The longest biological experiment ever performed on the International Space Station has exposed the surprising durability of freeze-dried mouse sperm when exposed to space radiation.

The year is 2189. With the launch of Generation Starship Tycho just months away, the pace of preparations had taken on a frenetic pace. Operations manager Prisha Tengku was finalising the installation of 10 exosomatic womb chambers when she noticed a strange box tucked away in the corner of the cryogene lab. Curious as to its contents, Tengku examined the box, finding 10 glass ampules filled with a whitish substance. Labels identified the canisters as holding freeze-dried human sperm, which had been prepared in the year 2038 and kept aboard Lagrange2 Space Station III since that time.

Tengku was immediately tempted to throw out the 151-year-old samples. There’s no way, she thought, that sperm exposed to space for so long could possibly survive all that radiation. What’s more, the freeze-dried samples were stored at room temperature, with no special protective casing. Smartly, however, she decided to check the literature to see if an expiration date existed for this sort of thing. Nothing in the recent scientific literature came up, so she broadened her research, resulting in the discovery of an obscure paper from 2021 that appeared in Science Advances.

The paper, co-authored by Teruhiko Wakayama from the Advanced Biotechnology Centre at the University of Yamanashi in Japan, describes an experiment in which freeze-dried mouse sperm remained viable after spending nearly six years aboard the International Space Station. Ionizing space radiation is known to damage cellular DNA, triggering potentially deleterious inheritable mutations. The researchers aimed to determine the long-term effects of space radiation on mammalian sperm kept on the International Space Station and how this exposure might affect normal reproduction.

This was the same orbital station, Tengku chillingly recalled, that was annihilated by errant space junk in 2029. She paused, realising that Wakayama and his colleagues were doing important work, setting the stage for long-term space missions to the Moon and Mars — and now the impending launch of Generation Starship Tycho to interstellar space. Digging deeper, Tengku found a June 2021 interview with Wakayama, in which he wrote to Gizmodo science reporter George Dvorsky in an email.

“Hundreds of years from now, when humans live on another planet, we will have to bring domesticated animals, such as dogs and cats,” Wakayama wrote. “To maintain those species or strains, we will have to bring a lot of animals to avoid inbreeding, but it will be too expensive. However, if you bring freeze-drying sperm — and oocytes if possible — you can maintain such species without the cost for transportation.”

Theoretically, the same strategy could apply to humans, should future space explorers require a safe, cheap, and convenient way of storing sperm.

It isn’t easy to study this sort of thing, as the ISS has a dearth of freezers, and hauling tanks of liquid nitrogen to space is costly and onerous. Instead, Wakayama and his team got the idea of freeze-drying mouse sperm as a substitute, as these samples can be easily stored at room temperature, and they wouldn’t require the constant attention of astronauts. The unprotected samples simple sat on the space station for years, slowly absorbing space radiation.

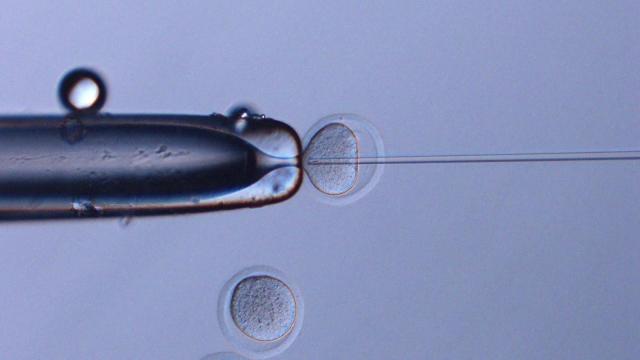

The freeze-drying process used in the study “is similar to instant coffee, or freeze-dried fruits,” Wakayama explained. “You just have to add water,” and it can be used “immediately.” The freeze-drying process kills the sperm, but when rehydrated and injected into a mouse egg, the sperm can still fertilize the egg, which then develops normally, he said.

For the experiment, the freeze-dried sperm samples of 12 mice were shipped to the ISS in small, lightweight capsules. Identical samples, which served as the controls, were stored at the Japanese Space Agency’s Tsukuba Space Centre under similar conditions, save for exposure to space.

In 2014, exactly nine months in, some samples were returned to Earth to determine if the experiment was working, which it was. Another batch was returned to Earth after two years and nine months, and the final batch after five years and 10 months, which happened in 2019. It’s the longest biological experiment ever performed on the ISS.

