The month before a massive federal civil trial is set to begin over the horrifying “Unite the Right” march in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, one of the deadly rally’s main architects has a different priority: logging off and playing video games.

Neo-Nazi conspiracy theorist Jason Kessler is the far-right activist who obtained the permit for the rally, where many of his compatriots brutally beat counter-protesters. Infamously, white supremacist James Alex Fields, Jr. took the life of anti-racist activist Heather Heyer and wounded scores of others in a terrorist attack with a car. Afterward, Kessler threw a press conference where he appeared to threaten locals with further violence if “rational discussion” didn’t prevail before he was quite literally run out of it by angry attendees; he later tweeted that the death of Heyer was “payback time.”

Other than Fields, who is now serving life in prison, and four members of the skinhead Rise Above Movement convicted of rioting charges in 2019, most of those involved escaped without charges. But Kessler and over a dozen other rally organisers, promoters, participants, and groups — including Richard Spencer, Matthew Heimbach, Andrew Anglin, Robert “Azzmador” Ray, Christopher “Crying Nazi” Cantwell, Jeff Schoep, Fields, Vanguard America, the National Socialist Movement, Identity Evropa, and various KKK chapters — can’t dodge a long-running civil suit scheduled to go to trial next month.

The suit, which was filed on behalf of Charlottesville-area residents by a nonprofit called Integrity for America (IFA), accuses them of conspiring to violate civil rights, negligence, racial harassment, and assault. It could result in injunctions barring their future activities and massive compensatory, statutory, and punitive financial damages. The defendants countered that they were engaged in a lawful political protester protected by the First Amendment, and Kessler himself has filed several lawsuits claiming his own rights were violated by city officials who failed to prevent violence (all of which have been dismissed, though he is still appealing one verdict).

So, how is Kessler preparing for the legal fight? He’s trying to lay low online and explaining to his followers that he’d really rather focus on video gaming and lifting right now.

“I’m challenging myself to drastically reduce my social media usage over the next couple of months. Especially Twitter which is so immature and fake, everyone pretending to be something they’re not,” Kessler wrote in his channel on messaging app Telegram on Sept. 3. “… These are all attack vectors for me to be harassed and surveilled. I need to do my best to try and be a serious person and make things as easy as possible on myself and my legal team because there are more important things at stake.”

“I want to thank all of you for your support during this process,” he added. “For now, I am just trying to absorb myself in whatever I can: working, lifting weights, listening to music, playing video games, reading books, etc. Hopefully not dwelling on events to come will help the time go by quicker and give me an opportunity to grow my character by increasing temperance and patience.”

Kessler appears to have deleted his Twitter account, which the company infamously verified after Unite the Right, sometime around Sept. 1; the Internet Archive shows that it had some 3,677 tweets as of June 9. He hasn’t deleted his more obscure account on far-right site Gab, though he’s been silent on there since the end of August. Most of his other accounts, such as his ones on streaming site DLive and video site Bitchute, as well as his personal website, have similarly been inactive since the end of August. That also appears to be the last time Kessler’s writings were published via VDARE, a xenophobic anti-immigration group where he play-acts as a journalist.

Earlier this month, Megan Squire of the Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC) noted that Kessler also recently nuked a domain he set up to raise funds for the defendants’ legal costs. In total, Squire tweeted, she identified only $US164.57 ($226) in bitcoin donations that Kessler received through the site. (A separate fundraiser on evangelical Christian fundraising site GiveSendGo, a haven for right-wing extremists, has raised $US15,000 ($20,588) of a $US100,000 ($137,250) goal.)

“The dilemma for the propagandists who hyped Unite the Right is that they need to say things online that can potentially get them into big trouble, just to do their activism in the first place,” said Michael Edison Hayden, a senior investigative reporter and spokesperson for the SPLC.

