A team of researchers at Johns Hopkins University and elsewhere say their robot was able to pull off a complicated and delicate surgical procedure on a pig without the assistance of humans for the first time. What’s more, the robot even appeared to do the job better than human surgeons.

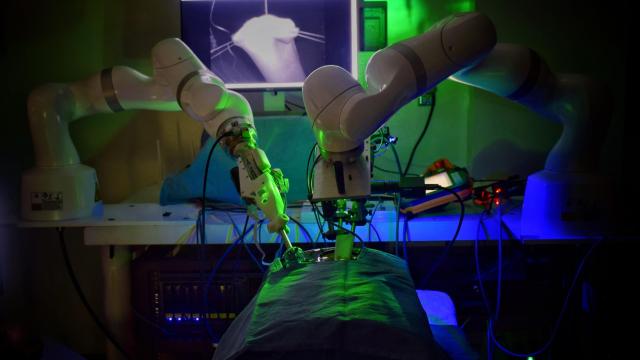

The use of robots in the operating room isn’t new, but current technologies in wide use, like the Da Vinci system, are still controlled by a human surgeon. The Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot, or STAR, system being developed by Axel Krieger and his colleagues is different.

“In contrast, STAR is the first robotic system to plan, adapt, and execute a surgical plan in soft tissue without human intervention,” Krieger, an assistant professor in mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins, told Gizmodo in an email.

Over the years, Krieger and his team have demonstrated that STAR can perform important surgical tasks as well as or even better than human surgeons, though still with some human input involved. In their latest research, published Wednesday in Science Robotics, they present data showing that STAR can autonomously perform a complex soft tissue surgery in pigs laparoscopically, mean done with only small incisions.

The procedure is known as small intestine anastomosis, and it requires reconnecting the ends of an intestine (this might be needed if part of the intestine were removed to treat a tumour, for instance). It’s a surgery that requires finesse and precision, since even a tiny mistake can leave behind leaks. Working with soft tissue, as opposed to rigid structures like bones, is a challenge for any surgeon, since they may have to adjust on the fly if it moves around in the body.

But in these tests, which involved STAR operating on four pigs, the robot seemed to pass with flying colours. Compared to data obtained from human-performed operations, the team reported, STAR’s suturing and stitches were deemed to be more accurate and consistent. There were also no leaks detected in the operated-on pigs.

Automating STAR to pull off this kind of complex task required several innovations, Krieger said. Standard surgical tools needed to be modified to be used by STAR, for one. The robot was also outfitted with a combination of near infrared and structure light cameras in order to reconstruct a three-dimensional image of the surgical site, and it required programming to create a surgical plan that could be adjusted as needed to account for things like tissue obstructions. But the results indicate that building an autonomous surgical robot is more than possible and “not just a figment of one’s imagination,” Krieger said.

For the foreseeable future, though, STAR and similar robots will continue to play assistant to human surgeons, rather than take over completely. But even this could be an important step forward for making surgeries safer, by allowing surgeons to better standardize tricky operations like an anastomosis, a task that’s performed over a million times in the U.S. annually, according to Krieger. Krieger and his team also hope that systems like STAR can revolutionise other difficult soft tissue procedures such as tumour resections. And they envision a future where “autonomous robotic surgery systems could help treat patients outside of a normal hospital settings, for example, in trauma situations on the way to the hospital.”

In the meantime, the team plans to upgrade STAR and its capabilities even further. In the current experiments, for instance, the robot still required the manual placement of markers along the pig’s tissues to aid its tracking. They’ve now started to work on a markerless approach that should be able to make the robot’s cameras less bulky and surgical planning simpler.