In the grand pantheon of DC Comics characters with decidedly uninspired names (see: Superman, Batman), the Japanese assassin-turned-antihero Katana — codename of Tatsu Yamashiro — has always stood out as being a prime example of how comics have a long history of conceptualizing heroes and villains of colour in rather reductive ways. The latest issue of John Ridley’s The Other History of the DC Universe sets to put right some of the disservice that’s been done to Tatsu over the years.

Katana has been a member of teams like the Outsiders and the Suicide Squad where both her sharp mind and skill with a supposedly mystical sword made her a force to be reckoned with. Like all of The Other History of DC’s character studies, the series’ third issue traces the broad arcs of her life in DC’s comics in order to revisit familiar moments from her history. It’s done with a perspective that’s more honest and cognisant of how her being a Japanese woman has shaped the trajectory of her life.

[referenced id=”1522581″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/10/the-other-history-of-the-dc-universes-john-ridley-on-giving-new-voices-to-legacy-characters/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/26/other-history-dc-300×174.png” title=”The Other History of the DC Universe’s John Ridley on Giving New Voices to Legacy Characters” excerpt=”DC Comics’ long-awaited The Other History of the DC Universe from Oscar-winning writer John Ridley is set to debut next month. Gizmodo spoke with Ridley recently about what it’s been like figuring out how to give fresh voices to an expansive cast characters who, while well-known in certain circles, have…”]

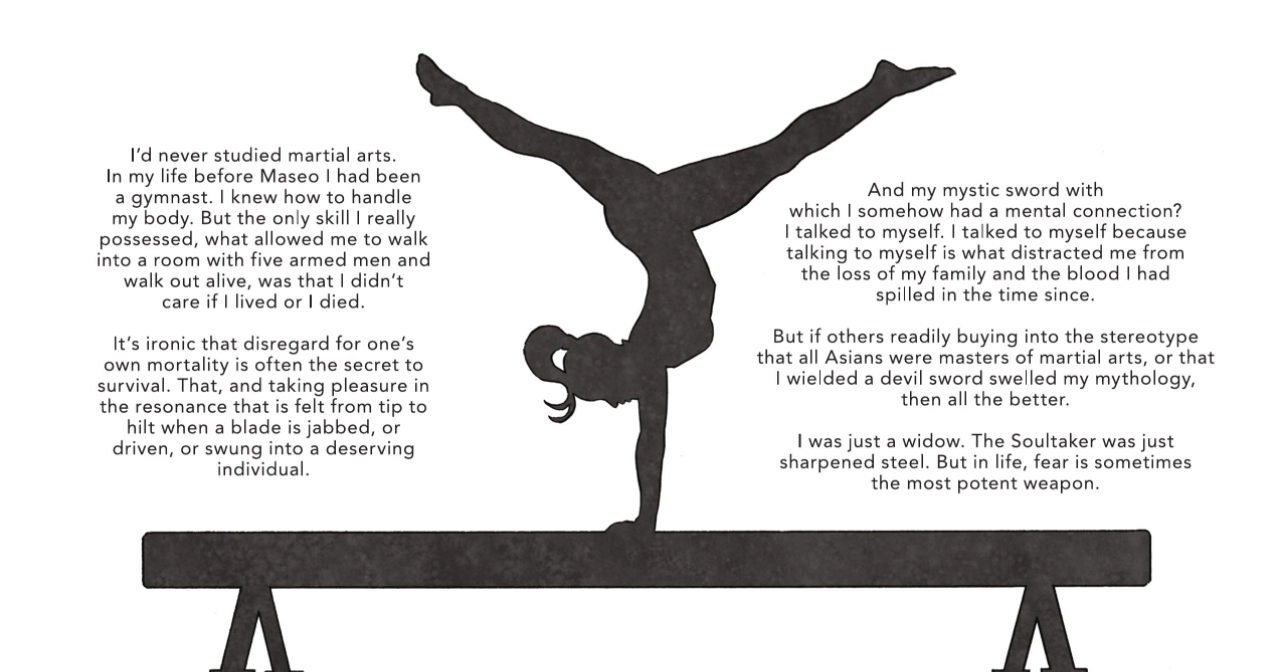

The Other History of the DC Universe #3 opens with what amounts to a direct acknowledgment of the reality that within Katana as a character, there are a number of generalized ideas about Asian identity and Asian women specifically that — while thought of as progressive by their creators back in the ‘80s — often amounted to stereotypes worth unpacking. As is the case with many comics characters, her origins tie back to a traumatic moment in her past — specifically the night her yakuza brother-in-law Takeo beheaded her husband (his own brother), and then forced her to watch as he set her house on fire with her twin sons trapped inside. Driven by lust and disregard for Tatsu’s life, happiness, and will, he attempted to take all of those things away from her with a blade, but in doing so left Tatsu with a different sort of emptiness that would transform her into a lethal killer.

