A radiological examination of a 2,000-year-old mummy presumed to be a male priest shows it’s actually the preserved remains of a woman — and a pregnant one at that.

New research in the Journal of Archaeological Science documents the “first known case of a pregnant embalmed body,” as the archaeologists, led by Wojciech Ejsmond from the Warsaw Mummy Project, write in their study.

Originally dubbed “mummy of a lady,” the linen-wrapped body was donated to the University of Warsaw in 1826. During the 1920s, and then again in the 1960s, hieroglyphics on the coffin were translated to “Hor-Djehuty,” which corresponds to the name of a male Egyptian priest. Radiological scans made in the 1990s further reinforced the interpretation of the mummy as being male, but the “current research proves that the sex of the mummy is undoubtably female,” as the archaeologists write in their study.

Indeed, this could be a classic case of the mummy not being in its original coffin, which happens on occasion. The authors of the paper “can only speculate that the mummy was placed in a wrong coffin by accident in ancient times, or was put into a random coffin by antiquity dealers in the 19th century.”

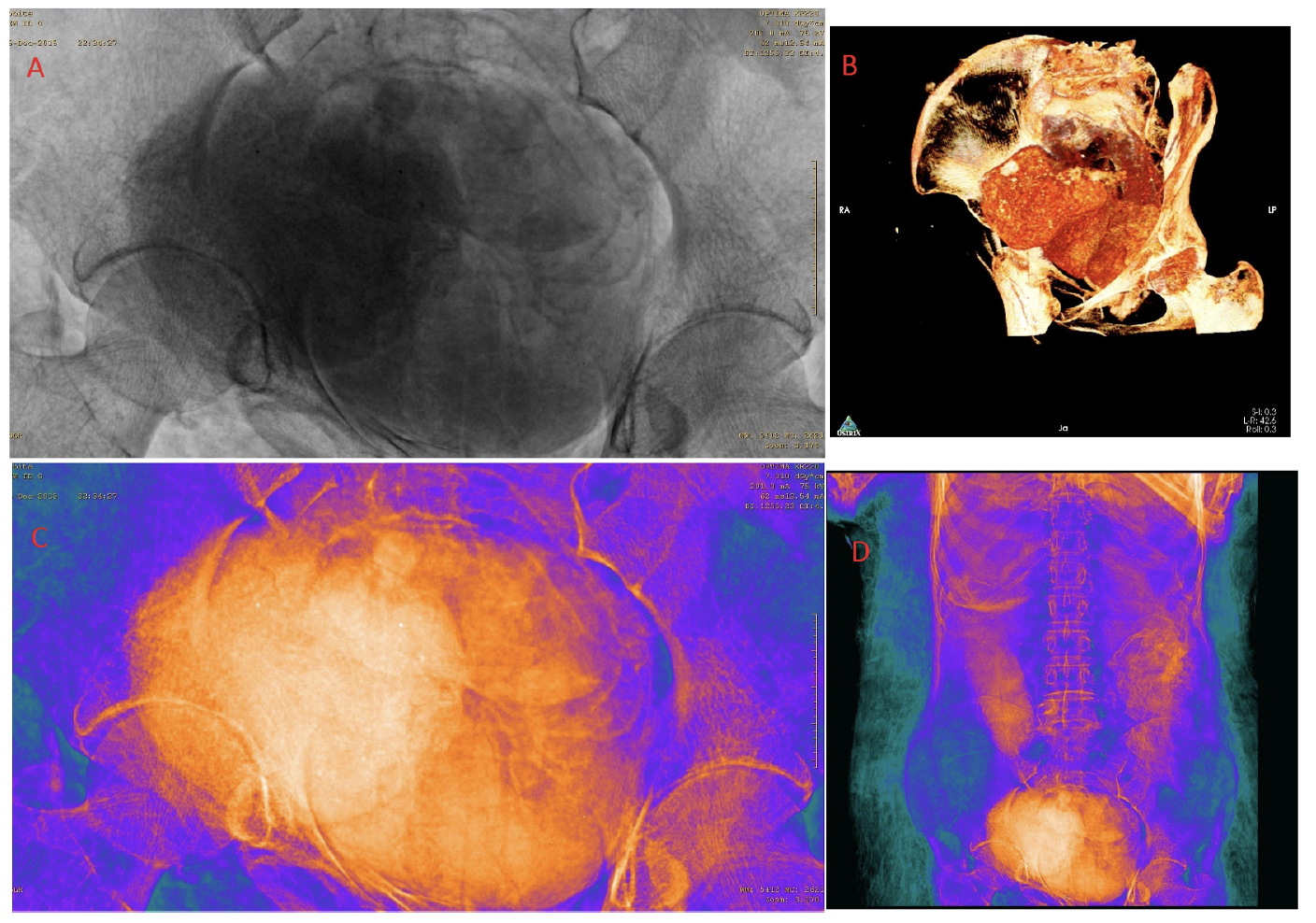

Noninvasive X-ray and CT scans confirmed the mummy as female. The archaeologists were re-examining the specimen in hopes of learning more about what was hidden behind the wrappings, as well as to conduct a dating analysis and search for signs of disease, as Ejsmond explained in an email.

But in addition to unexpectedly detecting breasts and female genitalia, the researchers spotted something far more unusual and noteworthy: a foetus.

“It was an absolutely unexpected find!” wrote Ejsmond. “At the beginning we were not believing our eyes, and we consulted other specialists who confirmed our discovery.”

Located within the mummy’s pelvis, the foetus “was mummified together with its mother,” and it was “not removed from its original location,” write the researchers.

Measurements of the foetus’s head suggests it died between the 26th and 30th week of the pregnancy, which is between the late second and early third trimester. It’s highly likely, therefore, that this woman’s pregnancy was recognised. Owing to the “poor state” of the foetus, including shrunken bones caused by drying, it was not possible for the team to measure other parts of its skeleton.

Examination of the mother’s teeth suggests she died when she was 20 to 30 years old. The origin of the mummy was traced to the royal tombs in Thebes, so it’s likely this woman was an elite member of the Theban community. Her remains were carefully mummified, wrapped in fabrics, and adorned with “a rich set of amulets,” according to the paper. The archaeologists dated the mummy to the 1st Century BCE.

Mummified fetuses from ancient Egypt have been found before (see here and here), but why pregnant mummies should be so rare remains an unanswered question. The researchers did offer some clues.

“It is very difficult to detect a foetus within an embalmed body because the bone density at this stage of fetal life is tiny and it can be easily overlooked,” explained Ejsmond. “One needs to use very good equipment to detect a foetus. This may explain why such discoveries were not reported by other researchers.”

As to why the foetus was not extracted during the mummification process, Ejsmond speculates that it was likely difficult to extract the foetus due to the “hardness of the uterus,” or because of “religious reasons,” the nature of which “we can only speculate.”

Looking ahead, the scientists would like to better evaluate the health of the woman at her time of death, which they’ll try to do by sampling a tiny amount of tissue. What’s more, this mummy could provide “new possibilities for pregnancy studies in ancient times” and shed new light on an “unresearched aspect of ancient Egyptian burial customs and interpretations of pregnancy in the context of ancient Egyptian religion,” according to the paper.

Future investigations of this mummy could provide some important clues.