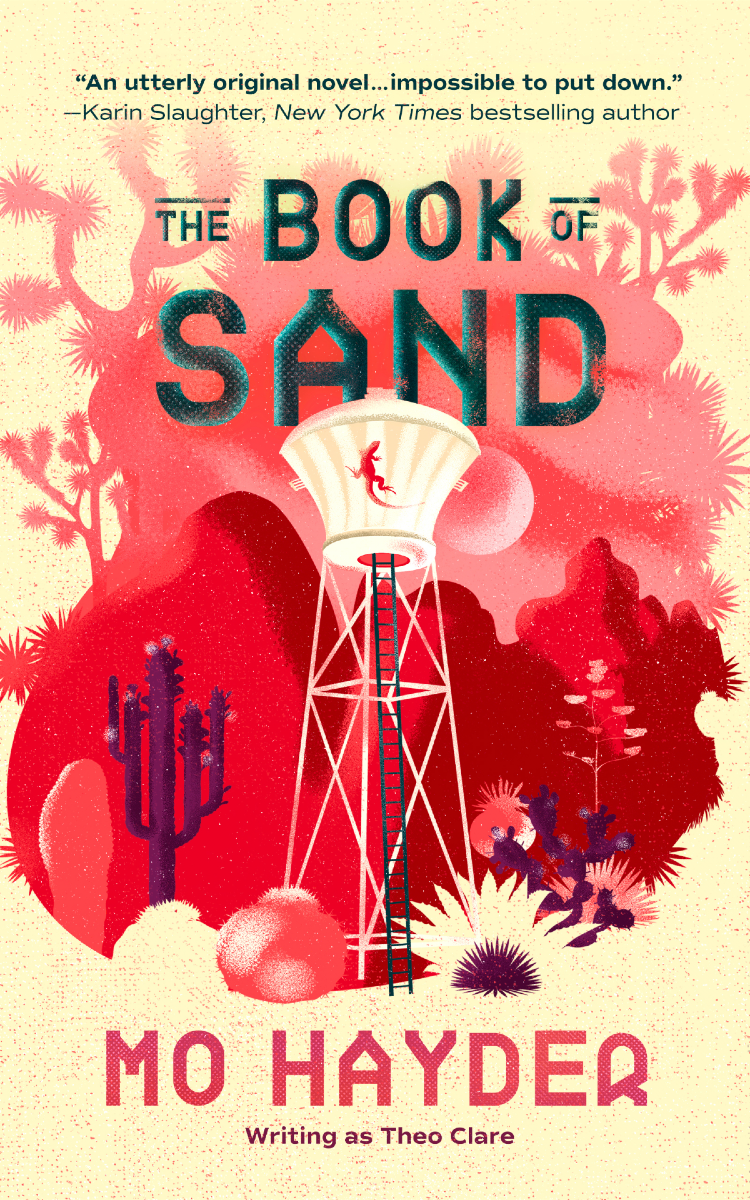

Here’s a look at the full cover, created by Sarah Riedlinger, followed by the excerpt, which introduces us to both of The Book of Sand’s worlds.

The family are eleven in total, a raggle-taggle assortment, ranging from a child of five to a huge grey man in his sixties, and though some are able-bodied, others are less so. Spider knows that of all the family he’s the strangest sight — though he stands almost two meters tall, is whiplike, and healthy as a young tree, it’s his clothes that set him apart: he wears desert boots, aviator goggles, and a tattered woman’s dress, which the slight breeze causes to flap lazily against his tanned legs. He leads the family’s single camel, laden with equipment; the camel is as downcast as the family, forlorn and battered, and she drags her feet, and her humps are pitifully slumped.

Next to Spider walks Amasha: squat and round-figured, moving like a regal ocean-going ship, her veils fluttering around her face. In her expression there is no urgency, no betrayal that she feels the same fear as the rest of the family.

Spider glances over his shoulder to check the family are keeping up. The little blond-haired girl, who has been trotting bravely next to the camel for the last two hours, is crying with fear.

“Hey,” he mutters, leaning his head sideways to Amasha. “Have you seen?”

Amasha doesn’t turn back to look — she keeps her eyes fixed on the horizon. “Of course. She’s scared. But we can’t stop.”

“She’s crying.”

“I know, I know. But for the sake of the family, we can’t stop. She has to keep up. She knows we have to get home. Don’t pay attention, she will soothe herself.”