Ridley contrasts the abject loss of Tatsu’s family, a deeply personal experience, with the social stigma that she would carry as the sole survivor of the attack on her family. Questionable as Ridley’s lines like “I was bad fortune, and throughout Asia bad fortune is taken seriously” are, The Other History tries to situate Tatsu within a fictionalized Japan, where widespread misogyny would turn the tragedy of her family’s murders into a mark on her own character. It’s not guilt or honour that drives her to kill Takeo with his own blade, but the drive to survive, which is what kept her alive on the streets, and eventually brought her face to face with more yakuza, whom she made quick work of with her increasing combat skills.

The Other History establishes that more than an identity Tatsu took for herself, the Katana moniker is the product of people’s perceptions about who and what she is. Rather than developing any sense of who Tatsu was as a person, it was far easier for the people she encountered as she became a part of the criminal underworld to simply identify her by the weapon she carried, an explanation that works to a point in-universe, but doesn’t change the fact that character might as well have gone by Sword. Much as “Katana” was an attempt to place the whole of Tatsu as a person into an understandable box, she came to understand how she could use it, and people’s misconceptions about her skills and her sword’s abilities, to her advantage.

Depending on which continuity she’s set in, Katana’s Soultaker Sword can sometimes live up to its name and absorb the soul of the person it murders, giving the wielder a psychic connection to the entrapped spirits. Here, though, the legends that follow Soultaker are rooted in people’s assumptions that the tales about it and the legendary martial artist who carries it are all true. It’s not people of colour’s responsibility to reclaim the ridiculous stereotypes projected onto them by others, but in doing so The Other History’s Katana put herself in a position to leave a painful chapter of her life behind her. When settling elsewhere, as successful as she became working as a mercenary for her wealthy patron Tadashi, crossing paths with Batman ultimately put her on her path towards heroism.

