Up until Resurrections, the Matrix series hasn’t directly acknowledged LGBTQ people at all. Switch was written as trans in the original Matrix screenplay but the character was changed for the finished film, because studio executives were confused. That didn’t stop queer readings of the work, of course, which intensified after directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski came out as trans women.

Even Lilly Wachowski encouraged these readings in the 2020 documentary Disclosure: “The Matrix was all about the desire for transformation, but it was all coming from a closeted point of view.” The Matrix Resurrections is the first film in the series made since the Wachowskis both came out. Queer and trans issues are not interchangable, but the latest sequel offered an opportunity to acknowledge those readings. Lana Wachowski (directing without Lilly, who has gravitated away from science fiction in favour of more realistic queer stories) and the crew took it.

In the latest instalment of the saga, Neo is alive (surprise) and trapped in a new Matrix, living as video game developer Thomas Anderson. While working on an ambitious new project titled Binary (very subtle…), his boss Smith strong-arms him into developing a sequel to his blockbuster video game series The Matrix, which is similar to the movie trilogy we’ve all seen and that Neo can’t remember he actually lived through.

This meta first act allows for Resurrections to directly comment on the allegorical interpretations of The Matrix. In a meeting where Anderson’s development team discusses what The Matrix games were about, one developer chimes in that the original story was about “trans politics,” the first direct LGBTQ reference in the series. This exchange is tongue-in-cheek, but it’s not a complete rejection of this reading either. The series does obviously contain many of the things these developers bring up — “bullet-time!” “WTF!” — and the scene is just lightly ridiculing those who say The Matrix is about any one thing.

Most of the queer content in Resurrections follows the same allegorical lines as the original, repeating old scenarios of the awakened Neo and Trinity rejecting their “deadnames” and adding in copious new references to “binaries” which have inevitably been read as a commentary on gender binaries. While there still aren’t any characters directly stated to be queer, Resurrections makes LGBTQ headcanons a lot easier than the previous films did, giving Niobe and Freya as well as Bugs and Lexi enough onscreen displays of affection to read them as couples.

What might be the most fascinating aspect of The Matrix Resurrections’ queer subtext, however, is in regards to its villains. Queer-coded villains have a long and problematic history in Hollywood, but in spite of or even because of this history, they’re often a source of fascination for queer artists and audiences. So when Lana Wachowski decided to cast two openly gay actors, Jonathan Groff and Neil Patrick Harris, in the roles of Resurrections’ two primary antagonists, Agent Smith and the Analyst, I’m pretty sure she knew exactly what she was doing.

Agent Smith is the richer character in regards to queer subtext, since some degree of subtext was already part of Hugo Weaving’s interpretation of his character in the original trilogy. In queer readings of The Matrix, Smith has been compared to homophobic closeted preachers, trans women who force themselves to live as men, and “conversion therapy” advocates. When Smith tells Morpheus in the first film, “I hate this place, this zoo, this prison, this reality, whatever you want to call it,” his self-loathing comes through loud and clear.

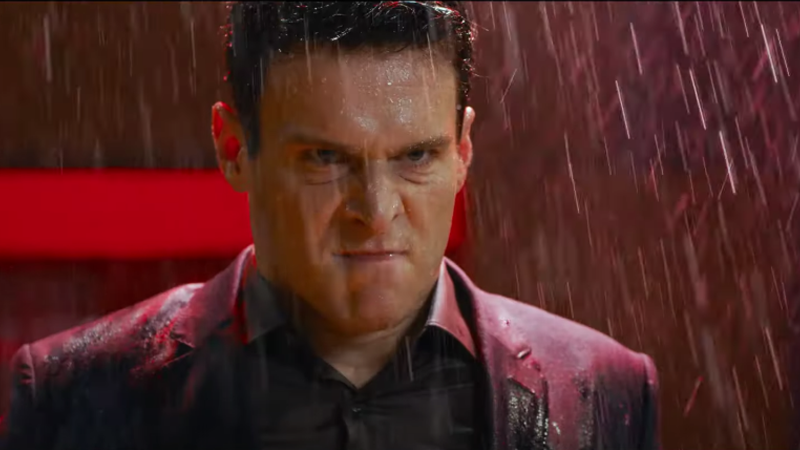

If Weaving’s Smith is closeted, then Groff’s Smith has basically come out. Not as trans (Lana already made it clear that The Matrix isn’t one-to-one allegory for transness), but as gay. The queer-coding on the rebooted Smith is so heavy that it almost goes beyond coding; it’s as obvious as it could be without becoming either an offensive stereotype or explicit enough to warrant the sort of censorship common with LGBTQ+ material in blockbuster movies around the world. Though Groff hasn’t spoken on playing Smith as gay, he has described the film as a whole as being “more queer,” and it’s easy to read this bleeding into his performance.

