I’m not usually one to wax rhapsodic about an operating system, but let’s go back 20 years to just before the launch of Mac OS X and talk about what came before and everything that came after. Twenty years is a rare and important milestone for a piece of software. After all, most software rarely breaks the two-year mark let alone survives two decades. What made OS X special, way back when, and what is its legacy?

Mac OS X launched on March 24, 2001.

The 1990s were rough for Apple. Until 1997, when Steve Jobs took the helm again, the company attempted to right itself by creating a plethora of CE products — printers, PDAs, cameras — and allowing hardware clones to enter the market. The resulting confusion turned Apple into an also-ran and gave Microsoft’s Windows the dominant position. Windows was everything to everyone. Apple’s OSes — called System 7, OS 8, and OS 9 — were nothing to anyone.

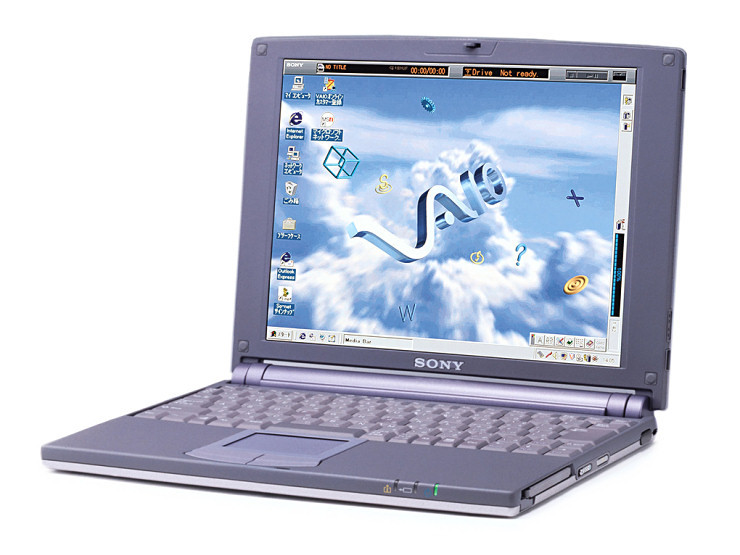

Meanwhile, tech was becoming cool. Sony and Gateway were telling two sides of the same story: buying their sleek and sometimes expensive Windows hardware was the way to win points at work and school. The internet wasn’t a thing you used, back then, and early devices looked like the immovable business hardware that they were. That changed in about 1997, as panic about Y2K came to a head. Everyone was buying new hardware to prepare for the inevitable crash and they didn’t want beige boxes. They wanted devices that looked like they belonged in the year 2000.

I remember an NYU professor musing on the magazine ads Sony used to take out that featured cyberpunks toting some of the slimmest Vaio laptops ever made to secret underground raves. Windows, for all its faults, got the job done, and everyone from the IT techs in some corporate fishbowl to the home computer enthusiast knew that it was the only game in town. Again, you didn’t go to coffee shops with your laptop. Instead, you went to computer clusters on campus or holed up in your room, tapping into a PC.

Most tech at the time was cool and usable, but Apple’s wasn’t. Sure, it worked, but it worked the way it worked in 1988. Software like Photoshop and Pagemaker ran beautifully on those old Macs, but not much else. Buying a Mac was a life choice akin to joining a fading cult. You wanted to believe, but everything pointed to your eventual disappointment.

You bought an Apple laptop if you wanted to stand out. They were expensive, clunky, and aimed at specific niches in the artist’s repertoire. You used a Mac if you were laying out a school newspaper or making early techno or editing wedding photos (even though most Windows machines were better suited for all of those). You bought a Mac with the understanding that your investment was in a small sliver of utility versus the galaxy of value afforded by Windows.