Spider wraps the camel’s rope tighter around his fists and leans into the walk, putting everything he has into it. His eyes are itchy with tiredness, but he keeps going, placing one foot after the other, registering the places on his neck where his skin has burned in the last two days, the point in his boots where the leather is thin and rubbing his sole. He doesn’t look up at his surroundings, the long featureless tracts of sand, up to forty clicks in every direction, the distant cities and structures of iron. Vast funnel-shaped towers, some as much as a hundred meters tall and a hundred wide. Now that the sun is setting, the structures cast shadows immense as mountains collapsed across the sand.

The little girl cries louder now. Spider stops, and the camel stops obediently next to him. He ducks under the camel’s neck and bends to take the little girl in his arms, but before he can hoist her up onto his shoulders, Noor, the tall man at the head of the train, turns.

In his late twenties, he is dressed in traditional kurta pajamas of pale gold, his hair is straight and groomed, his nose high, shoulders square, and he has the natural authority of a pope. He narrows his eyes at Spider, gives his head a faint but unequivocal shake — reminding him not to disobey Amasha.

Spider lowers his arms, crouches to the little girl, who is crying hard.

“Now listen, you’ve got to keep walking — it’s almost night. You can rest soon, but for now you’ve got to keep going. You hear me?”

“I don’t wanna walk. I’m scared.”

“I know that. I know you don’t want to, and I know you’ve tried your best all day long and you’re totally flaxed, tired as a frickin’ dog, but you got to keep going. Think of it like a competition. You and Cairo or Mahmoud — who’s gonna be home first?”

The girl rubs her eyes, and her bottom lip sticks out as she swings her sullen gaze toward Cairo and Mahmoud, the little boys at the back of the line. “Extra pancakes if me first?”

“That could be arranged.”

She lets out a long sigh. Kicks the sand with her open-toed sandals. “OK. Maybe.”

And so they walk on, Spider lowering his eyes against the late sun, dragging at the camel’s halter.

It starts again when McKenzie hits junior year at high school.

She wakes one morning at three. She doesn’t need to look at her clock, she can tell the time from the position of the constellations above her skylight, so she lies on her back, blinking at them, trying to decide what woke her. There are goose bumps on her arms as if she’s midnightmare.

She takes a deep breath, from the lower ribs, because Mum says that yoga breathing is the most calming thing you can do. The room is normal, nothing out of place, the posters of the desert on the wall, the roof windows wide open, although it’s freezing. She squirms her hand down into her bed, searching for Cuddle Bunny.

She’s had Bunny since she was a kid — maybe he’s her best friend after India, the one she tells all her secrets to. She feels him warm against her belly, touches him, but there’s no fuzzy velour. No floppy stitched-up ears. Instead, a warm and scaly skin.

She gasps, and Cuddle Bunny moves, squirming hard and muscular, something scratching her belly. She pushes herself off the bed and lands in a crouch, her heart racing — hands out in front of her. The quilt is moving, undulating. She backs away from the bed, half on her hands and knees, gets to the wall, trembling, and throws the light switch.

The bedspread moves, and a head appears from under it. A lizard of some sort, but like nothing McKenzie has ever seen in her life; buff in colour, it has a dinosaur-like ruff of horns around its neck.

It blinks, then ducks back under the covers, fighting with them until it reaches the end of the bed. It drops off the bed with a thud and disappears beneath it.

She throws the door open, steps through, and slams it behind her. She stands for a moment, her heart pounding, then, taking the steps two at a time, canters down the staircase to the second floor. “Mum?” Her throat is so tight with terror the word hardly comes out.

“Mum?”

She gets to the next story down, the long passage where, dotted along the wall, at foot height, are little flower-shaped night-lights. Her brothers occupy the two bedrooms on the left — their doors are closed — and, at what seems an impossible distance, Mum and Dad’s bedroom door. Closed. She’s never seen Mum and Dad’s door closed at night; they always leave it open.

Very, very carefully, she tiptoes into the passageway, past her brothers’ doors. The bathroom on the right, the door is open, a gaping hole — a triangle of mirror just visible, cut in half by a robe hanging on the towel rack. She stands next to Mum and Dad’s door, her forehead almost touching it. She raises her hand to knock — it’s the polite thing to do — but changes her mind.

“Mum?” she whispers into the door crack. “Mum? Dad? Are you awake? Mummy? Please?”

She shivers. Her feet are bare, her vest and pajamas are thin.

Can she hear scratching on the stairs above? “Mum? Please?”

