An international exercise to simulate an asteroid striking Earth has come to an end. With just six days to go before a fictitious impact, things don’t look good for a 298 km-wide region between Prague and Munich.

Two years ago, the organisers of this event accidentally destroyed New York City, and now it’s time for a border region intersecting Germany, Austria, and Czech Republic to meet the same fate. When I covered the early days of this week’s simulation on Wednesday, the gathered experts were weighing their options as a 140 metre-wide asteroid barrelled toward Central Europe.

This may sound like a grim role-playing game, but it’s very serious business. Led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Centre for Near Earth Object Studies, the asteroid impact simulation is meant to prepare scientists, planners, and key decision makers for the real thing, should it ever occur. The tabletop exercise began this past Monday, and it’s happening virtually at the 7th IAA Planetary Defence Conference, which is being hosted by the UN’s Office for Outer Space Affairs with help from ESA.

“Practice and training for different situations is an important part of preparedness, whether it’s done by medical professionals or sports teams or artistic performers,” Andy Rivkin, a research astronomer at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, explained in an email. “For planetary defence, this is our chance to get people together with different expertise who don’t often get the chance to work together and look at different scenarios. This can help greatly in identifying important issues that we might not identify while working as small groups or individuals.”

Rivkin, who participated in the event, is the co-leader of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, which aims to smash a spacecraft into asteroid Dimorphos in late 2022 (for real). By crashing into an asteroid, a kinetic impactor like DART can “change the arrival time of the asteroid so it doesn’t arrive at the crossroads the same time as Earth, Rivkin said, adding that his group is testing what “happens in detail when you change the speed of an asteroid,” in this case Dimorphos.

A distinguishing feature about this year’s simulation is that the asteroid came out of the blue, so to speak. Named “2021 PDC,” it was discovered just six months before its scheduled rendezvous with Earth. The odds of an impact were initially assessed at 1 in 2,500, but that was bumped to 1 in 100 during the first day of the simulation. By Day 2, the odds were ramped up to a full 100%, with the impact site identified as being in Central Europe.

For me, a key takeaway from this year’s simulation was the dramatic way in which key variables, such as the probable impact area and affected population size, were affected by new observations. At one point, for example, North Africa, the UK, and much of Scandinavia were inside the possible strike zone.

The participants in the simulation deemed it impossible to deploy a mitigation effort, such as a kinetic impactor or nuclear bomb, given the short timeframe — a consideration not lost on planetary geologist Angela Stickle, another DART team member who participated in the exercise.

“The timeline for deflection is important,” explained Stickle, leader of the DART impact modelling working group, in an email. “Kinetic impactors work best when they are done years in advance, so the small push that you give has enough time to really change the incoming orbit away from the Earth, so even if we could have launched a kinetic impactor spacecraft like DART in the tabletop exercise scenario, we might have been too late to really steer it off course.”

Previous tabletop exercises provided many years of warning time, but not this one. Accordingly, the focus of exercise was geared toward the disaster response and the importance of identifying dangerous asteroids in advance.

For Andy Cheng, chief scientist and DART investigation team co-lead at Johns Hopkins, the teachable moment came when they all learned that the fictitious asteroid had actually zipped past Earth seven years earlier, but it wasn’t discovered “because there were not ground- or space-based telescopic assets in place that would have discovered it,” he explained in an email. Had it been detected back then, “there would have been more than sufficient warning time to mount space missions to characterise it and to mitigate the threat,” such as with a DART-like mission.

Accordingly, the tabletop simulation became an exercise in predicting the possible damage that might be inflicted by the asteroid and where that damage might occur. This wasn’t an easy task, given many uncertainties about the offending object, such as its size and physical makeup. Initial estimates placed the asteroid at between 35 metres and 700 metres in length, followed by a more refined estimate of 140 metres, which “significantly reduces the worst-case size and corresponding worst-case impact energies,” according to the Day 3 report.

Which brings us to the final day of the exercise (turns out this was a four-day project, not five days as was originally reported). Day 4 takes place on October 14, 2021 — just six days before impact. With the impact now imminent and the fake asteroid plainly in sight, the dreadful predicament became clear.

The fictitious impact would occur on October 20, 2021 at 17:02:25 UTC, give or take one second. This level of precision is really fascinating, and it demonstrates the high degree to which we’d be prepared for that fateful moment, allowing people in the affected and surrounding areas to evacuate or take cover.

