Rather than dole out what is, essentially — at least to one of the richest companies on the planet — a handful of spare change, Facebook set out to purposely undermine one of the most important legal protections Americans have against unwanted robocalls. Today it accomplished that mission.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday issued an opinion that negates decades of work by Congress to shield Americans from the plague of automated phone calls. Specifically, the court chose to accept a narrow view of what constitutes an “autodialer,” also known as an automatic telephone dialling system (ATDS), under the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA). The court’s interpretation effectively limits that definition to only systems that target sequentially or randomly dialed numbers.

Under this definition, companies are free to employ automated dialling systems that target thousands or even millions of consumers, so long as the database of numbers they use isn’t pulled from thin air. Of course, the odds of most companies getting caught breaking that rule is infinitesimal, and the financial benefits of violating the law may outweigh the risk of liability involved.

“Companies will use autodialers that are not covered by the Supreme Court’s narrow definition to flood our mobile phones with even more unwanted robocalls and automated texts,” Margot Saunders, senior counsel for the National Consumer Law Centre, said in a statement.

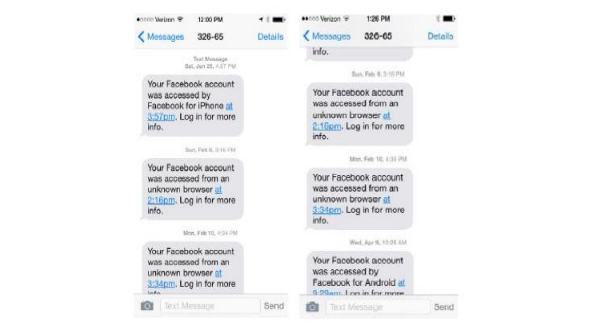

The court’s decision comes as a result of a rather petty effort by Facebook to avoid paying off an individual whom the company had bombarded with unwanted texts. In 2015, a man named Noah Duguid sued Facebook saying he’d received numerous text messages alerting him that his Facebook account was being accessed from an unknown device. The problem was, Duguid didn’t have a Facebook account. He had never created one.

While the texts were a nuisance, Duguid didn’t simply run to the court to solve his problem. He attempted to follow instructions that Facebook provided. And even though Facebook notified him the problem was solved, it wasn’t. The texts kept coming. Duguid went back to Facebook again and again, asking the company to stop with the texts. But Facebook only sent back automated replies telling him to modify the settings of his nonexistent account.

A “human needs to read this email and take action,” he wrote in one final message. Facebook responded with the same automated reply.

Fed up, Duguid finally contacted a lawyer and filed a lawsuit against Facebook in California, asserting the company had violated the consumer protection statute. Rather than admit its error, address the problem, and pay Duguid a nominal fee for his inconvenience — $US1,500 ($1,973) per text — Facebook’s lawyers, having seemingly nothing better to do, decided to pursue the case all the way to the nation’s highest court.

The Supreme Court applied a strict textual interpretation of the TCPA, which was signed into law in 1991, long before the existence of modern autodialer technologies. While Duguid’s case was based around the idea that an autodialer is effectively a system that can be used to store phone numbers for the purpose of transmitting unsolicited and unwanted texts, the court found that definition was overly broad and would, in effect, include virtually every cellular device in existence.

Although the law may have been enacted in pursuit of “broad privacy-protection goals” aimed specifically at protecting consumers from intrusive telemarking practices, that “does not mean it adopted a broad autodialer definition,” the court said. “Congress expressly found that the use of random or sequential number generator technology caused unique problems for business, emergency, and cellular lines.”

The court also rejected the idea that its ruling would, as Duguid argued, “unleash” a “torrent of robocalls,” saying he “greatly overstates the effects of accepting Facebook’s interpretation.”

The opinion, authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, was joined by all members of the court, save Justice Samuel Alito, who filed a concurrent opinion — meaning he agrees with the outcome, but under different terms. (Alito takes issue with the way Sotomayor used a particular textual canon to inform her interpretation of what constitutes an “autodialer” under the TCPA, writing, “No reasonable reader interprets texts that way.”)

To be fair to Facebook, this is not the first time the courts have taken issue with modern interpretations of the statute. In 2015, the Federal Communications Commission passed a rule in an effort to crack down on robocalls. Similarly, the D.C. appeals court found that the agency had expanded the definition of “autodialer” so much so that one might interpret the rule as applying to anyone with a smartphone.

“It is undisputed that essentially any smartphone, with the addition of software, can gain the statutorily enumerated features of an autodialer and thus function as an ATDS,” the court said at the time.

“Americans already receive 46 billion robocalls a year,” said Saunders, whose organisation quickly called for a legislative remedy. They may get their wish.

In a joint statement, Rep. Anna G. Eshoo, a senior member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, and Sen. Ed Markey, who sits on the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee, denounced the decision, while calling for passage of a bill that would, in their words, “fix the Court’s error.”

“Today, the Supreme Court tossed aside years of precedent, clear legislative history, and essential consumer protection to issue a ruling that is disastrous for everyone who has a mobile phone in the United States,” they said. “It was clear when the TCPA was introduced that Congress wanted to ban dialling from a database. By narrowing the scope of the TCPA, the Court is allowing companies the ability to assault the public with a non-stop wave of unwanted calls and texts, around the clock.”