On the other side of the door, she can imagine the room, large and comforting. There are family portraits on the wall, pictures of Mum and Dad at their wedding, one of Grandpop, who was born in Shanghai and died in LA last year — that must have been a big deal. She has been back to Shanghai and seen it all: the Chinese restaurants, the hotels for the rich and famous, the long streets. There’s a sofa in the corner where Mum often has her breakfast coffee and reads The Washington Post. The curtains are blue, printed with white tulips, and Dad wears pajamas that smell like apple pie when they come warm out of the laundry. His chin is always scratchy by the end of the day.

All so safe. She pushes the door a little wider, cringing at the squeak. The room is so familiar — blue moonlight from the squares of the windows. The gentle in-and-out sounds of Mum and Dad sleeping.

“Dad?”

A sharp voice from the other side of the room. Dad’s voice. “Kenz? What’s happening?”

On the king-size bed, Mum is sitting up, rubbing her eyes sleepily. “Kenz? Honey?”

“Mum?”

“What’s up, honey?”

“I . . . I don’t know. I . . .”

“Sweetie?” Dad says sleepily. “What’s happening?”

“Mum, Dad, there’s . . . I think there’s something in my room. You’ve got to come and see.”

Sunset. Spider hates sunset. He hates the way the day seems to sag, like rotting fruit, and the familiar smell that arises, as if the ground has opened its maw. Mostly, he dislikes the fact that no one in the family will remark on it, as if talking about it or naming it could give it more power than it already has.

Noor waves his arm to muster the dawdling family. “Let’s do it,” he shouts. “We’re running out of time.”

Spider leans forward, putting extra muscle into it, dragging the exhausted camel across the sand, through the cacti that surround this area, while behind him the family ramp up their efforts. The pattering and hard breathing, the subtle spatter of sand underfoot. No one wants to be out here after dark.

Half a kilometre ahead of them, the family’s home tower rises up against the hazy desert floor. It is enormous; with a footprint bigger than that of the Eiffel Tower, it blocks out a huge quadrant of the darkening eastern sky. Its walls are riddled with rust — the sands and the salty desert winds have driven huge holes into it. An attempt has been made to paint it, to smarten it up in desert-bloom shades of violet and pale pink, but the air has flaked and cracked the paint, so now it hangs in strips as if scabs are dropping from it.

Spider’s skin is olive, though he can still burn in the relentless heat. His hair is corn blond, and his eyes are the blue of his father’s, and he struggles in this desert, always squinting, the sunlight seeming to find this special weakness in him and push its advantage. People tell him he has a fighter’s face, they say he always seems to be expecting a punch from nowhere.

Nobody speaks. At the tower Spider hitches Camel to a spike on the outer wall while he helps Noor unshackle the gate. The noise of rusting metal on metal booms around the tower, causing the family to glance anxiously over their shoulders at the empty expanses of sand around them.

Spider holds the door open and waits for every member to hurry inside. Exhausted, they nod but barely glance at him. Just as most of them are inside, the two boys at the back, Mahmoud and Cairo — always competitive, always causing trouble — dodge to the front of the line.

Tita Lily keeps her eyes on them — she half cries when she sees them moving forward. She ticks them off about their clothing and their lack of sunscreen. She worries about them not taking their hats, she worries about them showing too much skin. She is a proper worrier, Tita Lily, and cannot keep her eyes off the boys.

Cairo is trying to prove he is faster than Mahmoud — an impossibility, because the little boy, Mahmoud, is taller and stronger — but as he does so, he runs past Tita Lily. She is walking as she usually does, with her head held high, trailing her way between the cacti. She doesn’t see them until it’s too late. She trips over Cairo and is dragged by his momentum about a metre, against a cactus, before he stops, his hands out to her, a look of terror and guilt on his face.

“Tangina!” she yells into the sand. “You crazy son of bitches . . .”

Amasha comes back out of the tower, and then, when Tita Lily doesn’t jump up, the others stop and return. She is lying facedown, holding down the white Grace Kelly hat over her dark hair. Her sunglasses have come off, and there is a small stain of blood drifting up her white dress.

“A cactus,” Forlani says. He goes to her on his crutches, crouches as best he can, and tells her not to move. “Did you get dragged across a cactus?”

“Yes. Get me upstairs,” she whispers.

Elk and Hugo come back and lift Tita Lily effortlessly — she is tiny and wiry — and carry her into the tower, Forlani hobbling along next to her. There is a trail of blood, Spider sees, dark-red blood, and he doesn’t want to think of the scent it might leave.

