Did a hacktivist group hack the Belarusian railway system or not? Confirmation of the alleged breach remains elusive, though the allegations continue to intrigue security experts and commentators.

On Monday, reports broke that a “pro-democracy” hacktivist group calling themselves Belarusian Cyber Partisans (BCP) were responsible for a ransomware attack on the country’s rail system. Reputed to be a disaffected band of former Belarusian security personnel, the Partisans claimed they had encrypted some of the railway’s “servers, databases and workstations,” in an attempt to disable the country’s train network.

Why? The hacktivists accuse the Belarusian government of corruption and claim its dictator, Alexander Lukashenko, is using the railway to aid Russia in its ongoing military threats toward Ukraine.

“The goal was to disrupt the work of freight trains in the hope it will affect indirectly Russian troops using the railroad to carry weapons and equipment to the Ukrainian border,” said Yuliana Shemetovitz, the group’s spokesperson, in an email to Gizmodo.

“CPs [Cyber Partisans] don’t want Russian soldiers in Belarus since it compromises the sovereignty of the country and puts it in danger of occupation,” Shemetovitz continued. “It also pulls Belarus into a war with Ukraine. And probably Belarusian soldiers would have to participate in it and die for this meaningless war.”

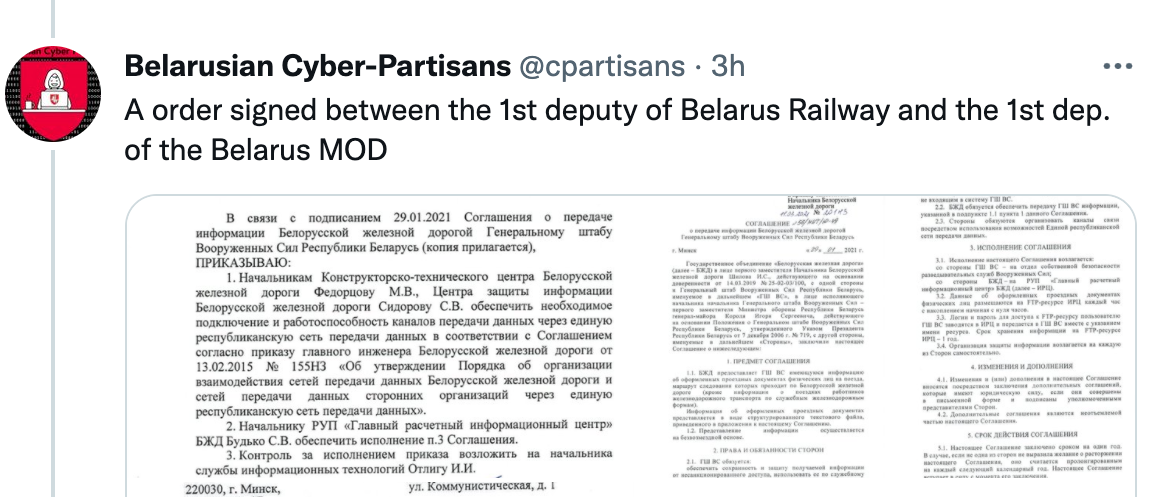

On Tuesday, the hacktivist group also continued to publish images to Twitter that are alleged to be documents compromised in the attack. “We were challenged by the media to provide more proofs for hacking the Belarus Railway,” the group tweeted, sharing images of what looked like IT-related memos and technical requests filed from inside the state-owned company.

According to Shemetovitz, the BCP first hacked the railway system back in December and lingered in its network for several weeks, in order “to prepare for a stronger attack,” which they claim to have performed on Jan. 23. The attack, which used ransomware, lasted about ten hours — from 11 pm until about 9 am the next morning, she said.

Shemetovitz admitted that the attack didn’t totally work. “We know that the electronic tickets are still affected, the trains were delayed and the attack disrupted the schedule. The main goal is not achieved yet but we can assess the results a little later, as it hasn’t been enough time to see how the regime will react,” he said.

The attack is said to be part of a broader hacking campaign targeted at the Belarusian government that the BCP calls “Scorching Heat.” The campaign began in November, when the hackers attacked the Academy of Public Administration of Belarus, allegedly encrypting the agency’s entire network. According to Shemetovitz, the hackers have also attacked Belaruskali, one of the largest state-owned companies in the country, as well as Mogilevtransmash, a major car company in Belarus.

Franak Viačorka, a local journalist who was one of the first people to broadcast news of the apparent railway incident via social media, claimed on Tuesday that Belarusian security services had recently “searched the [railway] company office for suspects in the attack,” adding to the narrative that the attack had successfully spurred a response by the government.

If all of this is true, the railway attack represents one of the most dramatic examples of hacktivist intervention in living memory. The Partisans do have a track record of hacking Belarusian government agencies — which puts it firmly in the realm of the possible. As Wired’s Andy Greenberg notes, the attack could represent a first for hacktivism — a bold, new merging of activism and cybercrime, the likes of which we’ve probably never seen before. Rarely — if ever — have hacktivists used such destructive means to achieve their ends.

The only problem is that there’s no independent confirmation yet that it actually happened. To be honest, we might not get one, either. Neither the Belarusian government nor the railway itself has published information on the incident, and independent media reports remain scarce. A notification to train passengers about electronic difficulties on Jan. 24 — the alleged day of the hack — remains the only potential evidence that the story is true, beyond what the hacktivists themselves have shared.

When a security firm, Curated Intelligence, recently reached out to the BCP and asked them for a sample of the malware used in the attack, the group turned them down. A malware sample could have been forensically analysed to provide further proof of the attack. Instead, the hacktivists sent them a copy of what is purported to be an internal Belarusian incident report from one of the BCP’s prior attacks on a government agency. Security researchers found the documents to be “unclear,” though commented it might ultimately be helpful in understanding the hacker group’s tactics. The BCP ultimately told the firm that they would “gladly” share a malware sample “once the authoritarian regime in Belarus is gone.”