Neon Genesis Evangelion has ended. It’s done this before, of course — it’s done it several times, from its original TV series to its movie continuation End of Evangelion, its manga adaptation, and now, with the release of 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time, its “Rebuild” theatrical self. To end Evangelion is no longer a radical concept, and yet its latest feels definitive and radical in a way like no other for the way it matures the franchise’s most enduring thesis.

Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time is a film as weighty and obtuse as its name might seem incomprehensible to anyone who has gone the past 26 years without dipping into its apocalyptic world of traumatised teenagers and giant technorganic robots. As a film, it is tasked with the inexplicable burden of ending not just the four-part theatrical remake of one of the most beloved and debated anime series of all time, but bidding farewell to the series in totality as creator Hideaki Anno’s final word on Eva — the forever reminder that Death of the Author and Evangelion are concepts that feel impossible to exist in concert with one another.

At points in its two-and-a-half-hour runtime, it threatens to buckle under the sheer burden of a generation’s worth of expectation. A first act of placid, slice-of-life drama about finding peace in a world torn asunder by the apocalypse gives way to a second act: incomprehensible fights and equally incomprehensible theology, as explosions and proper nouns alike fly past, through, over, and under the audience with equal parts dazzling speed and reckless abandon.

By the time it has set up its final end — the ur-conflict of all Evangelion, the struggle of teen pilot Shinji Ikari to understand his megalomaniac father Gendo — Thrice Upon a Time has invoked so much of the Evangelion that came before it that you struggle to wonder what more it could add, what new it could say for one last time. It’s perhaps telling then, that its true ending is not necessarily a new idea, but a maturation of the hopeful message that Evangelion’s dark story has always had, in spite of its reputation.

Battling his father mecha-to-mecha, each wielding the theological spears of Longinus and Cassius, described as literal embodiments of the concepts of Despair and Hope, Shinji declares that his choice between the two is not one or the other, but simply both. Shinji has attempted to confront his father’s distant relationship with him many times over the course of the series, but there’s something different about him here in this latest confrontation. He understands the traumas that he has lived through, and come to terms with them to realise that there is a future for him to look forward to where he can be happy.

At peace with the reckoning he has made for himself over the course of his long road to self-actualisation — his purpose as a son, his purpose as an Evangelion pilot, his purpose as a human being in the world — Shinji instead decides that the answer isn’t to fight Gendo, but, at long last, attempt to understand him, to find common ground in the griefs and lives they have both endured, ones lived far apart from each other until now. Able to help his father overcome the debilitating grief of losing his wife, the one person Gendo could connect with beyond his own child, Shinji convinces his father to help to combine Longinus and Cassius into a singular weapon.

With the power of newly-forged Gaius, Shinji helps the people he’s dared to care for most in his life with their own journeys to understand themselves. The Rebuild of Evangelion becomes literal, as Shinji’s way to facilitate that connection with his loved ones is to crucify the apocalyptic machines and use their undoing to rebuild the world into one where Evangelions never existed in the first place.

