Over 174 million years ago, a squid-like creature was chowing down on an ancient crustacean, only to find itself scooped up as a meal by a prehistoric shark. Three creatures left their mark in time in an extraordinarily well-preserved fossil in Germany.

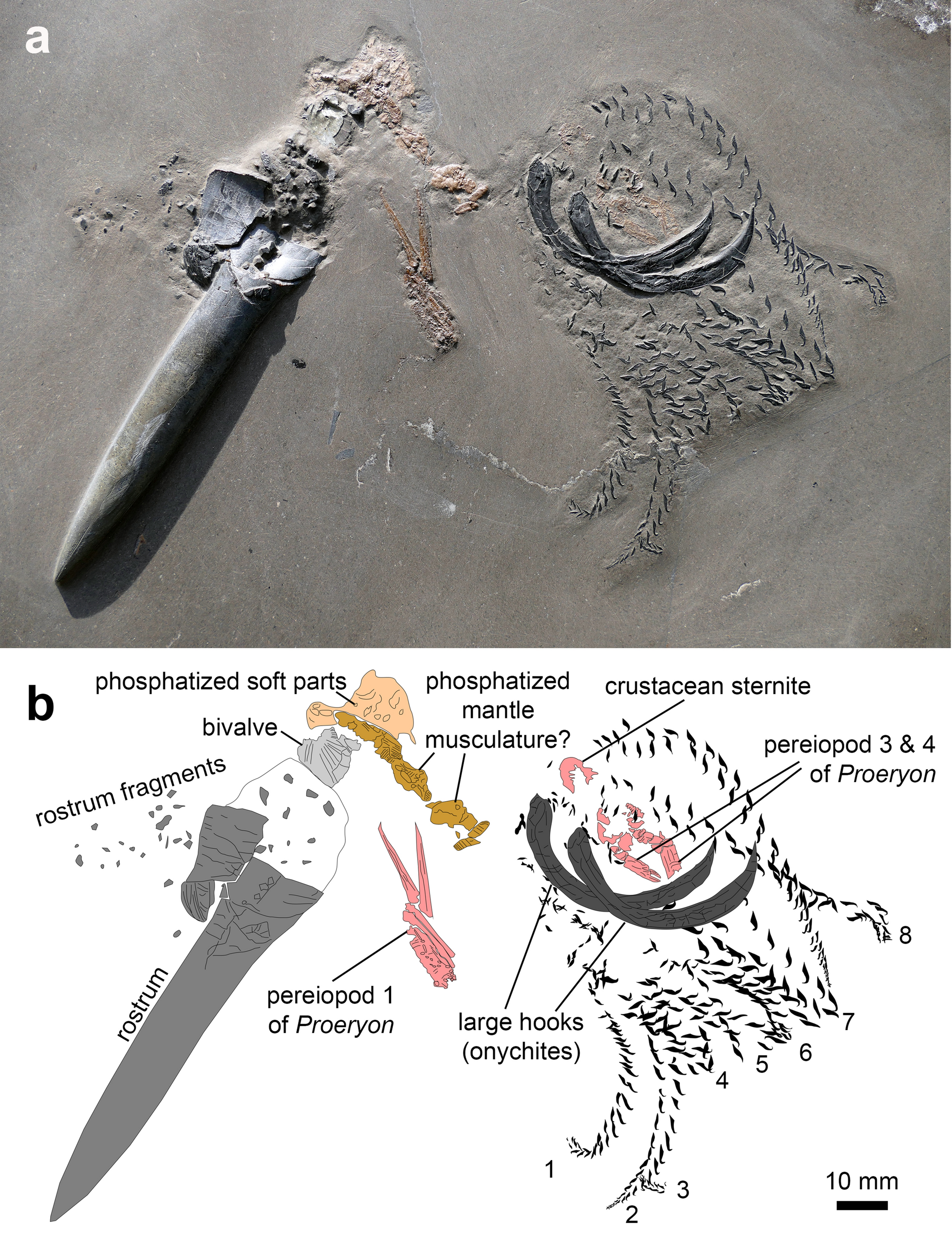

This particular food chain required a bit of detective work. Immediately recognisable in the fossil itself are the hard parts of a belemnite, a type of sea creature resembling today’s squids: hundreds of little hooks, two large hooks, and a torpedo-shaped shell called a rostrum. Bits of fossilised soft parts of the belemnite extend from the shell, and the claws of the crustacean are interspersed within the hooks. The shark, however, is completely absent. There are no bite marks. And yet, the authors of a paper published this April in the Swiss Journal of Palaeontology say that this fossil is in fact the remnant of a meal from a large marine predator. In other words, what remains for us today is what that shark Hybodus spit out.