This isn’t the first time Kessler has deleted his Twitter account. Tweets show that he took the account offline on Aug. 19, 2017 (around the time of the “payback time” tweet, which he first claimed was due to a hacker and later blamed on a combination of prescription drugs and alcohol) and again in November 2019, only to return both times. Other users on Twitter have noted many occasions in which Kessler deleted tweets, allegedly to remove slurs or simply to cover his tracks. On other occasions, associates of Kessler have tried to distance themselves from him by doing the same, such as right-wing site the Daily Caller, which deleted three articles he contributed to the site after the Charlottesville rally.

It’s a futile gesture. The internet may have a far shorter memory than is commonly assumed, but anti-fascists tracking the far right and the plaintiffs in the looming lawsuit have extensive archives of Kessler and the other defendants’ online histories. The amended complaint for the looming lawsuit, Sines v. Kessler, contains numerous examples of Kessler and his ilk preparing for violence on the days of the rally on chat app Discord — particularly in a Discord server called Charlottesville 2.0 run by Kessler and Elliot Kline (aka Eli Mosley) that just so happened to have been infiltrated by the left-wing media collective Unicorn Riot.

the exhibits are described in the list but not pictured or dated, but there are some very interesting hints buried in these 53 pages pic.twitter.com/z36l3P8zCw

— molly conger (@socialistdogmom) September 15, 2021

The plaintiffs in the suit are relying on an obscure civil rights statute in the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. Attorney Karen Dunn, one of the lawyers behind the suit, said in a panel that the law “was originally designed to protect the rights of people in the Reconstruction era and, as others have said, what we have alleged here is a conspiracy to do racially motivated violence, which is not lawful or protected speech.”

One court document, a plaintiffs’ expert report, states that early in the planning stages for the rally, Kessler posted to Discord expressing his intent to create a “Battle of Berkeley situation in Charlottesville” and stage a “showdown with antifa,” as well as inviting violent groups he acknowledged would be “difficult to say that you can contain.” According to the complaint, Kessler and Kline’s Charlottesville 2.0 server provided attendees a space to organise transportation, coordinate plans, and distribute promotional material often calling for violence, the archives of which may ultimately prove their undoing. Kessler and Mosley also allowed various far-right groups such as Vanguard America, Identity Evropa, and the Traditionalist Workers’ Party to have their own private channels on the server, the suit claims.

