Experts from some of the nation’s leading civil and digital rights organisations say a report published by Meta last week, presented as an exhaustive review of its impact on human rights, in reality offers “zero” information about its actual impact on the world. The first Meta Human Rights Report should be viewed instead, the experts said, as merely the latest in a long line of efforts by the company to whitewash a history of fomenting hatred, violence, and extremism across the globe, the product of an unrelenting quest for greater engagement and profit.

“Let’s be perfectly clear: This is just a lengthy PR product with the words ‘Human Rights Report’ printed on the side,” said Jesse Lehrich, co-founder of Accountable Tech, a nonprofit focused on countering disinformation.

Released July 14, the 83-page document offers a window into Meta’s philosophy toward human rights on its platforms as authored by its director of human rights, Miranda Sissons, and product policy manager for human rights Iain Levine, a former longtime leader at Human Rights Watch. The report aims to take stock of potential human rights concerns surrounding the company’s policies, products, and business model as well as to respond to critics who’ve repeatedly pilloried Meta for encouraging hate and harm.

Meta’s report breaks down its approach to thorny issues like government takedown requests and end-to-end encryption and summarises what the company views as its impact on civil rights in multiple countries. But rights groups analysing the document say it’s not a reckoning with real-world ills caused by Facebook, Instagram, and Meta’s other products. Instead, experts described the work as largely one of self-plagiarism, recycling past PR statements while citing them as evidence of progress on an array of important issues. A section about “Election Integrity,” for instance, which boasts of Meta’s efforts to “better protect elections” and “empower people to vote,” contains links to seven external documents — all of them produced by Meta itself. The report fails to mention, however, that many of the safeguards it touts are no longer in place.

“The entire document is corporate propaganda masquerading as honest self-reflection,” added Lehrich, saying the company’s playbook for responding to criticism has not changed since its inception. “The question is not whether Mark Zuckerberg will have a sudden moral awakening one of these days, but when policymakers will subject tech giants to actual accountability.”

Facebook did not respond to a request for comment on experts’ evaluations of its report.

Meta has historically struggled to maintain face in the United States while operating in numerous countries found frequently to violate human rights, as have many of its competitors like Google and Twitter. Company whistleblower Frances Haugen alleged under oath last fall that Meta had been “literally fanning ethnic violence” in countries like Ethiopia. Last week’s report seeks — and fails — to address the contradiction, rights groups told Gizmodo.

“Facebook’s Human Rights Assessment Report is 83 pages promoting itself and restating promises that the company has already made, but failed to follow through on. There are zero pages in the report of actual human rights impact information, acknowledgment or remorse for its role in atrocities across the globe, or how it plans to fully enact policies, including in non-English languages,” said Wendy Via, co-founder and president of Global Project Against Hate and Extremism.

Meta repeatedly points to its renewed emphasis on encryption and attempts to limit unnecessary government takedown requests as key examples illustrating its commitment to human rights. It claims to only respond to requests for user information that are “consistent with internationally recognised standards on human rights” and says it’s willing to push back against overly broad requests that violate internal policies or local laws. Yet some experts said Meta’s approach fails to fully grapple with the root problems driving government data requests.

Meta’s hunger for increasingly more intimate levels of personal data — the fuel for what is virtually its only source of revenue, advertising — is what invariably attracts governments interested in abusing access to its records, said Isedua Oribhabor, business and human rights lead at the nonprofit Access Now. “The more products and services the company has and the more ways they have of collecting data, that’s just more fodder for governments to continue to try and access that,” she said.

Meta could demonstrate its commitment to users’ privacy more clearly, Oribhabor added, by collecting only the minimal amount of data needed to make the services it provides function.

Some experts said they’d grown frustrated with Meta’s increasingly lengthy list of transparency reports, describing those documents as initially appearing useful but ultimately devoid of impact and self-scrutiny. Whether reporting on widely viewed content or government requests for user data, Meta’s efforts at accountability are belied by a clear motivation to present the rosiest image of the company possible, rights groups said.

In 2018, the United Nations’ top human rights commissioner said the company’s response to evidence it was fuelling state genocide against the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar had been “slow and ineffective.” The following year, U.N. Investigator Christopher Sidoti told Gizmodo that while Meta had made some “meaningful” changes, the company’s response to the findings remained “not nearly sufficient.” The U.N. did not offer comment on the Meta Human Rights Report published last week.

Around a dozen pages of the report are dedicated to assessing Meta’s impact in countries such Myanmar, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, and India — areas all rife with significant political unrest in recent years. Meta claims its assessments provide a “detailed, direct form of human rights due diligence,” allowing it and other companies to “to identify potential human rights risks and impacts” and “promote human rights” while seeking to “prevent and mitigate risks.”