Images taken by the Goldstone Observatory the day before constrained the size of the asteroid to 105 metres across. It was not as big as feared, but still big enough to cause serious damage. For Mallory DeCoster, a systems and mechanical engineer and DART investigation team member from Johns Hopkins who also participated in the exercise, the ongoing uncertainty about the asteroid’s size proved troublesome.

“We know that one of the most critical pieces of information for decision makers is high-fidelity information about the size of the asteroid,” she said. “In the hypothetical impact scenario, we saw that current instrument capabilities left us with quite a large range of possible sizes for the asteroid, ranging from a low-threat 30 metre diameter to a continent-exploding 700 metre diameter. This showcased how important it is to invest in instruments such as ground-based radars and space-based infrared sensors to provide high-resolution characterisation metrics.”

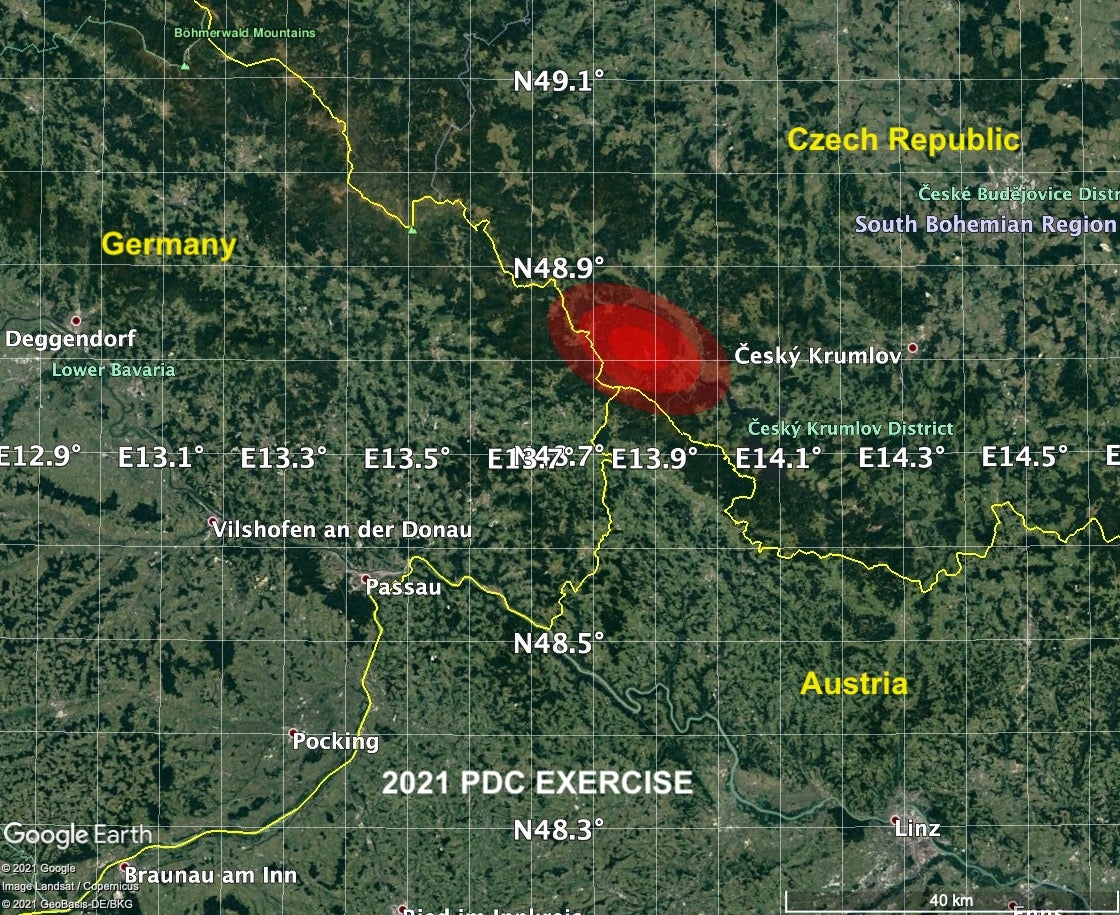

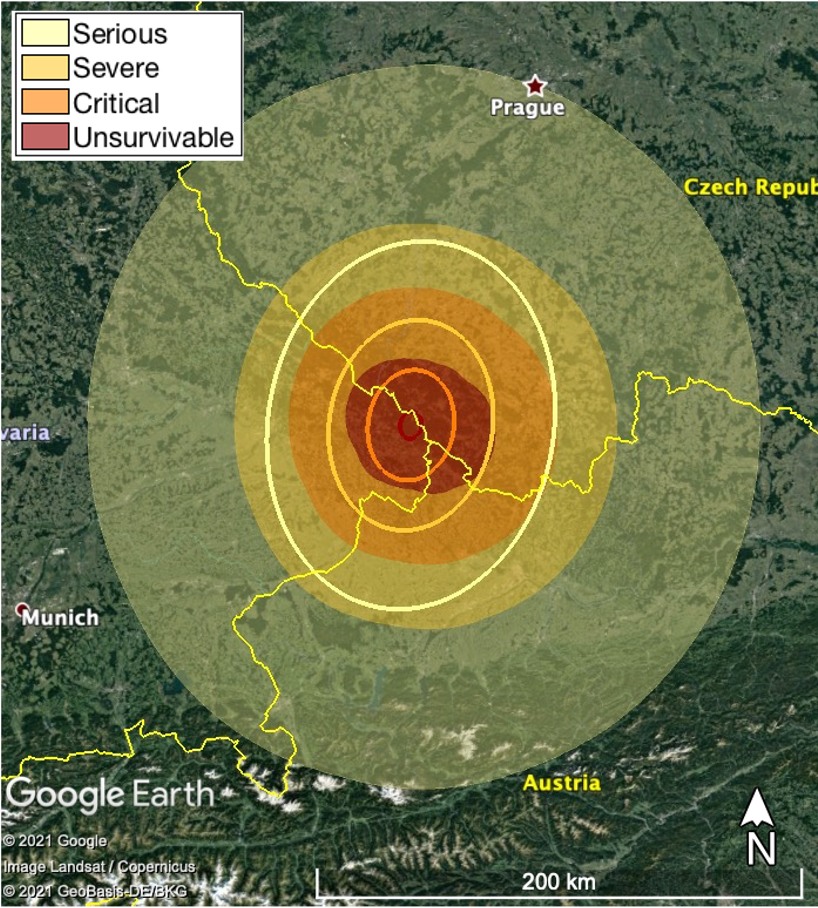

The fake asteroid was projected to strike Earth at speeds reaching 16 km per second, or 54,718 km per hour. Ground zero was predicted to reside within a 23 km range, but this number was expected to shrink by half in the coming days as the asteroid got nearer. The impact site was centred near the borders of three countries: Germany, Czech Republic, and Austria.

This area is mostly rural, and no estimates were given about the size of the affected population. In a worst-case scenario, the asteroid would inflict damage extending out for 150 km in all directions. A threat map indicated the regions designated as unsurvivable, critical, severe, and serious. Prague, a city of 1.27 million people, resides on the outer border of the serious zone, while Munich appeared to be out of harm’s way.