He unhooks Camel and leads her into the tower, then turns and sets about slamming down the giant bars on the back of the gate. He is one of the strongest of the family, so this task comes to him — the other family members each have an allotted chore, and now they scatter in the dimly lit tower to perform them.

The older family members check all entrances to the tower are still secure, while the little girl, Splendour, joins the two boys, both shamefaced now, and they work as a gang, checking water supplies and turning on the power supply from the solar panels. Madeira, the farmer’s daughter, a cigar tucked behind her ear, goes to her crops, lifting the plastic coating to confirm the irrigation system hasn’t been tampered with, and reads the little thermometers. There are the animals to check on too. She dips her fingers into the water troughs and scatters grain for the chickens, four buckets of swill for the pigs.

In the middle of the disorder stands the moth-eaten camel, patient while Spider unloads their camping equipment. He hauls the bags across the sand to the lockers that are dotted around the base of the tower and throws them inside, securing each locker with a strap. He is drenched in sweat, and his mouth is sour and dry from the cured rabbit meat the family have lived on for two days.

The family’s home — the Shuck, they call it — hangs like a vast seedpod sixty meters above them, something that seems to have grown naturally like a gourd or a tumour up in the air. The access is a spindly iron ladder to its underside, where, hazy in the dwindling light, is the giant iron lock that permits entry and exit. The two carrying Tita Lily have made it to the top of the ladder and are braced there, Hugo holding her and Elk unlocking the door. Forlani is a few rungs beneath them, holding his hands across her side. His face is covered in the dark blood that weeps from her.

As Spider gets the last of the equipment stowed, he sees a slash of red high on the wall. It is the low sun throwing a single blade of light into the tower — a sign that night is upon them.

“Keep up the pace,” he yells. His voice echoes round the tower. “Eight more minutes.”

The family’s sense of urgency increases, the tasks are finished hurriedly. Splendour is crying again from fear and exhaustion, but Spider can’t go to her. He lets Amasha herd her and the remaining family members toward the centre of the tower. There are thirty meters of ladder to climb, and the children are pushed to the front to get started. Spider leads Camel to her cage as, out of the corner of his eye, he sees the children make their way up, strung like vivid beads on a necklace in the late sun. Noor and Amasha bring up the rear: Noor’s long, muscular shins are revealed under the gold pajamas, while Amasha’s jeweled hands and forehead glint. She hauls her bright pink sari up above her thighs so that it rucks around her hips. There’s no vanity here; she has to climb. Her arm muscles bulge fat and square with the effort, and sweat stains the silk.

Camel’s cloven lip is trembling and crusted black. Smears run from her eyes. She is exhausted. Spider whips up the rope and tugs at her halter. “Come on, girl.” He makes a soft click in his throat. “Come on.”

She’s a curmudgeonly character and needs to be coaxed, so he doesn’t drag at the halter but eases her along. She needs to be in the protective cage before he can trust himself to leave her. He’s made the cage with a cobbled-together arc welder; it is thirty centimeters off the floor because somehow he thinks that will protect her. He has to ease her up the ramp.

Inside the cage he takes off her halter and rubs down her hide. Her humps are flaccid, one on either side, which would be comical if it wasn’t a sign of her exhaustion. Only two days without food or water to get this bad. Her age is showing.

“Hey,” he tells her, touching her top lip. “You’ve got a guard tonight. Look at this.”

In his few free hours, he’s been working on a screen that pulls down around Camel’s sleeping cage. He will be safe in one of the Shuck pods overhead, and though the animals never suffer on the grey nights, it gnaws at him regardless that Camel has to witness what happens. He wants her protected, so he has devised a plan for a scroll-down screen. It locks first time, and when he rattles it, it stays firm.

Camel needs to drink. While she arranges herself in the cage, turning herself around to accustom herself to the new shape and dimensions, he snatches up her plastic drinking trug and makes a run for the perimeter of the tower, where the water is located. He clips open the tap and directs the head of the hose into the base of the container. It takes 180 seconds to fill, he knows this from experience, and in those moments of waiting, he takes stock of his situation. Sand caked raw on his naked legs, his lips cracked and sore. Tita Lily upstairs injured, as if they don’t have enough problems. And it’s been another two days of searching without result. Things are shit, he thinks. Truly shit.

“Spider!”

He looks up. Thirty meters overhead, the lock to the Shuck is hanging open, and in it, perched on the ladder, her legs bare, Amasha screams at him.

“Get up here.” She is holding on to the lock mechanism with one hand. With the other she beckons him, her saliva making a mist of pink in the last sunrays. “Leave her. Get up here.”