Ostensibly, Meta expected these summaries to serve as an example of transparent disclosure, but experts don’t see it that way. Multiple rights groups described the sections as brief, biased interpretations of past reports that failed to accurately capture Meta’s destabilizing role in these regions. Rather than dig deep into the “salient human rights risks” of the named countries, the document appears aimed at leaving readers with the impression that past issues have already been adequately addressed, Oribhador said.

Meta fails, Oribhabor elaborated, “to take the extra step needed to make the link that because it is the main platform for communication, it is also the main platform for spreading hate and incitement to violence.”

Even before the report, Meta was facing renewed criticism from civil and digital rights groups from across the world, particularly those in Eastern Europe, India, and Kenya. A far more detailed report on its impact, authored by the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism (GPAHE) last year, accused Meta of having a “horrifically damaging effect on democracies, societies and vulnerable populations around the world,” saying bigoted populist leaders and far-right political parties had harnessed its technology to achieve “political heights likely previously unattainable.” In contrast to Meta, GPAHE relied heavily on multiple independent regional sources to reach its conclusions. One such non-governmental organisation based in Belgrade, the SHARE Foundation, asserted that companies like Meta have “simply no incentive” to invest in content moderation in areas with “relatively small language groups” like Serbia.

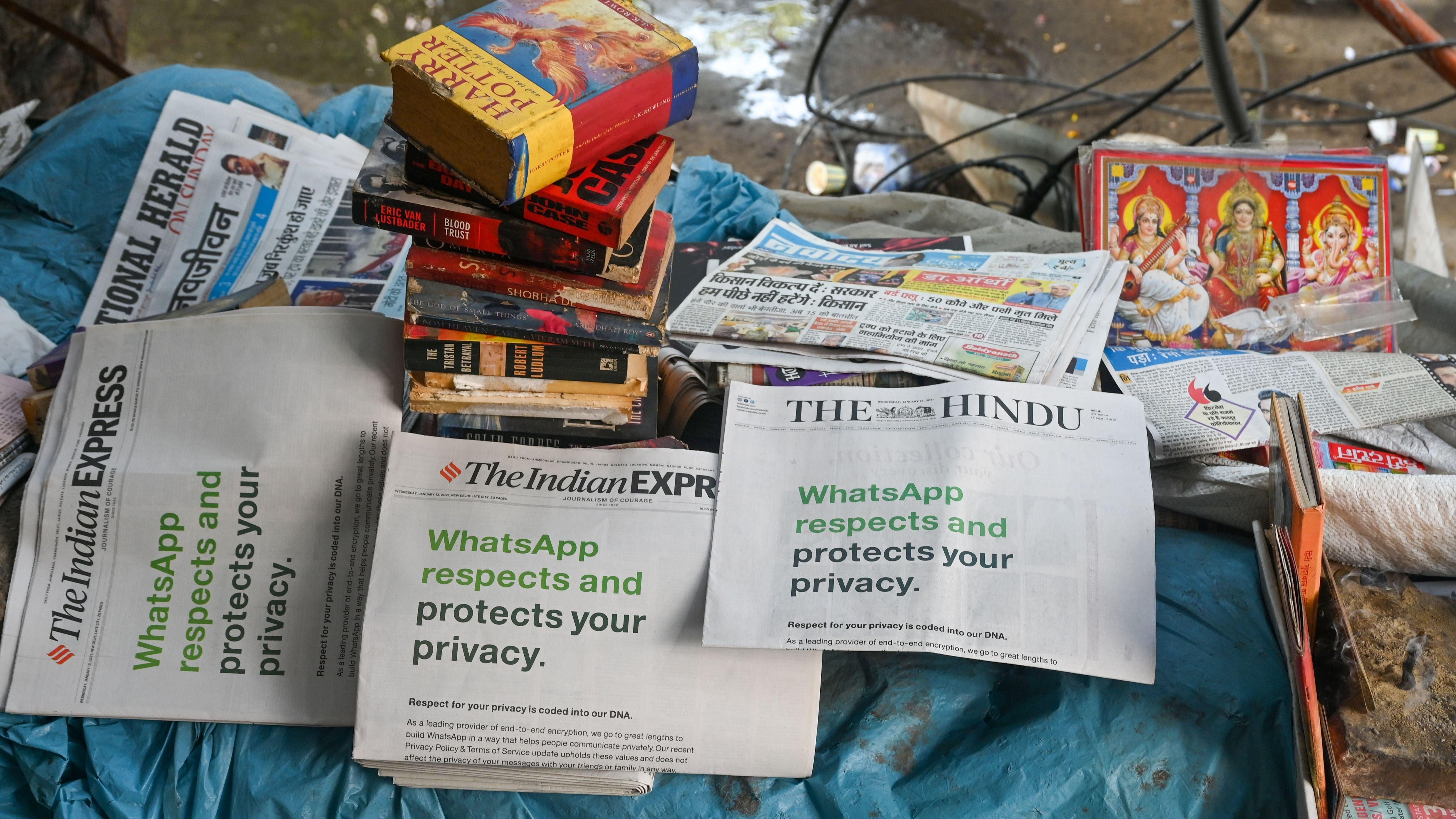

The GPAHE report further highlighted Facebook’s role in the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, whose party has fuelled religious bigotry in the country and ignored violence against India’s minority Muslim population.