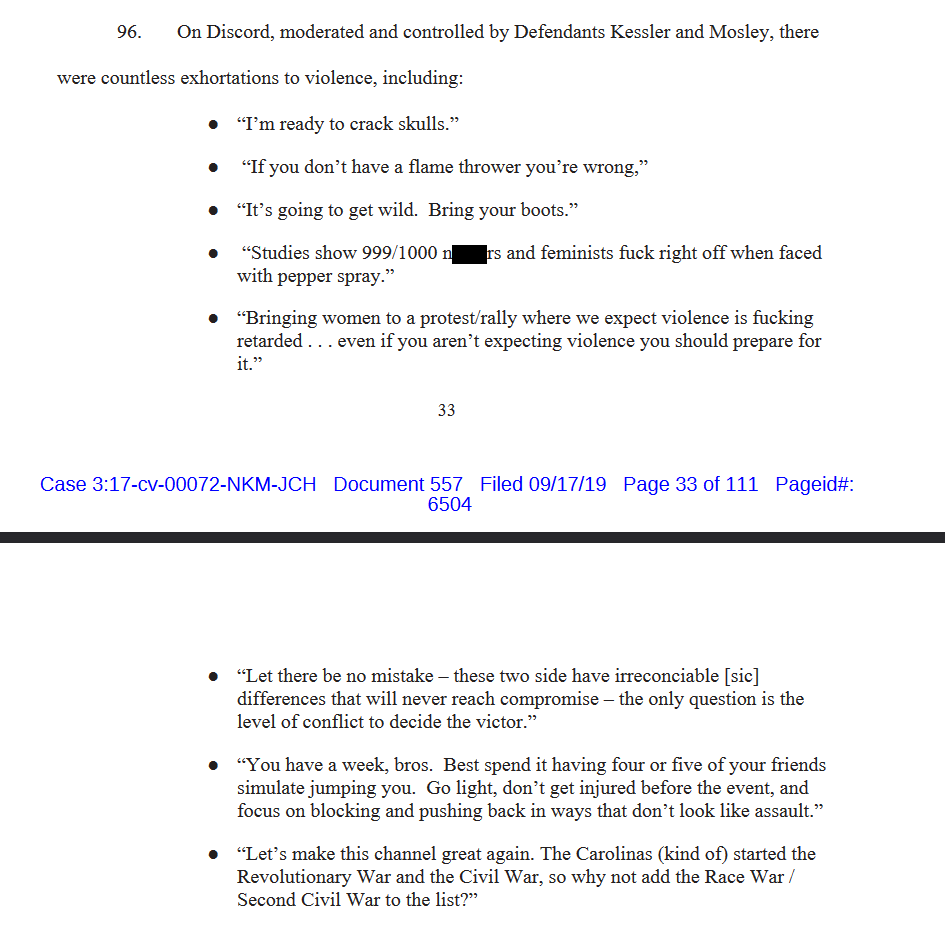

The plaintiffs say records of the server are damning and demonstrate “countless exhortations to violence”:

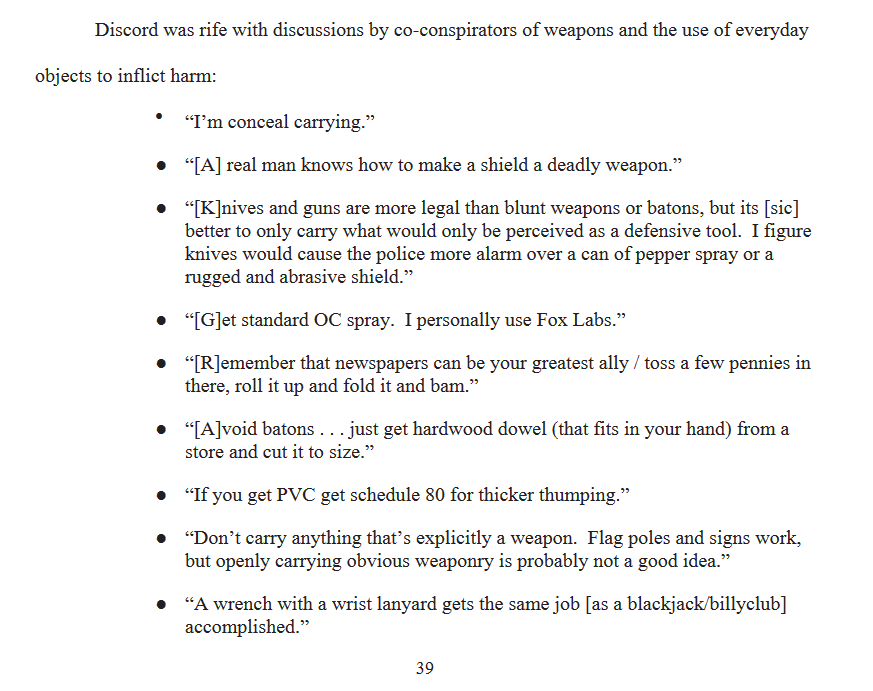

In “General Orders” distributed via the Discord obtained by the plaintiffs, Mosley allegedly referred to “Enemies/Counter Protesters” as “hostile” and warned that if they lost their permit, they may resort to “plan red.” The plaintiffs say numerous posts on the server told attendees to bring firearms, other weaponry, and body armour to the event, with one user allegedly writing that plans to arm up were “discussed with the organisers.”

Kessler himself allegedly posted in an #announcements channel, “@everyone . . . I recommend you bring picket sign post, shields and other self-defence implements which can be turned from a free speech tool to a self-defence weapon should things turn ugly.” In another post on Discord, Kessler allegedly said anyone who “[wants] a chance to crack some antifa skulls in self-defence” shouldn’t openly carry a firearm, as it might “scare the shit out of them and they’ll just stand off to the side.”

