Quetzalcoatlus, with its 12.19 m wingspan, is undoubtedly one of the most extraordinary animals to have ever lived. The creature was capable of flight, but how it managed to launch itself into the air has remained a mystery — until now.

I often wonder about the exotic forms of life that might exist on distant planets, but all I have to do is look into our own world’s past. We’ve had our fair share of freaky creatures, with Quetzalcoatlus easily cracking the upper echelons of this list. Living 70 million years ago during the Cretaceous, this gigantic pterosaur — with wings spanning 10 to 12 metres in length — is the largest flying animal to have ever lived.

Paleontologists first learned about Quetzalcoatlus in the early 1970s, but we still know remarkably little about these oversized fliers, including how they managed to take off. A monograph of five papers, all published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, is welcome news, providing the most comprehensive study of Quetzalcoatlus to date.

“To say that this work is long awaited is something of an understatement,” Darren Naish, a pterosaur expert who wasn’t involved in the new research, said in a University of Texas press release. “The good news is that it very much delivers…[as never] before has so much detailed information on azhdarchids (the pterosaur family that includes Quetzalcoatlus) been gathered in the same place, this meaning that the work will serve as the standard go-to study of this group for years — probably decades — to come.”

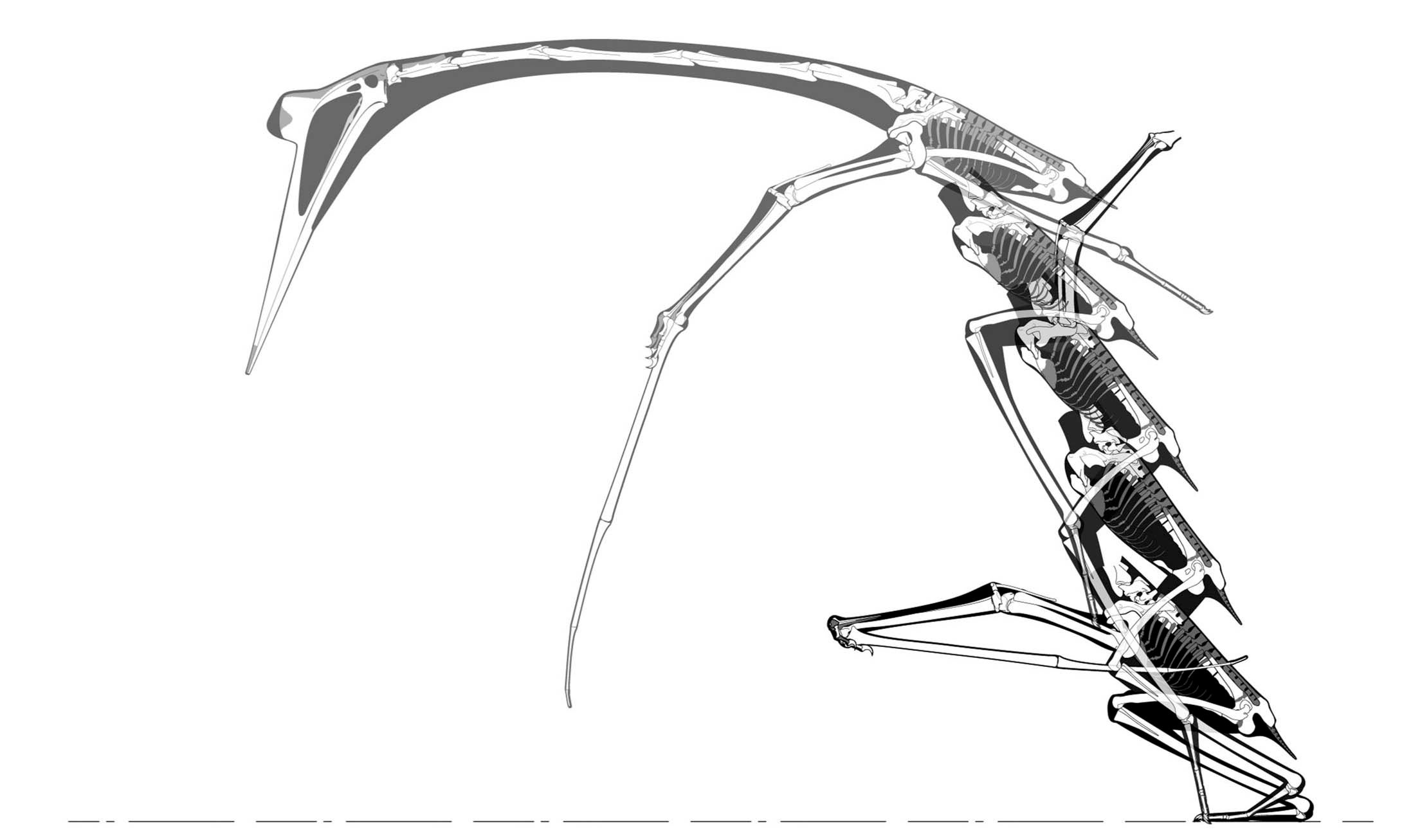

Topics in the monograph include the discovery and distribution of the species, their habitat, physical characteristics and taxonomy, an updated evolutionary family tree, and an analysis of their functional morphology, in which scientists “reconstruct the proportions and possible motions of the skeleton of the giant azhdarchid pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus.”

To date, all known and suspected Quetzalcoatlus fossils have been found at Big Bend National Park in Texas, and they’re all kept at the University of Texas at Austin’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections at the Jackson School of Geosciences. A comprehensive review of these ancient bones made the new studies possible.

