I’ve never liked bugs. I frequently have nightmares about swarms of insects. So naturally, I’ve been anxious about the Brood X cicadas re-emergence for months, concerned that they’ll ruin the experience of eating at outdoor restaurants or hanging out on my deck on weekend afternoons. I know the bugs are harmless, but that doesn’t mean I’m happy about them. The pandemic isn’t over yet, so the outdoors is still where I’m doing most of my socialising. And now these bugs were planning on showing up uninvited.

I felt pretty sheepish about these feelings when talking with Gene Kritzky, an internationally renowned periodical cicada expert at Mount St. Joseph University. Kritzky has dedicated his whole life to these mysterious creatures that emerge at regular intervals from the soil, make a ruckus, mate, and then disappear underground again for 17 years in Brood X’s case. And not just his professional life, either. When he and his wife bought their house in Cincinnati two years ago, he told me, they “made sure to carefully inspect” the trees on their property beforehand to ensure they’ll be hospitable to cicadas.

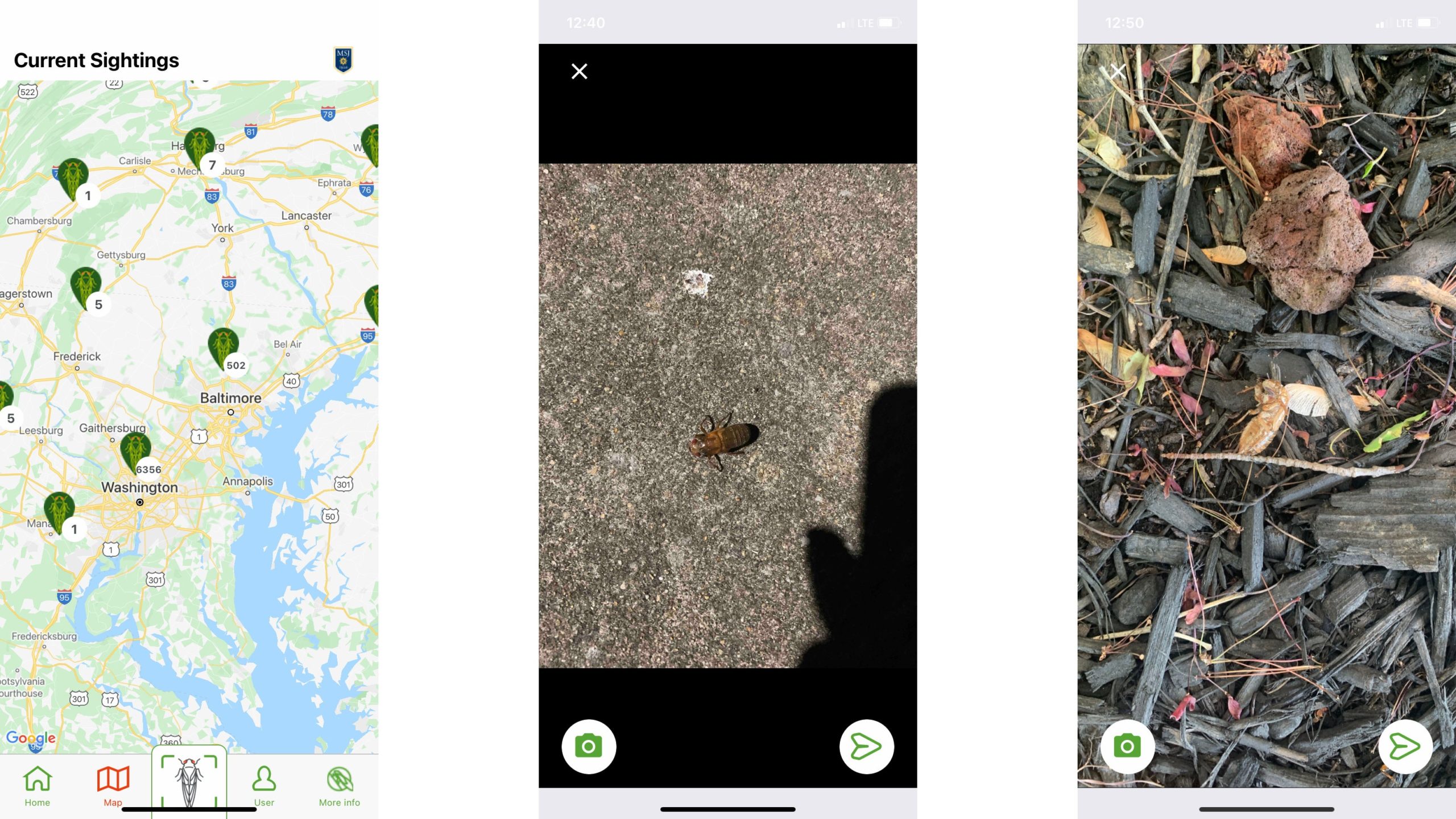

I called Kritzky to learn more about the app, Cicada Safari, he developed to track this year’s brood. It allows users to photograph the insects wherever they see them and document the bugs’ location by turning on GPS tracking. (Don’t worry, the scientists don’t “trace anything else you do like what you buy on Amazon or anything,” Kritzky said.) The pictures then get sent over to a team of researchers who look at each photograph to ensure that it does, indeed, show a cicada.