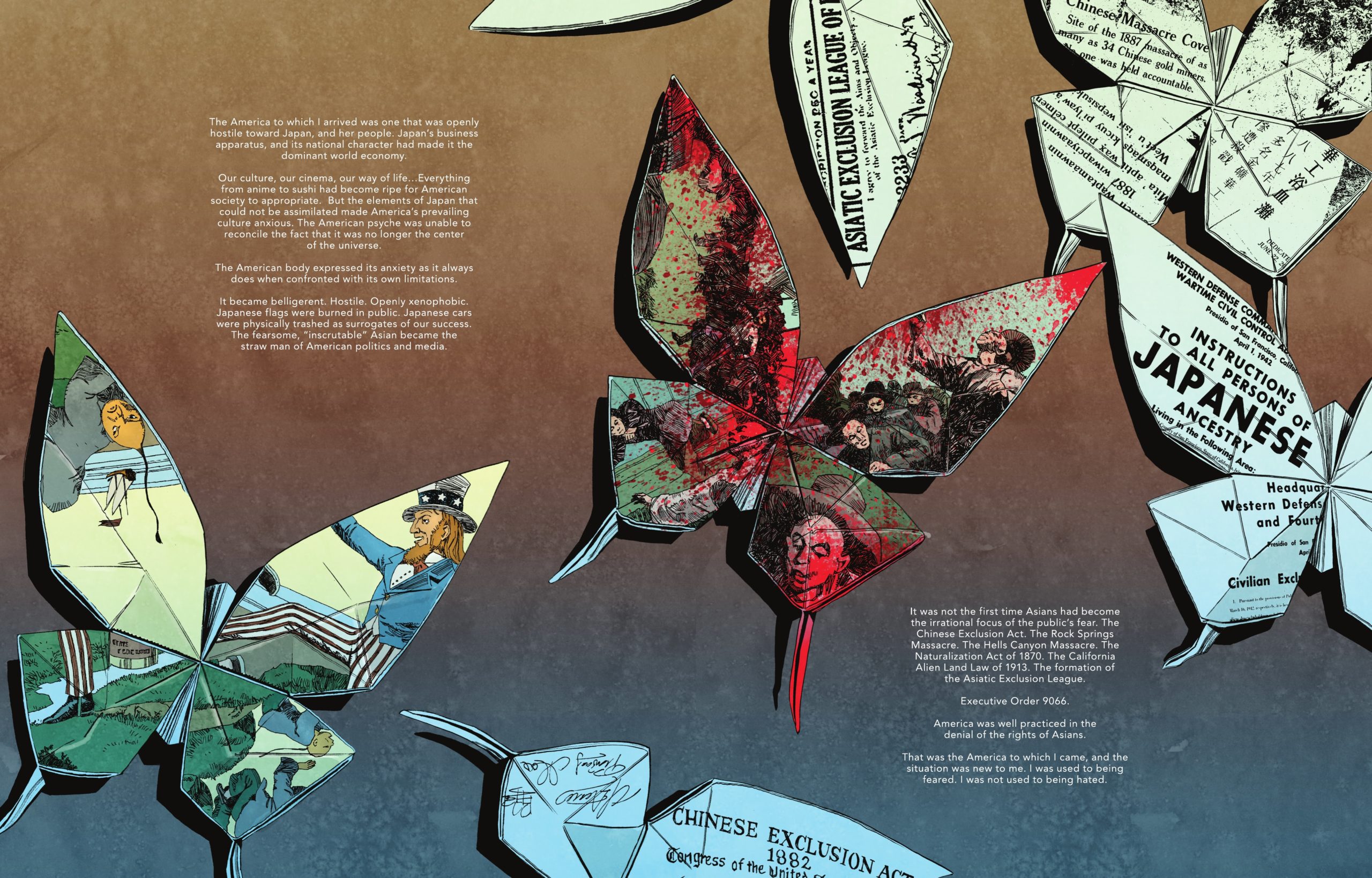

What really stands out about The Other History’s depiction of Katana’s journey West to work with the Outsiders is how becoming part of the group — initially a ragtag bunch of people who didn’t trust each other working under Batman — played an important role in framing Katana’s perspective on the overt anti-Asian and anti-Japanese racism she experienced in the United States. Rather than acting as a shield against racism for her, the Outsiders became a place where the intrinsic power she had merely by existing was recognised, valued, and encouraged, in part because it made her a stronger vigilante.

At the same time that Katana grows into the newest version of herself, The Other History zooms out to emphasise what sort of societal obstacles people of Asian descent face in DC’s fictionalized take on the U.S. that, here, draws direct inspiration from the real-world murder of Vincent Chin. In 1982, 27-year-old Vincent Chin, a Chinese American draftsman, was savagely beaten with a baseball bat by Ronald Ebens and his stepson Michael Nitz, two white men who attacked him following an earlier altercation that evening at a nightclub.

Chin’s attack and subsequent death days later was the ultimate result of decades’ worth of America’s generalized hostility and discrimination towards Asians as a whole that came to a particular, though not isolated, point in the Metro Detroit area in the ‘80s. At the time, the ascendance of the Japanese automotive industry was seen as a direct threat to American manufacturers and jobs held by white Americans, and multiple people present the night of the attack reported that Ebens directly expressed his belief that Chin was part of the problem. Chin, a Chinese American man, being the target of racial harassment intended for the Japanese is just one of the many ways that his murder illustrated part of the ugly, violent realities of what anti-Asian racism in America has looked like in the past, and continues to look like today.

[referenced id=”1033864″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2017/04/george-takei-partners-with-idw-for-comic-book-about-time-in-wwii-internment-camp/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/02/uzrdpesphh69c1ygyskn-300×169.jpg” title=”George Takei Partners With IDW For Comic Book About Time In WWII Internment Camp” excerpt=”George Takei’s recounts of his time at a Japanese-American internment camp have been put to page and brought to the stage. Now, he’s signed a book detail with IDW Publishing to create a graphic novel about what it was like for those imprisoned because of their heritage.”]

Months after Ridley presumably wrote the script for The Other History of the DC Universe’s third issue, but just two weeks before the comic’s release, eight people, six of whom were Asian women, were murdered in an Atlanta mass shooting. A 21-year-old-white man, who was ultimately taken into custody by police, is thought to have sought out a place where Asian people were likely to be in order to commit his act of domesticated terrorism. The March 16 mass shooting was but one of many horrific data points within a larger story illustrating the rise of targeted attacks against people of Asian descent here in the U.S. — something almost undeniably influenced in part by the Trump administration’s repeated attempts to assign blame for the covid-19 pandemic.

Though the specific circumstances of Chin, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Soon Chung Park, Hyun Grant, and Suncha Kim’s deaths were different, they were all confronted with one of the most sickening forms of racism that the public is often all too ready to look away from for fear of what regarding it for what it really is would reveal about our society. By making Chin’s death a part of DC’s world, The Other History of the DC Universe #3 puts Katana in a position to consider what that means for her. As a Japanese woman who lives in America, but does not exactly lead what one would consider a typical life, Katana’s perspective on how racial animus manifests within the U.S. is nuanced and somewhat bigger picture in a way that’s admirable, but not always easy for real people to actually have.