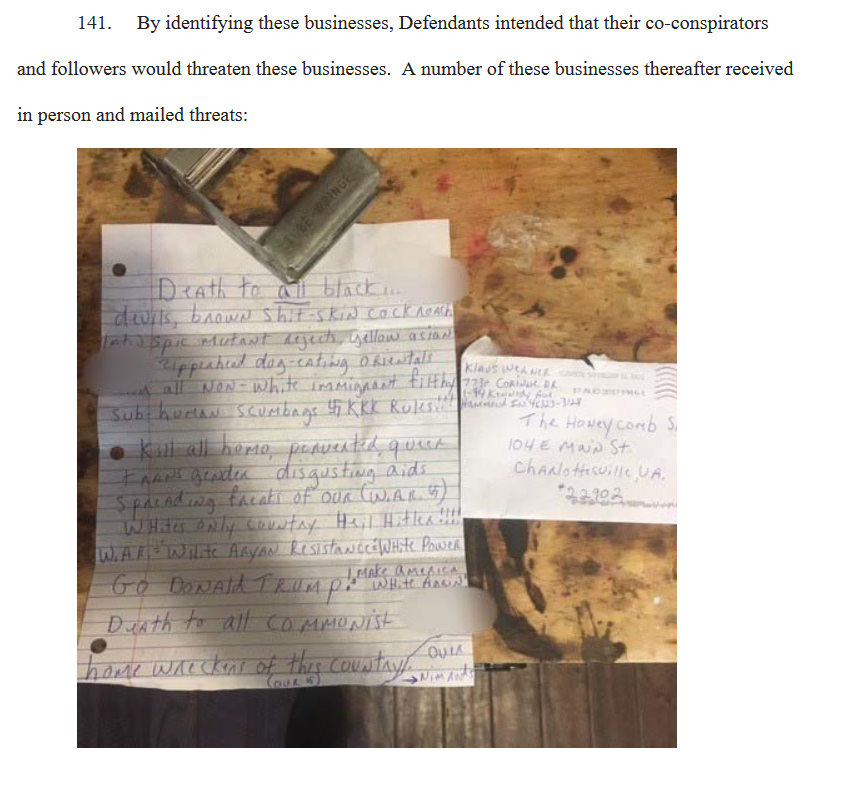

According to the complaint, Kessler also released a video targeting a Charlottesville-based anti-racist religious organisation, Congregate, and urged Discord users to identify local businesses that had opposed his permit. Some of those businesses later received threats in person or via mail, the plaintiffs wrote.

One archived tweet shows Kessler celebrating the infamous tiki torch march on the night of Aug. 11, where the complaint says many attendees turned violent and urged other Discord users to “defend our territory” on the day of the attack.