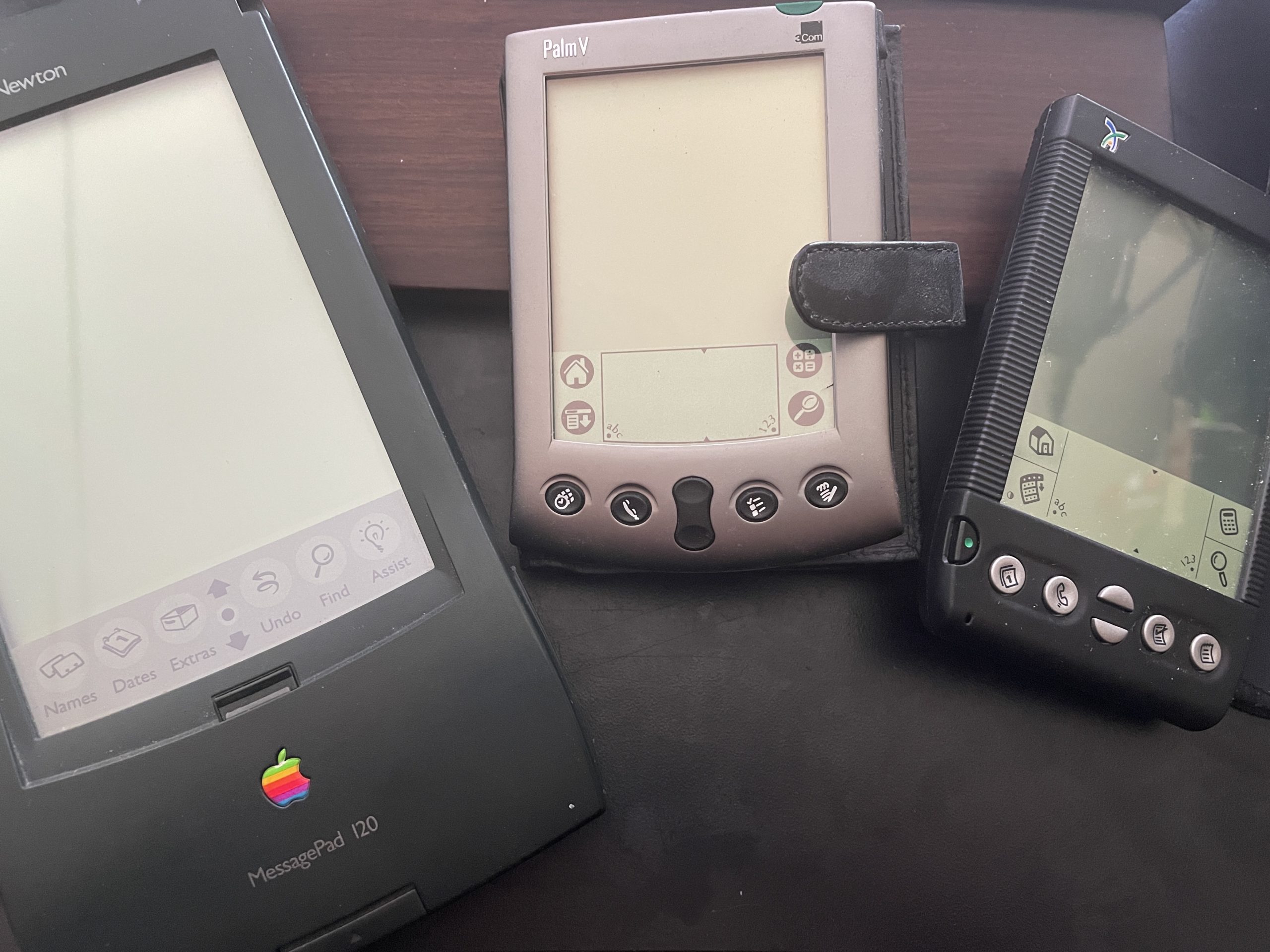

Take the Newton, for example. Released in 1993, it was supposed to define the PDA for the next decade. It was horrible. It worked like a price scanner in a grocery store, and the interface, all tiny text and icons, was unusable. It did a wonderful job at handwriting recognition, however, which put it ahead of its time. That said, it flopped. Instead, agile manufacturers like Palm and Handspring convinced scores of business analysts and Wall Streeters that they wanted something smaller and arguably worse.