It’s not an outlandish leap to suggest this. Also in the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart (SMNS), which houses this fossil, is another exquisitely preserved specimen of one such shark from the same time period. And within its ancient stomach are an estimated 200 shells of belemnites. This particular shark didn’t expel the hard parts, an act that might have led to its death.

Belemnites have also been found in the fossilised stomachs of other sea creatures, such as other large fish, ichthyosaurs, and marine crocodiles. Similarly, parts of ancient crustaceans have been found in association with belemnites.

Interpreting this fossil wasn’t a simple task. Lead author and curator of the Paleontological Institute and Museum at Zurich University Christian Klug explained in an email, “I first thought there were two crustaceans and that they perhaps scavenged on the belemnite carcass. But then it turned out that all the pieces belonged to one crustacean. The mode of preservation then led to the conclusion that it is a moult. It is known from several cephalopods that they love eating molts (for reasons us humans won’t understand). Hence it was quite likely that the belemnite was nibbling on the empty shell.”

Adiël Klompmaker, curator of paleontology at the Alabama Museum of Natural History, University of Alabama, said that soft-tissue preservation is “tricky” and remarkably rare. Thus, “for this research,” he wrote, “one may argue that the softest parts of the belemnite simply decayed prior to fossilisation without needing the predation event by a large vertebrate as an explanation. However, the rostrum and arms are not aligned, but are oriented at an unnatural right angle. Moreover, some soft tissue such as muscles of the belemnite are actually preserved, yet much of the rest of the soft tissue is missing. Both points argue against preservation as an explanation and favour the predation idea.”

He questions, however, whether the crustacean was a moult or “leftovers of a corpse.”

“The more edible, less calcified parts of the crustacean, which may have been targeted by the belemnite, are gone,” he said. “If correct, the belemnite actually may have caught a living (or recently dead) crustacean on or near the ocean bottom, did not pay close attention to its surroundings as a result, and subsequently got caught by a large vertebrate predator. It probably happened close to the ocean bottom, because that is where the lobster lived and the fact that both ends of the belemnite, the rostrum and the arms, are preserved very close to each other, which would be less likely had it happened high in the water column. Thus, the slab with the fossils may represent a double act of predation, which is so rare! The vertebrate predator may have intentionally left the rest of the belemnite because it is less edible or the predator got distracted itself.”

Allison Bronson, a paleoichthyologist — someone who studies ancient fish — at Humboldt State University, agrees with the conclusions made by these authors. “Sharks are intelligent animals,” she wrote in an email, “and just like a living shark might mouth something to figure out if it’s edible, this fossil shark probably decided the soft bits of the belemnite were good, but this large, hard rostrum wasn’t worth ingesting.”

She offered examples we see today, such as “sleeper sharks trying to eat a hagfish, getting their gills clogged with hagfish slime, and then spitting the hagfish out; an angel shark trying to eat a horn shark, getting poked by the horn shark’s dorsal spines, and then spitting the still-living horn shark out.”

The remnants of a meal are considered traces — something that is left behind. So, although there are body fossils of the belemnite and a crustacean, the overall fossil is considered a trace fossil: partially eaten food that is dropped. The authors propose the new term ‘pabulite,’ from the Latin ‘pabulum’ (food) and the Greek ‘lithos’ (stone), or ‘leftover meal’ as a way to describe these types of ichnofossil. They explain that there are many pabulites in the fossil record, but to date, few are described in papers or displayed in museums.

“What’s remarkable about this, to me, is that it’s fossil evidence of a decision,” Bronson said. “Whether this was a large shark or a bony fish that tried to eat this Passaloteuthis (we can’t know without some fossil teeth or evidence of bite marks, really) that animal made a decision not to continue ingesting the prey item.”

Jeanne Timmons (@mostlymammoths) is a freelance writer based in New Hampshire who blogs about paleontology and archaeology at mostlymammoths.wordpress.com.