Had this situation been real, the International Asteroid Warning Network — a group that detects, tracks, and characterises potentially hazardous asteroids — would have disseminated this information in accordance with an UN General Assembly resolution, according to today’s report. This would be to done to “ensure that all countries … are aware of potential threats,” and to emphasise the need for developing “effective emergency response and disaster management in the event of a near-Earth object impact,” according to the resolution.

Stickle said several things stood out to her about this year’s exercise, including the importance of clear public communication, particularly providing information to people about the threat and what can be done to prevent impacts on Earth.

“I think DART can be a good addition to this as an example of how we are preparing and testing the needed technology; the mission provides a good opportunity to have public communication and engagement,” wrote Stickle. “The exercise also showed the importance of being able to rapidly deploy kinetic impactors in an emergency scenario.” That said, she described the six-month timeline as being “pretty sporty,” as they’d have to act really fast, even with a mitigation solution ready to go.

Mallory DeCoster, systems and mechanical engineer and DART investigation team member also chimed in, saying we “really need to find and track more asteroids,” adding that this isn’t surprising, “but this short-warning-time scenario definitely highlights the importance of this.”

And with that the roundtable was complete, as there was really nothing left to do but wait for the asteroid to strike. It’s all very morbid, but this year’s simulation proved to be worthwhile. Hopefully these exercises will continue to remain within the realm of fiction.