Fast forward a few years, and things had changed. Entering the late 1990s was like walking into the Matrix. Tech was changing rapidly. Wireless connectivity and early mobile phone networks were jamming the airwaves. Apple, for its part, was changing too, implementing ideas from performance computing into a package that was as tantalising as a bag of candy.

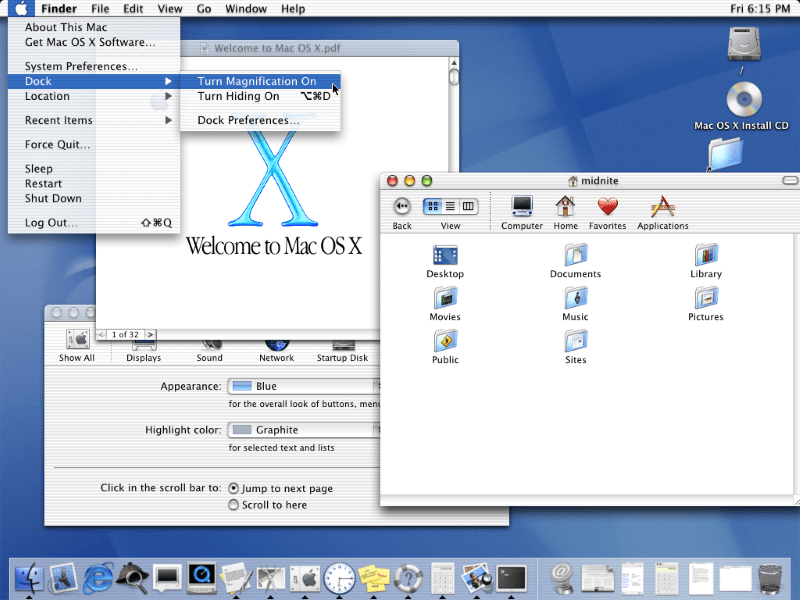

When OS X launched, it was a breath of fresh air. Although it went through a number of permutations (John Siracusa explores them all here) the final product offered an OS as new and exciting as the Bondi Blue iMac. In fact, it was the Aqua interface — bubbly buttons, transparency, plastic window bars — that defined Apple’s skeuomorphic tendencies for the next twenty years. In short, your OS looked like your computer.

It wasn’t an overnight success, but the iMac definitely put Apple on the map. My first official Mac, a 2005 Mac Mini, ran Tiger. Until that point, I cobbled together Windows machines out of scrounged parts. Now I had a lozenge of computing power that just worked. I was hooked.

Everything about this new OS was unique. The icons popped up like genies out of a bottle. The Terminal gave Unix hackers access to the guts of their powerful machines. Online users were quickly separating themselves from the offline sheeple and manifestoes like Neal Stephenson’s “In the Beginning was the Command Line” espoused a brave new future.

Microsoft limped along releasing XP and then Vista. It tried but failed to match Apple’s mix of aesthetics and cool. Once wifi became ubiquitous, you were far more likely to whip out a Macbook than a Thinkpad. Sure, let the cubicle-bound rubes use a Dell. With a Mac, you were riding an unstoppable wave.

When people say they revere Steve Jobs, this is what they’re talking about. They’re talking about a man and his team that redefined computing, making it cool, exciting, and fashionable. OS X was the vanguard of that frontal assault on the computing world, a charging force that made everyone realised that everything mattered, from keyboards to screens, to logos, to the very people seen using and loving your hardware. And it all started with OS X.

Windows is catching up. The new Surface devices are lovely, and Windows 10 is unique enough to be enticing. But there is something about Mac OS that keeps me coming back. Be it performance, power, or design, something of that Jobs magic still lingers in this 20-year-old code. One day we’ll figure out what it was and how to bottle it. Until then, we’ll just tap a single button on a stark and elegant machine and enter a world of computing dreamed up in the shadow of failure.