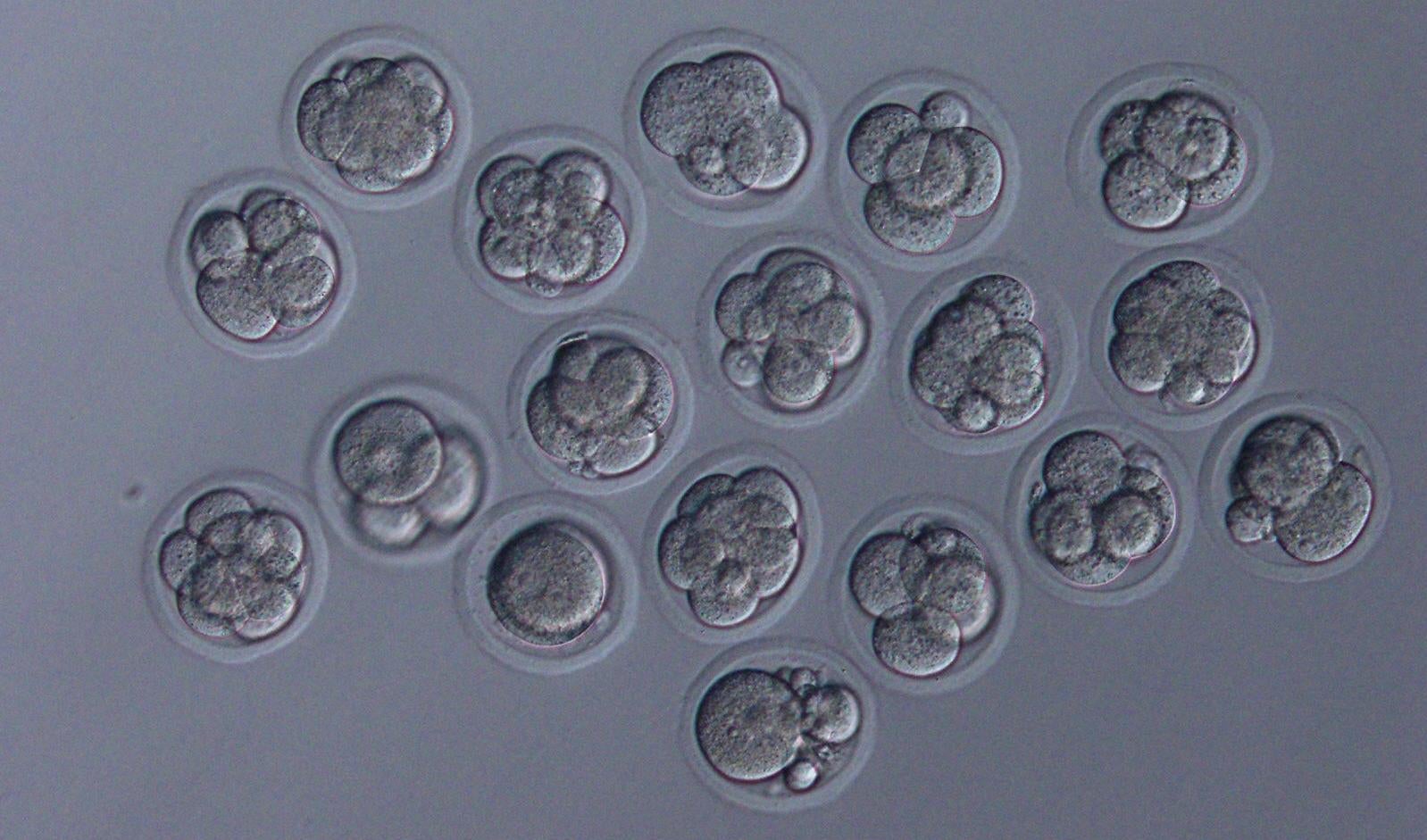

Back on Earth, Wakayama and his colleagues studied the sperm, measuring the amount of radiation the samples had absorbed. They ran tests to see if the DNA in the nuclei of the sperm had incurred any damage, finding that the radiation had a tiny effect. Embryos produced by the rehydrated sperm cells were slightly lower in quality compared to the controls on Earth, but, amazingly, they developed into 168 baby mice, who all appeared normal. Further analysis of the baby mice with RNA sequencing tools showed no abnormalities in genetic expression. Some of these mice were raised to maturity and were able to produce healthy babies of their own.

The team also performed a control experiment on the ground, in which the freeze-dried sperm were exposed to X-rays. This experiment showed that freeze-dried sperm “has a strong tolerance against radiation,” said Wakayama. This result, combined with the findings from the ISS experiment, lead the team to conclude that “sperm can be preserved for at least 200 years on the ISS,” as he explained.

With this experiment complete, Wakayama is already looking to perform similar experiments on NASA’s proposed lunar Gateway space station, planned to be put in orbit around the Moon.

“In space, there are two different environments: one is space radiation and the other zero gravity … and we want to know whether mammalian embryos can develop under zero gravity or not,” he said, adding that the proposal for this experiment was approved by NASA and JAXA back in 2015. He noted that early stage frozen mouse embryos are set to be launched to the ISS in August 2021, which astronauts will thaw and culture under zero gravity. Wakayama said he “cannot wait” to see the results of this experiment.

Her research into the matter finished, Tengku once again considered her 151-year-old freeze-dried sperm samples. As the old Science Advances paper suggested, they should still be ok and even last for another 50 years. Decades later, when G.S. Tycho was still en route to exoplanet Kepler-452b, Tengku used these samples to produce the crew’s Wallace Population, but that’s another story.