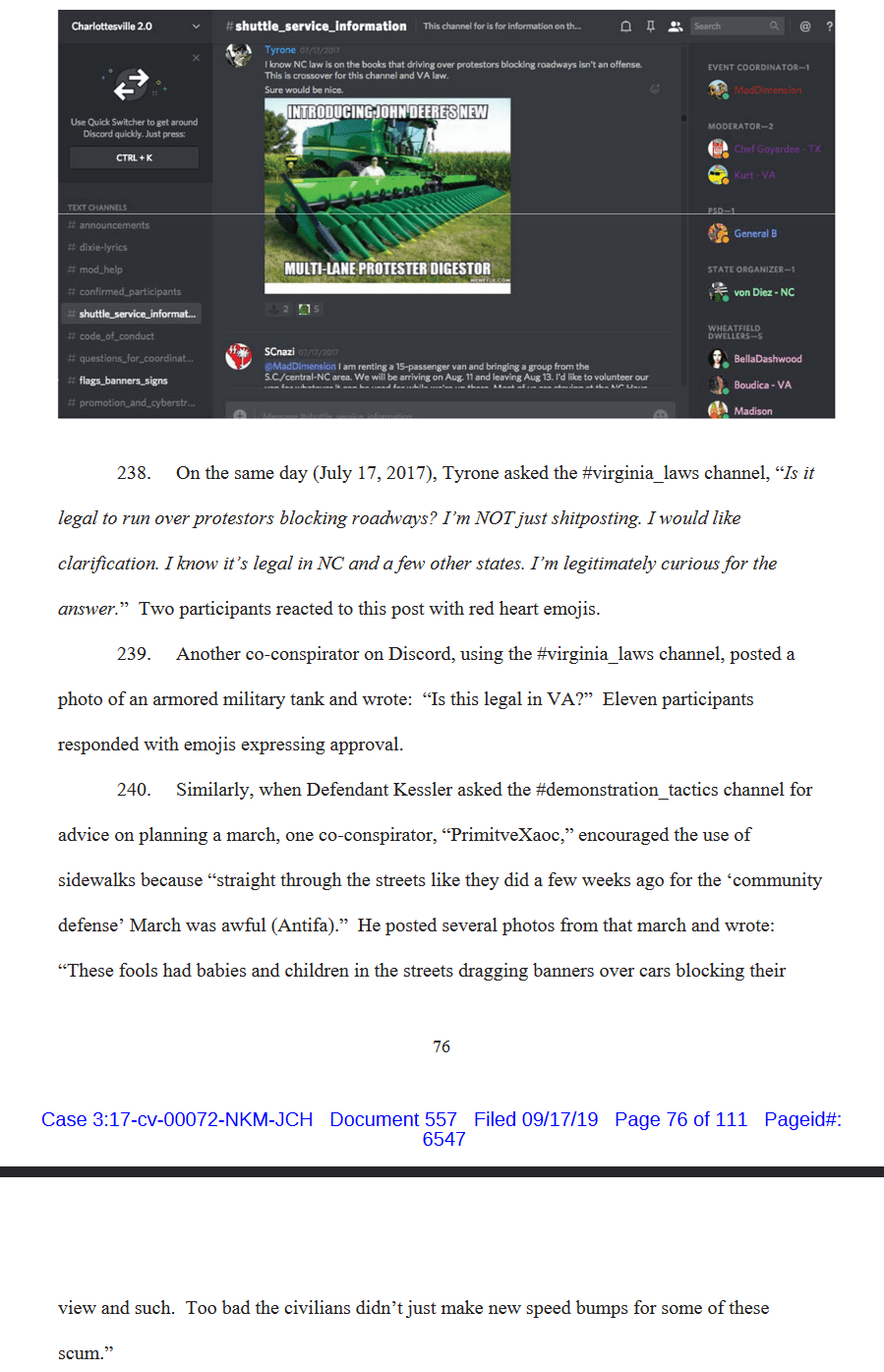

The suit also details discussions on Discord to organise waves of attacks on counter-protesters. While there’s no evidence Fields was part of the server, the plaintiffs’ complaint provided examples of users discussing the ideas of car attacks on protesters and inquiring about whether running over people blocking the street was legal in Virginia.

“Their ideology is inherently violent and terroristic, no matter what they say otherwise. It’s based on a goal of upending our society and eliminating multiculturalism altogether,” Hayden, the SPLC reporter and spokesperson, told Gizmodo. “And since that message appeals to other angry men who fantasize about attacking society, inflicting pain on people, everything the propagandists say online has the potential to become something that they one day regret. Even if they ultimately regret it for selfish reasons, like legal trouble or losing access to social media.”

The backlog of evidence is just one reason Kessler might want to focus on video gaming right now. According to the New York Times, the defendants aren’t doing very well in pre-trial proceedings. Spencer’s lawyer quit the case last year after Spencer stopped paying. The court has already issued sanctions against some of the groups involved, such as one against the National Socialist Movement for allegedly destroying evidence, and the plaintiffs won adverse inferences against defendants including Robert “Azzmador” Ray, Mosley, and Vanguard America.

IFA lead attorney Roberta Kaplan told the Detroit Jewish News this month that the suit seeks “justice for the plaintiffs through monetary claims against the defendants and deterrence to other groups considering such things.”

“By winning large financial judgments at trial, we can effectively bankrupt and dismantle the leaders and hate groups at the core of the violent, antisemitic white supremacist movement and make clear the consequences for this violent hate,” Kaplan added.

Gizmodo reached out to Kessler for comment on this article and we’ll update if we hear back.