Going into the new research, scientists had identified one species, known as Quetzalcoatlus northropi. Smaller bones were attributed to juveniles, but this appears to have been a mistake. As the new research shows, these smaller bones belonged to two previously unknown pterosaur species, Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni and Wellnhopterus brevirostri. The former, only the second Quetzalcoatlus to ever be discovered, was named in honour of Douglas Lawson (the paleontologist who first discovered these creatures), and it featured a wingspan between 5.6 – 6 metres.

Pterosaurs, whether large or small, “have huge breastbones, which is where the flight muscles attach, so there is no doubt that they were terrific flyers,” Kevin Padian, an emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a co-author of the functional morphology study, said in the University of Texas release. Figuring out how Quetzalcoatlus took off, however, has proven difficult, as only a few dozen bones of the larger species, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, have ever been discovered. But because hundreds of bones exist for the smaller version, the team was able to create a partial reconstruction, allowing them to make inferences about the larger one.

Previous theories suggested Quetzalcoatlus rocked forward like a bat to achieve flight, or that it built up speed like an albatross, running and frantically flapping its wings to get airborne. The new research suggests Quetzalcoatlus achieved flight through a different means, namely by crouching and then jumping some 2.4 metres into the air. Clear of the surface, Quetzalcoatlus then proceeded to flap its wings.

The scientists also studied the geological context of Big Bend, which featured a vast evergreen forest during the Cretaceous. The larger Quetzalcoatlus, according to the researchers, had a lifestyle similar to that of modern herons, choosing to hunt alone in rivers and streams. (To be clear, pterosaurs were not birds, nor did modern birds evolve from pterosaurs.) The scientists suspect a more social lifestyle for Q. lawsoni, given that their bones were found clumped together.

Quetzalcoatlus, the new studies show, were likely probers and not skimmers. Using their long toothless beaks, the creatures picked off crabs, clams, and worms lurking at the bottom of rivers and lakes.

These new studies are amazing, but there’s still plenty we don’t know about Quetzalcoatlus, such as the extent of their diet, how they walked, and how they managed to avoid predators. It’s hard to imagine the terrifyingly huge predator that could take down a giant pterosaur, but this is the Cretaceous we’re talking about. The new work represents an important next step as scientists seek to learn more about these remarkable, seemingly alien animals.