“She needs water.” He wrenches off the water clip, flips the hose out, and collects the trug handles.

“I’m telling you to leave her. She can go days without water.” He could drop the trug and run for the ladder, but he’s not going to leave Camel overnight without water, so he hefts the trug across the sand. The water tilts and laps and splashes. “Spider. Last chance!”

Patiently, he drags the container up the ramp into the cage. With the last of his strength, he hauls it up to the hooks on the side of the cage so Camel can reach it. She dips her head in, and he takes five seconds to scratch her on the top of her head, then slams the cage and makes a run for the ladder. It creaks and groans as he scampers up it. Amasha waits, her brown arm extended out of the hole. She would rather die than leave one of the family down here at nightfall.

He makes the entrance just as the last of the sunrays leave the underside of the pod. Amasha pulls him inside, slams the lock shut while he lies on his back, breathing hard.

“Don’t do that to me again. I don’t ever want to know what would happen if you were left down there. I keep thinking about Nergüi.”

“None of us want to know what would happen,” he assures her between deep breaths. “None of us.”

The room at the top of the house is as McKenzie left it — the bed covers pulled back, the pillow on the floor.

Her mother, Selena Strathie, shivers. “Honey, do you ever think about closing those windows. The bills in this place are crippling.”

McKenzie doesn’t answer. The thing about the windows — the reason she has them open, no curtains or blinds — goes back to before she can even remember and is one of the things they argue about all the time.

“Where did it go?” Dad asks. “Under the bed?”

“Uh-huh.”

Dad gets down on his hands and knees and lifts the covers, peering under the bed. “Nothing there now.”

“I did see it.”

He lifts his head and gives her a strange look. “Didn’t say you didn’t, hon.” He prowls the room, checking under her desk, opening her wardrobe, and checking carefully in there. From his top pocket, he levers out his glasses and loops the wire frames around his ears. He gets down on his knees and feels his way along the baseboards.

“Nothing.”

He goes into the shower room and hits the light. McKenzie and Mum come to stand together behind him and peer at the shower, the bathroom all gleaming in the electric light.

“It’s big,” she murmurs. “We’d see it.”

Dad opens the vanity unit and feels around under the sink, stretching to look under there.

“Nothing here.”

“Any holes it could have crawled into?”

“Nothing I can see.” After a long time of looking, Dad sits on the bathroom floor, rubbing his eyes. “I don’t know, sweetie. I just don’t know. You wanna sleep with us?”

She bites her lip. “I guess it was a nightmare. Right?” She must have been dreaming — it happens like this, she’s sure: your dreams bleed into your reality. No seams. “I’ll stay up here.”

“You want us to stay with you for a while?”

“I guess. If you’re OK with that?”

“A few minutes.”

Mum gets spare quilts and pillows out of the wardrobe, and she and Dad prop themselves against the bed, wrapping the quilts around them. McKenzie lies on her side on her bed, staring into midair. What did she just see? A lizard?

She closes her eyes and thinks about India, her friend on the other side of the development. Neither McKenzie nor India has boyfriends; frankly, no boy has ever considered them datable. India sometimes sleepwalks. She wakes up in sketchy places, like the carport or once on the borders of her yard, looking down into the creek that runs way below the cliffside behind the houses. India’s mum said that was the scariest.

Is that what happened to McKenzie? Has she just sleepwalked into her parents’ room? Dreamed up a lizard?

“Is she asleep?” Mum murmurs to Dad, and although it’s the most natural thing to open her eyes and say, “Not yet, but don’t stay,” McKenzie keeps her eyes closed. She thinks her parents worry about her in a way they don’t worry about her brothers, and she wishes she knew why.

There is a long silence. She can feel her parents’ gaze on her face, but keeps breathing in and out, in and out.

“She’s gone.” Dad yawns, gets to his feet.

Mum, after a while, gets to her feet and seems to spend a bit of time pushing the quilt back into the wardrobe. She’s a card-carrying neat freak.

It’s only when they get to the door that Mum speaks. “Scott,” she murmurs, real sad and low, “you don’t think it’s happening again, do you?”

From The Book of Sand by Mo Hayder, writing as Theo Clare. Used with the permission of the publisher, Blackstone Publishing. Copyright ©2022 by Mo Hayder.

The Book of Sand by Mo Hayder, writing as Theo Clare, will be released July 19. You can pre-order it here.

Want more Gizmodo news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel and Star Wars releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about House of the Dragon and Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.