In attitude alone, it’s evident that Groff’s Smith is more relaxed and comfortable in his own skin than Weaving’s Smith was. When Smith makes his appeal to Neo around an hour and 22 minutes into Resurrections, it becomes clear he’s also a lot more comfortable expressing affection for his legendary opponent. “There’s so many theories about the two of them,” Berg, the crew’s resident Neo scholar, coyly quips, perhaps alluding to Smith/Neo shippers. Smith tells Neo, “You never appreciated our relationship,” and says that the Analyst used their “bond” and made it a “chain.” Smith asks Neo his opinion on his “piercing blue eyes,” and takes a lot of pauses to make flirty faces. It’s total shipper-bait.

When they’re finally about to fight, Smith says that “Anderson and Smith” are one of the “binaries that form the nature of things.” Given the gender subtext of Resurrections’ criticism of binaries, feel free to make a “the two genders” joke here. With how heavy BDSM imagery is throughout the Matrix series, it’s also not hard to see some sadomasochistic eroticism in Smith’s passionate desire to fight both Neo and the Analyst, the latter of whom he suggestively claims had “his leash on my neck.” Later in the movie, when Smith ultimately saves Neo and Trinity from the Analyst, he says that when Neo got out of the Matrix and awakened him, “I was free to be me.” (Also, Smith and Morpheus technically have a kid together in the form of Yahya Abdul-Mateen II’s new Morpheus program character.)

Aside from Smith’s sadomasochistic comments and the casting of Harris, the Analyst isn’t as heavily queer-coded as Smith. He’s coded more as one of those “alt right” Matrix fans who’ve appropriated the original’s imagery than anything, monologuing about “alternative facts” and looking down on others as “sheeple.” While most viewers know that Harris is a gay man, they also know that his most iconic characters, from Barney Stinson to his own caricature in the Harold & Kumar movies, have been extremely heterosexual.

Yet even when playing a character so wildly different from himself on the page, Harris says that he played the character as a “version of myself.” Given the Analyst’s tricky relationship with the truth and the hyper-stylised nature of the original Matrix trilogy, it was easy for him to lean into similar stylization, but Lana Wachowski’s style has evolved in a more naturalistic direction, leaving Harris somewhat confused over how “truthful” his performance needed to be. The Analyst obviously isn’t the “true” Neil Patrick Harris, but nonetheless anyone who knows the actor is going to bring their knowledge of his public identity to the Analyst. In combination with the heavy queer-coding of Smith, it creates a strange phenomenon in which the two most significant agents of a system often read as a metaphor for conformity and anti-LGBTQ oppression give off at least some gay vibes.

In 1999, being openly queer automatically made one an enemy of the system. In 2021, this isn’t necessarily the case. Rights such as marriage and protection from employment discrimination have at least been written into law, and enough has changed that some (mostly cis, mostly white, mostly male) queer people are able to hold power within the system. Just because our governments and corporations are more gay-friendly than before, however, doesn’t necessarily make them more friendly in general. “Rainbow capitalism” is often performative at best towards the needs of the LGBTQ community, and “pinkwashing” uses nominal progressiveness on queer issues to distract from harmful actions in other areas.

One of the main themes of The Matrix Resurrections is that systems of power appropriate and assimilate forces that were originally in defiance of said systems. This is most obvious in how Neo’s story of rebellion against the Matrix has been turned into a video game franchise within the Matrix itself. Subversion is reduced to a corporate product that most audiences don’t even understand the intended message of. As Bugs says, “They took your story, something that meant so much to people like me, and turned it into something trivial.” When the Analyst uses bullet time, The Matrix’s most iconic image, as a weapon to freeze Neo and Trinity in place, it’s perfectly symbolic of how the aesthetics of revolution get warped against their original meaning.

The queer-coded villains of Resurrections are yet another example of this assimilation into the system, while providing two very different responses to it. The Analyst embraces his power within this system, whereas Smith is ultimately able to redeem himself by breaking away from it. There have always been heated debates over whether the goals of the LGBTQ movement should be focused on showing the cishet world that queer people can be “just like everyone else” or whether it’s better to reject normality and respectability politics. Lana Wachowski might object to anyone saying what The Matrix Resurrections is “about,” but it’s fair to say at least part of it is an anti-assimilationist message: not gay as in happy, but queer as in fuck you.