Lawyers for the American Civil Liberties Union are fighting to uncover more about the FBI’s role in helping local police acquire powerful mobile phone surveillance devices known widely as “stingrays.” The true scope of their use against Americans has, by design, remained a closely guarded secret for more than a decade. This is thanks to secrecy requirements devised by the federal government, which police departments and prosecutors have followed to an extreme.

In a lawsuit filed this week in Manhattan federal court, the ACLU accuses the FBI of violating the nation’s freedom of information law by refusing to even acknowledge the existence of any documents that contractually prohibit police from disclosing information about stingrays. Should there be any doubt, these documents do, in fact, exist. I should know. I’m staring at several of them right now.

We human beings must find, Bertrand Russell once wrote, “in our own purely private experiences, characteristics which show, or tend to show, that there are in the world things other than ourselves and our private experiences.” (Characteristically, these documents are still warm from my printer.) From Democritus, first to posit the existence of atoms, to Descartes, who believed in a malice-free God who would never deceive him into believing in that which consists of nothing, the question of what, if anything, exists beyond ourselves has been keeping philosophers up at night for more than two millennia.

That is over now. These documents are definitely real. I am touching them. With my hand.

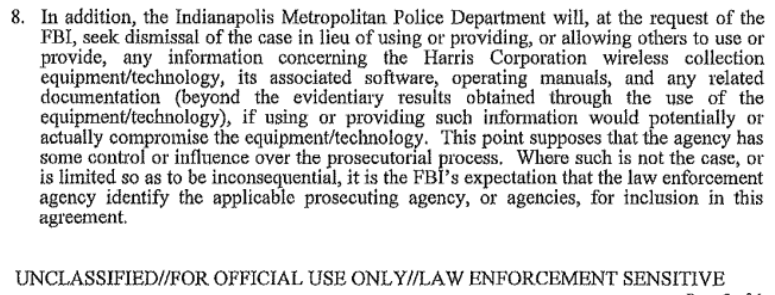

These non-disclosure agreements, dozens of which police departments have (intentionally or not) already made public, can be described as explicitly prohibiting police from discussing the use of stingrays in the broadest sense. An agreement prepared by the bureau for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department in 2012, for instance, bars police from telling anyone they acquired a stingray, including the public, the press, and “other law enforcement agencies.”

In plain English, the agreement instructs police to try to convict people of crimes using the data collected from such devices while also concealing the existence of the devices themselves from judges, defendants, and juries. Lastly, it asserts the FBI holds the right to seek the dismissal of any charges brought against a suspect if the case is likely to result in the public learning “any information” about the devices or their capabilities.

The FBI publicly acknowledged the existence of these agreements to the Washington Post years ago. Perplexingly, it is now refusing to do so a second time. Although, in 2015, an agency spokesperson told the Post that “nondisclosure agreements do not preclude police from discussing the equipment’s use.” The agreements themselves contradict that statement, and maybe the FBI now prefers silence rather than continuing to live a lie.

While the Freedom of Information Act allows the FBI to withhold certain information from the public based on the idea that doing so would compromise “techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions,” the ACLU is arguing that the agreements themselves are not covered under this exemption.

Here are 26 of them, compiled by Mike Katz-Lacabe at the Centre for Human Rights and Privacy. I’m not a lawyer, but feel free to judge for yourself.

The ACLU said on Wednesday that it launched its effort to gather copies of the non-disclosure agreements 11 months ago after Gizmodo discovered the primary company responsible for providing law enforcement stingrays, the Harris Corporation, had decided it would no longer sell them directly to local police. As Gizmodo reported, police agencies are now turning to other manufacturers, including one in Canada whose patents lean heavily on the work of engineers overseas.

“The public lacks information about whether the FBI is currently imposing conditions on state and local agencies’ purchase of cell site simulator technology from these or other companies,” the ACLU’s complaint says.

“In response to our request, the FBI issued a ‘Glomar response,’ meaning they refused to confirm or deny the existence of any responsive records,” the ACLU said. “Glomar responses are only legal in rare situations where disclosing the existence (or non-existence) of the requested records would itself reveal information that is exempt from disclosure under FOIA.”

“In this case, the FBI’s Glomar response doesn’t come close to passing the sniff test,” the lawyers said, calling the bureau’s refusal to “confirm or deny” if it even has records about secrecy agreements “ironic indeed.”

“The fact of whether the FBI has continued to impose nondisclosure agreements and other conditions on local and state police isn’t a secret law enforcement technique or procedure,” they said. “It’s basic information about whether the government is evading foundational transparency requirements we expect in a democratic society.”

The FBI did not respond to a request for comment.

The use of stingrays — so named for one of the most popular models of IMSI-catchers, a technology that’s used to track the locations of mobile phones by mimicking legitimate mobile phone towers — is not controversial exclusively due to the secrecy surrounding it. But it is a major factor. Authorities have gone to extreme lengths to conceal their existence. Prosecutors have been known to drop cases against criminal suspects because officers will flat out refuse to be questioned about the use of stingrays in court. U.S. Marshals once notoriously raided a Florida police department to seize any documents related to stingrays; an effort to keep the department from disclosing them under the state’s own public records law.

In an apparent effort to confuse judges authorizing their use, the U.S. Justice Department once circulated a template for warrant applications that misleadingly affiliated the devices with other phone tracking technologies regularly employed for over half a century. Defendants have gone to court and been convicted of crimes without the vaguest understanding of how police gathered evidence against them. To hide stingrays, police have employed a controversial law enforcement technique known as “parallel construction,” which seeks to create, as one Wired reporter put it in 2018, “a parallel, alternative story for how it found information.”

“For decades, law enforcement agencies across the country have used Stingrays to locate and track people in all manner of investigations, from local cops in Annapolis trying to find a guy who nabbed 15 chicken wings from a delivery driver, to ICE tracking down undocumented immigrants in New York and Detroit,” the ACLU said. “But until a few years ago, even the existence of this technology was shrouded in near-complete secrecy.”

We now know what’s real, even if the FBI is free, for now, to pretend otherwise.