To be alive in 2022 is to know we could shuffle off this mortal coil at any given moment. To paraphrase the prophet Phoebe Bridgers: All the billboards say the end is near.

One particular billboard counting down our perpetual demise is the inescapable Doomsday Clock, a 75-year-old relic that exists to tell us we’re all about to die. On Thursday, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced that the Doomsday Clock in 2022 has been set at 100 seconds to midnight — the same time as last year. And the year before. What does this mean, exactly? According to the Bulletin, the “continuing and dangerous threats posed by nuclear weapons, climate change, disruptive technologies, and covid-19” have brought us perilously close to extinguishing humanity. Again. Still.

“All of these factors were exacerbated by ‘a corrupted information ecosphere that undermines rational decision making,’” the Bulletin said in its announcement of the new (same) time.

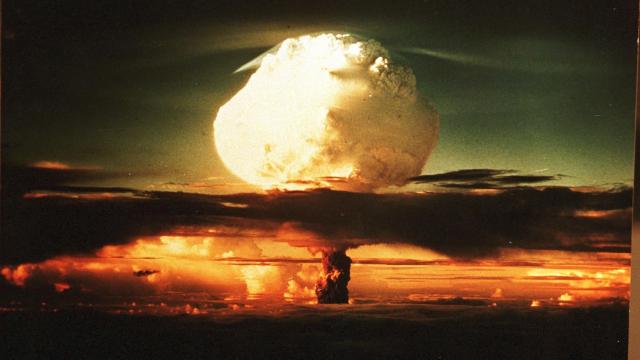

The Doomsday Clock was created in 1947 by some of the Manhattan Project scientists who worked on the atomic bomb. Those scientists expected nuclear weapons to be the cause of our collective annihilation, which seemed, uh, likely, if not a foregone conclusion as the Cold War set in. The clock was originally set at 7 minutes to midnight, which probably seemed terrifying at the time. Over the years, we’ve seen the time bounce back and forth, but the furthest we’ve ever been from doom is 17 minutes to midnight back in 1991. It was a simpler time, when the U.S. and Russia both agreed to chill out with nuclear weapons. But midnight has always been looming. We get it. We’re doomed.

The sense of dread has also never been easier to feel. Open Twitter for the morning doomscroll or just click the homepage of this very site, and you’ll receive no shortage of reminders. The very “corrupted information ecosphere” the clockmakers warned about is blasting out a doom warning siren every day that makes the clock seem anachronistic and quaint.

The Doomsday Clock is “a symbol of danger, of hope, of caution, and of our responsibility to one another,” according to the product listing of a Doomsday Clock coffee table book commemorating its 75th anniversary.

Symbolically, yes, the clock has clearly been influential. It’s a pop culture touchstone that has been referenced in some of the greatest art ever made (see: Dr. Strangelove, The Simpsons). But it’s also kind of a joke. In 75 years of glancing at the clock, midnight has always been just moments away. Human beings, when faced with certain death, have a tendency to become nihilistic rather than rational. If doom is imminent, why not have fun while watching the world burn to the ground? The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists does outline a series of action items that could help society turn back the clock, so to speak, but this is where the entire clock concept falls apart.

The Doomsday Clock’s biggest failure is when it comes to climate change, which wasn’t factored into the Bulletin’s doom calculations until 2007. The clock’s initial preoccupation with nuclear war makes sense if you squint right. Midnight hits when the bombs fall.

But there’s no bomb coming with climate change. Instead, it’s a slow violence that began at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution and continues to this day. Every second we continue to burn fossil fuels pushes the climate further outside the boundaries that humans have known and thrived in. Even if emissions magically stopped tomorrow, the repercussions of these tiny atmospheric explosions would ricochet into the future.

Carbon dioxide can spend 100 years in the atmosphere. That means the impacts we’re living through today date back to well before the Doomsday Clock even existed. Using it as a means to track the climate crisis is woefully inadequate on that front alone.

The problem, though, runs even deeper. The impacts of climate change are not linear. Instead, they’re accelerating. You need only look at the past few years to see that: California went from a challenging fire regime to angry red skies every summer in a remarkably short period of time. Heat waves have become dramatically more common, hitting every corner of the globe in deadly fashion. The reason the Doomsday Clock can never capture this is that we’re now so close to midnight by its accounting that there’s no hope it will ever portray the acceleration to come.

But then there will never actually be a midnight for the climate crisis. Midnight arrives at different times for every person on Earth. Futurist Alex Steffen has said that the present is “transapocalyptic,” a phrase that perfectly encapsulates this form of existence.

“We live, today, in a world where some people worry about their family surviving the trip to the next source of water, and others fret over having to buy their second-favourite brand of coffee,” he wrote. “A transapocalypse is a spectrum.”

In that spectrum, there is no midnight. The bell will never toll for the planet. Instead, it’s just shades of night that we all live through at various points. Even when society halts our carbon-fuelled nightmare by ending the use of fossil fuels, the return to daylight won’t be linear or evenly distributed. Instead, it will be more like watching the sun rise from space, the bleeding edge of dawn crawling across the planet to paint the landscape yellow and the oceans blue. Patches of clouds will mean the light is more diffuse in some places. Parts of the world may even remain in the dark like the inky black that grips the Arctic each winter.

The end will always be near, at least for now. No clock could ever capture that feeling.