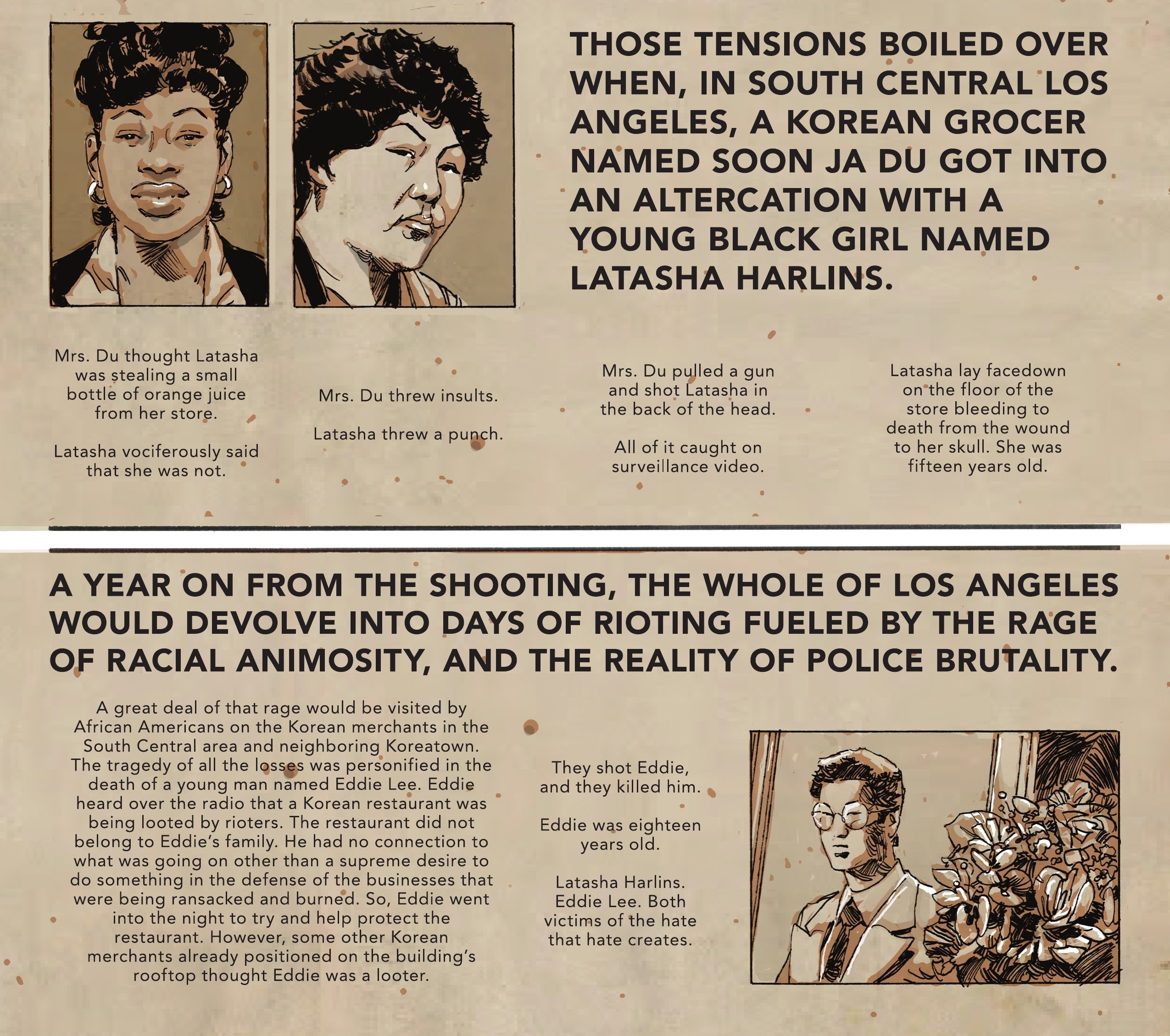

Ridley’s Katana understands that the tensions running deep between South Central Los Angeles’ Korean and Black communities in the ‘90s are precisely what led to Soon Ja Du, a 51-year-old liquor store owner, shooting and killing 15-year-old Latasha Harlins after accusing her of stealing orange juice. Katana grasps how Harlins’ murder further stoked the flames in people’s hearts that led to protests, demonstrations, and riots — all of which are expressions of rage at injustice — that in turn left innocent people on “both sides” hurt.

Running through all of this, though, is Katana’s keen perception that at the heart, both American minority groups’ grief and struggles are rooted in their respective experiences being subjugated by the larger power structures that have always taken advantage of people of colour and in many instances pit them against one another. The Other History isn’t prescient about the recent mass-shooting in Atlanta as much as it is a story trying to convey how tragedies like it are decidedly American events.

It’s not up to Katana to prevent these things from happening — because that’s not something that she alone could ever accomplish. Rather, The Other History ends wanting you to know that Katana has seen and taken to heart these events, not as things that constantly weigh her down and define the whole of her being, but as parts of reality she can’t ignore. Of all the kinds of lessons one can take away from comic books, “Look around and contextualize the real-time hatred that’s flowing through your world” is one of the more important ones, and The Other History of the DC Universe is one of the few out there trying to encourage people to do it more.

The Other History of the DC Universe #3 is in store now.