Human rights issues in India represent the biggest controversy surrounding Meta’s analysis of its own impact. The Real Facebook Oversight Board, a watchdog organisation made up of global experts working to hold Meta accountable, accused the company of “whitewashing the religious violence fomented in India across their platforms,” saying that while Meta had promised to consult with civil society groups before releasing last week’s report, many had “no notice of this report or any input at all.”

An independent assessment of Meta’s role in India does exist, one commissioned by the company itself. However, no one outside Meta has yet seen it. Experts have heavily criticised Meta’s failure to disclose a long-delayed evaluation of its role in spreading hate speech and inciting violence in the country. Facebook contracted Foley Hoag, an outside law firm, to carry out the assessment in 2020. The law firm reportedly interviewed some 40 civil society stakeholders, activists, and journalists. The firm’s report has neither been published nor even given a release date. Rights groups have repeatedly accused Facebook of attempting to stifle the report and narrow the scope of its findings. Even those involved in the assessment have soured on it. Ritumbra Manuvie, one of the civil society members interviewed by Foley Hoag, told Time last week that Meta’s summary of its work on India amounted to a “cover-up.”

Meta paraphrases the Hoag report in a handful of sentences in last week’s human rights report, leading with a claim that it “provided an invaluable space for civil society to organise and gain momentum,” and “users with essential information and facts on voting.” It claims the report found its platforms have the “potential” to be used by “third parties” to perpetuate “hatred that incites hostility, discrimination, or violence,” but added in its own report should not be “construed as admission, agreement with, or acceptance,” of any findings. Meta has not committed to releasing the full Hoag report.

“Despite growing pressure to publish the assessment — and the release of troves of internal documents detailing the toll of their breathtaking negligence — Facebook expects us to believe that the unreleased assessment primarily lauds the ‘invaluable space for civil society’ they have created,” Accountable Tech’s Lehrich said.

He sighed, adding, “Give me a fucking break.”

The report’s myopia likewise extends to Africa, critics said. “Beyond India, the report is a work of fiction, denial and willful ignorance,” the Real Facebook Oversight Board said, accusing Meta specifically of “ignoring the unconscionable legal action against Daniel Moutang, the whistleblower in Kenya who has alleged significant human rights abuses in the company’s outsourced content moderation centres.”

Moutang, a Meta content moderator from South Africa contracted through a third-party company, said in an op-ed this spring that he and his colleagues had been constantly bombarded with images of torture and sexual exploitation of children. Attempts to unionize his workplace to fight for better conditions were met with “intimidation, bullying, and coercion,” he said. “I believe organising led to retaliation for me and my colleagues,” Moutang wrote. “On August 20, 2019, I was fired, lost my visa, and had to leave Kenya.”

Meta is foregrounding its work on human rights as it stakes its business on the development of future technologies like its titular “metaverse,” a theoretical virtual space aiming to blend the real world with the digital through the use of virtual and augmented realities. How it approaches human rights in two-dimensional digital spaces may well forecast how it governs three-dimensional ones.

“Most glaring is Facebook’s assertion that its policies are carefully created to ‘value each voice equally’ and protect those of marginalised communities when there are stacks of examples of how they routinely fail in this regard, instead making the choice to lift the voices of the politically powerful and influential people to further its economic interests,” the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism’s Via said.

Meta’s huge impact may be impossible to summarize in a single report, even one authored by the company itself. Nora Benavides, director of digital justice and civil rights at the nonprofit Free Press, said that the report shows a global company conscious of the extent to which its policies and practices impact life around the world.

“How could a company of Meta’s size ever adequately speak to what it’s doing in 83 pages? That alone suggests a shirking of its seriousness or responsibility,” she said.

But awareness isn’t enough, and the report falls short, according to Benavides.

“What they didn’t report on had egregious effects on human rights for every single category in this report. Close your eyes and pick from the table of contents,” she added. “The fact that every single aspect of human discourse is covered in its human rights report and it’s only 83 pages means they must not be doing a very good job being accountable for human rights.”