“I’ve got a couple dozen colleagues who are helping us look at every photograph with human eyes,” Kritsky said.

Approved photos go onto a live map that displays where each sighting has been. It’s updated in real time, so you can track the brood’s progress. When I first spoke with Kritzky two weeks ago, there had been just more than 150 documented sightings in Baltimore where I live, and nearly all of them were young nymphs, still in their shells. Today, the map shows more than 500, including many cicadas that are fully grown.

Citizen science has played a key role in scientists’ understanding of cicadas for decades. “Back in 1902, the Department of Agriculture sent out 15,000 postcards to people asking for information about the cicadas they were seeing,” said Kritzky. “They got just shy of 1,000 responses, and that was a pretty good rate!”

Technology has made researchers’ jobs a lot easier in 2021. Today, Cicada Safari has been downloaded by over 140,500 users who have collectively snapped 140,000 photos of the bugs and counting.

If you’re not Gene Kritzky, tracking broods may not seem that interesting in its own right. But what the cicadas are up to can tell us a lot about what’s going on in our backyards. For instance, the last time the 17-year cicadas came out in 2004, they were absent from parts of Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey where they’d previously been seen. Their emergence was also much patchier across Ohio and Indiana. Cicadas rely on tree roots to get most of their nutrients for the 17 years they spend underground, and the findings raised concerns about the effects of overdevelopment.

“Land use and deforestation are a big issue,” said Kritzky, who tracked both the 1987 and 2004 broods and saw sharp declines. “If you cut down a lot of trees for development, it can kill young cicadas that are deep under the ground.”

Hearing all this and downloading the app made me determined to get excited about the cicadas — or at least to learn to tolerate them. I don’t like the look of their beady red eyes or their giant waxy wings, but I wasn’t going to let that get in the way of ecological research. So I promised I’d force myself to look at the bugs for long enough to take a picture in the app. You know, for science.

Yet after steeling myself to stare a cicada right in the eyes, the bugs didn’t show up. They were expected weeks ago, but ground temperatures were too low for them to emerge. Despite my disdain, I started to worry about them. I didn’t want the unpredictable weather so common to our climate-changed world to screw them over. But the news reports said they’d be fine, and sure enough, it’s been getting warmer so the bugs are coming out.

I see cicadas everywhere now, and my forced acclimatization based on Cicada Safari is sort of working. I’ve been snapping photos of these guys left and right, and though I still find them spooky, they’re not keeping me up at night. The cicadas’ song is also now downright soothing. And I’ve been fondly remembering how the last time they emerged when I was 11, I’d pick their shells off trees with my grandmother and watch in horror as my middle school classmates dared each other to eat the bugs raw.

This week, some friends and I watched a cicada moult from its shell for a solid five minutes on my parents’ front steps in the suburbs. I was grossed out, but somehow also found it strangely endearing as the bug entered the world anew.

“I mean, this is certainly better than the other plague we just went through,” I joked.

“Yeah, and I mean, so relatable that it’s coming out from its comfy clothes after a long lockdown period. My shell was sweatpants,” my friend replied. Cicadas: they’re just like us.

Kritzky described cicadas’ emergence as “beautiful.”

“You can watch them leave their shells and slowly transforming into adults in front of you,” he said. “It’s amazing to watch with kids, especially. It’s like having a David Attenborough movie in your backyard.”

Though I wouldn’t go that far, I have been thinking about how cool it would be to see this phenomenon with children. I don’t have any now, but maybe I will the next time Brood X emerges in 2038.

No one knows, though, what that brood will look like. A lot can happen in 17 years. As one scientist told the New York Times, an area of Long Island where the insects once thrived is now a Walmart parking lot. The 17-year slumber for some members of Brood X born this year could become permanent.

The climate crisis can throw the cicadas for a loop, too. Scientists suspect that the increasingly unpredictable weather could be messing with some of their rhythms. Different species of cicadas emerge on different time cycles — some crawl up annually, some every five years, some every 13 years, some every 17. Kritzky said that in recent broods of all these species, many cicadas have been emerging early.

“Cicadas monitor the passage of time through the monitoring the fluid flow in the tissue of trees,” he said. “And so if, for example, you have a warm winter and the trees start budding early, but then there’s frost and all those buds drop, then some cicadas will count that as two years instead of just one, so they’ll miscalculate when to come up.”

The time between now and when Brood X next emerges will be absolutely crucial for the future of the planet. Climate scientists have made it clear we need to zero out our greenhouse gas pollution by 2050 to keep the absolute worst impacts of climate change in check. By 2037, we should at the very least be well on our way to that goal. If we fail, swaths of the world will no longer be hospitable to many creatures, including human beings. I’ve made my uneasy peace with cicadas this year. And though we may never be best friends, I hope our ecosystems can still sustain them the next time they emerge so that we can meet again.