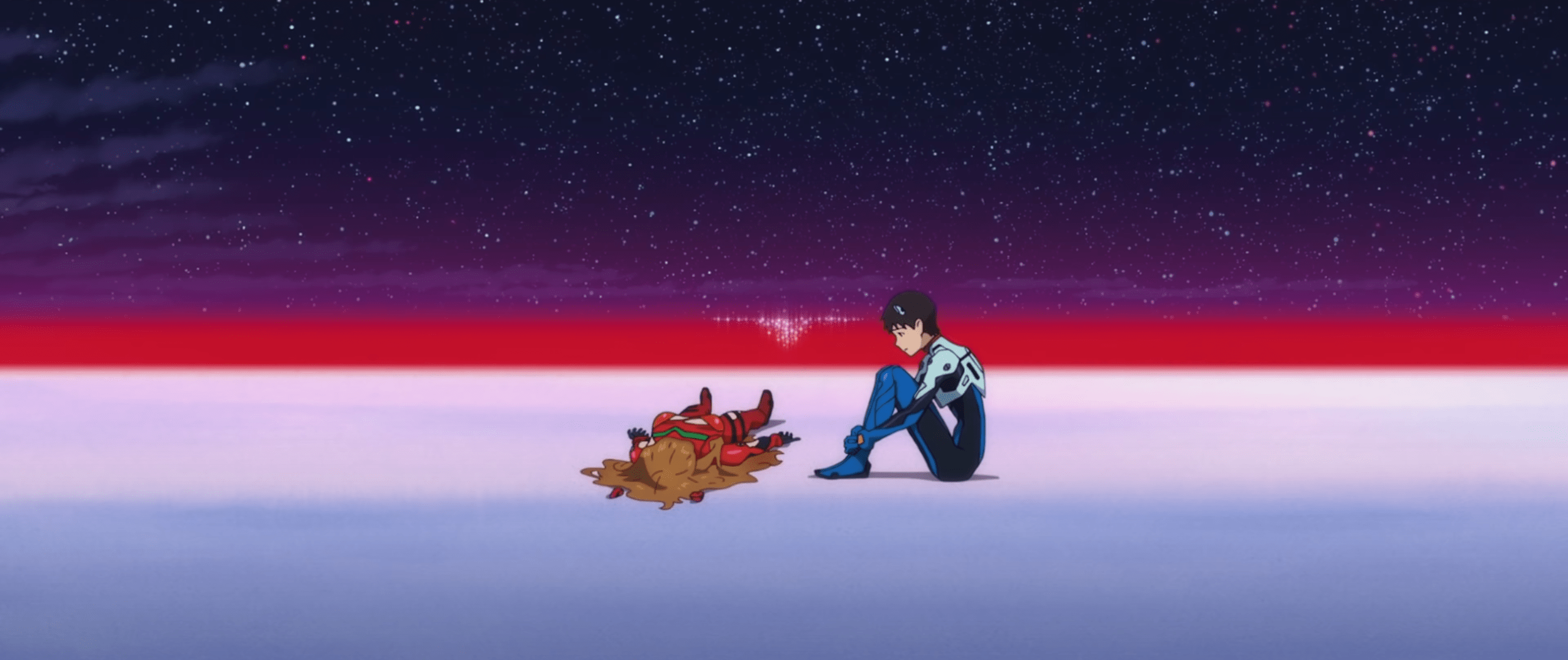

As Shinji hops through the dying breaths of a universe, where lines of what is text and what is metatext blur — an anti-verse negative space here, a half-drawn beach there, even a literal rendition of the motion capture stage several scenes of Thrice Upon a Time was shot on — he touches on his relationships with the family and friends he’s made along his journey.

He reflects on the spirits of his father and mother, the closest things he has to friends in fellow pilots Asuka and Rei, his intoxicating and intimate connection with the Angel Kaworu Nagisa, and ultimately his understand of himself. In the end, he waits to be pulled from this dream space into a new world not by his own understanding, but crucially by a new connection of his own, in the form of Rebuild’s most cryptic addition, the Eva Unit 08 pilot Mari Makinami Illustrious.

Each goodbye is filled with Shinji’s own understanding of who he is, and his choice to believe in a better world beyond the suffering endured in the worlds of Evangelion. But crucially they are also filled with him making the effort to reach out and tell each of these people he cares about them, and the sincerity in his desire to help them come to terms with their own traumas.

What we are left with after Shinji makes these radical acts of compassion the pathway to his “Neon Genesis” — the birth of a new world — is a world that, well, looks much like our own. Thrice Upon a Time closes in an animated rendition of a train station in Hideaki Anno’s hometown, Ube, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Shinji, Kaworu, Rei, Asuka, and Mari are all there and grown-up, the curse of the Evangelions that rendered them perpetual teenagers, locked into the traumas of their childhood upbringings, now broken.

It’s left to the audience to wonder if, outside of Shinji and Mari, they all still know each other, or if they are simply people who have grown up and moved on with their lives individually. But they are alive, at least, and seemingly happy.

Thrice Upon a Time’s final message, as Shinji and Mari run out of the station and into a new life together — as the animated backgrounds give way to real-life footage of the station and surrounding town — is that the peace these characters have found was brought about by being open and understanding to each other. Our heroes are allowed to heal, to move on from the hurt that defined them as we once knew them, and say goodbye to Evangelion forever.

There can be no more Evangelion, for the ultimate power of this world, of our own, is not a legion of building-sized deified cyberorganic metaphysical weapons of Man and God, but our ability to be open with others, to care for them, to forge sincere, loving bonds with one another. This boundlessly hopeful ending is not in contrast with the ends that Evangelion has faced before, it’s in conversation with them.

It’s a continuation and maturation of a hope that has woven the entire franchise together for decades, often in spite of Eva’s burdensome reputation as a subversive, gritty, and cumbersomely edgy metacommentary on mecha anime as a genre.

The original ending of Neon Genesis Evangelion, the product of budgetary constraints, tight deadlines, and Anno’s own depressive state, is an artistic, unabashedly beautiful message of Shinji overcoming his doubts to self-actualise and to love his own reckoning as a person.

The widespread backlash to that conclusion brought us the movie End of Evangelion, a vision of the original series’ climax presented through a much darker, cynical lens. Although as spiteful and nihilistic a film as it can be, the movie’s ultimate conclusion for Shinji is much the same hope as the show’s, even if it is tempered by the harsh truth that admitting your self-actualisation and openness to care for yourself will be challenged by others as insincere or childish in an unforgiving world — or even disgusting, as the catatonic Asuka says of Shinji in End of Evangelion’s final moments.

And so when we come to Thrice Upon a Time’s extrapolation of that challenge, we find its message echoed, but also evolved — that self-actualisation to heal oneself is but a step on the journey, but true hope is made in reaching out to others, to help them heal as you have as well. It’s the ultimate expression of hope as a concept in Evangelion at large, something that has always been at the heart of Evangelion.

But in growing the idea of that from a strictly personal realisation to a communal one, Thrice Upon a Time’s farewell to Evangelion as a story shines as perhaps the most hopeful of all its conclusions. A fitting end to Eva as both we and its heroes know it — in letting go of it as a shared experience over these past 26 years, we must learn to be open with each other beyond the connection it gave fans place in order to truly grow.