Imagine you’re a bank teller with a gun pointed at your head. What do you do? If you’re smart, you’ll just give the robber all the money he asks for. But if you’re an inventor from 1923 you’ve got a much better idea. You hit a button, causing an explosion that can be heard for miles and releasing a strong gas in the bank that knocks the robber unconscious.

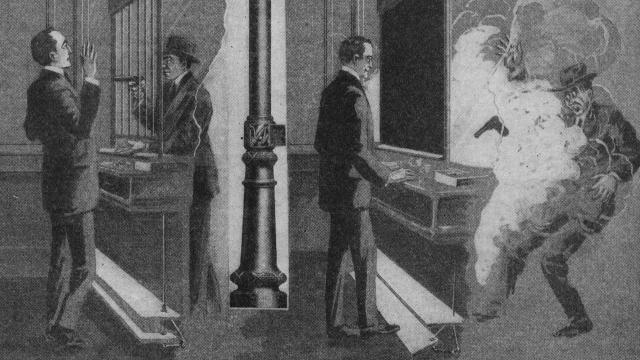

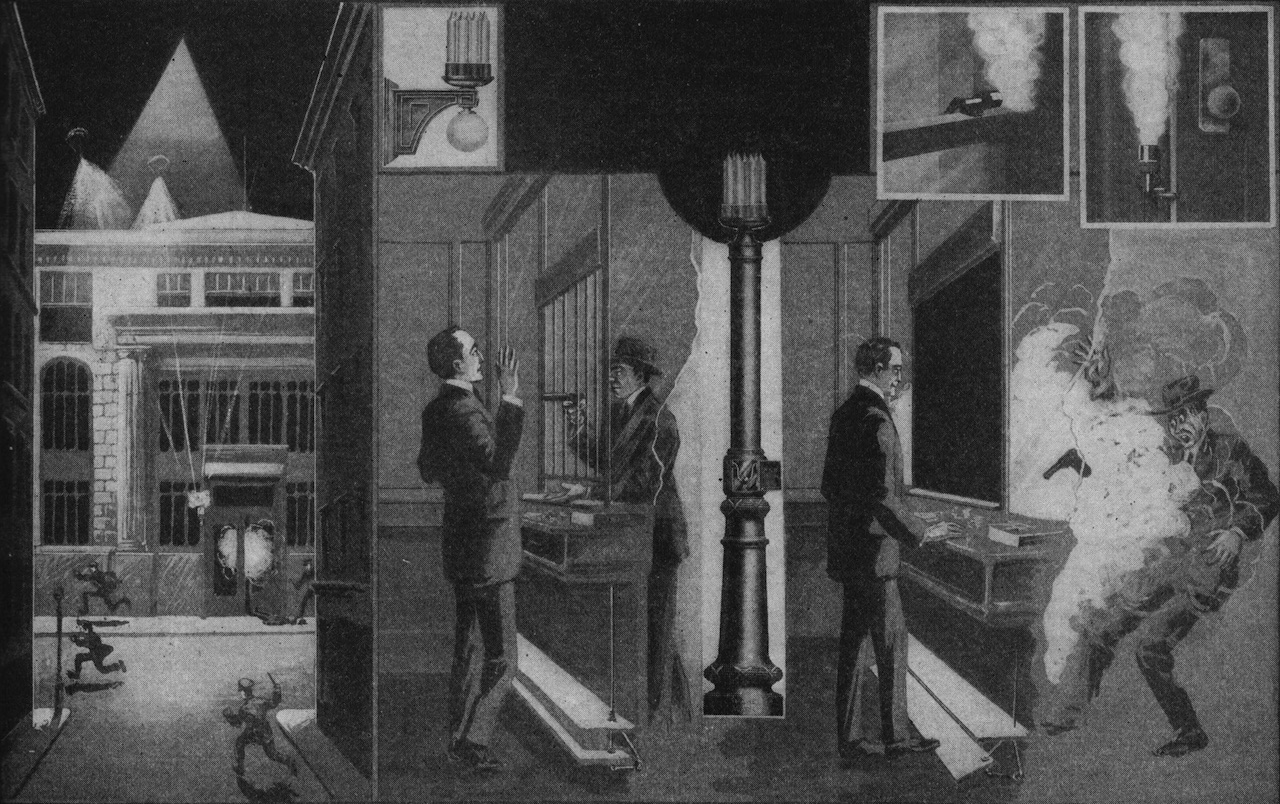

At least that was the idea behind an illustration that appeared in the April 1923 issue of Science and Invention magazine. The illustration was accompanied by an article titled “Gassing the Burglars” which explained the device, and included references to the horrific trench warfare of World War I, a conflict that was barely a few years in the rearview mirror.

The article in Science and Invention, credited to Eric A. Dime, stated that this invention was the work of Joseph Menchen Jr., an American who advised the British War Office during the early years of the first World War, before the U.S. would finally join the allies in 1917.

Menchen, who had developed a flamethrower for the British in 1915, had an idea that he called the Pyrotechnic-Aspyhxiation-Burglar Alarm, or P.A.B. Alarm for short, and Hugo Gernsback’s Science and Invention magazine seemed more than happy to promote it.

As Dime explained in the magazine:

Shocked, gassed, marked, deafened and possibly pinched, are the surprises in store for the thief who tries to run the gauntlet of the latest burglar alarm. This sounds as if the enemy of society found himself in a sort of “No Man’s Land” during wartime, while engaged in his precarious “trade” of breaking into buildings in quest of loot. As a matter of fact he does subject himself to some of the conditions of war, if he tries to rob a house that is protected with a P. A. B. Alarm. In other words this is the Pyrotechnic-Asphyxiating-Burglar Alarm, and it is a peace time application of some of the weapons of warfare employed by the armies in conflict during the late European struggle.

There’s a long history of wartime inventions making their way to productive peacetime use in the U.S., but the popular American imagination of the 21st century mostly thinks of these advances from World War II.

It’s rather jarring to see people of the 1920s talk about bringing home anything positive from World War I, let alone referring to the potential benefits of poison gas — especially when you remember that an estimated 500,000 troops were injured and roughly 30,000 died horrific deaths from chemical weapons during the first World War.

Nonetheless, Menchen seemed to think it was a wise use of these poisons to fill a bank with them so that they could incapacitate a potential robber. As the magazine explained, a device carrying a cartridge could be placed by a door and activated in a number of ways to create a loud banging sound that might be heard from up to five miles away.

The loud bang of the cartridge was intended to stun the robber’s ears but the thief was really supposed to be knocked out by the second feature of the device: a metal cylinder that could release gas.

From the magazine:

Forming a part of the alarm is a metal cylinder which contains a powder producing an incapacitating gas, and this gas is generated on the instant that the cartridge is discharged. The gas immediately fills the room, in which it remains like a heavy, yellow fog for about three hours.

Yikes.

The magazine goes on to insist that such a gas wouldn’t cause any “permanent injury” but it does “produce tears and a choking sensation.” The specific type of gas isn’t identified, but the gases used in World War I ranged from the less lethal tear gas to more lethal chemical weapons like chlorine and mustard gas.

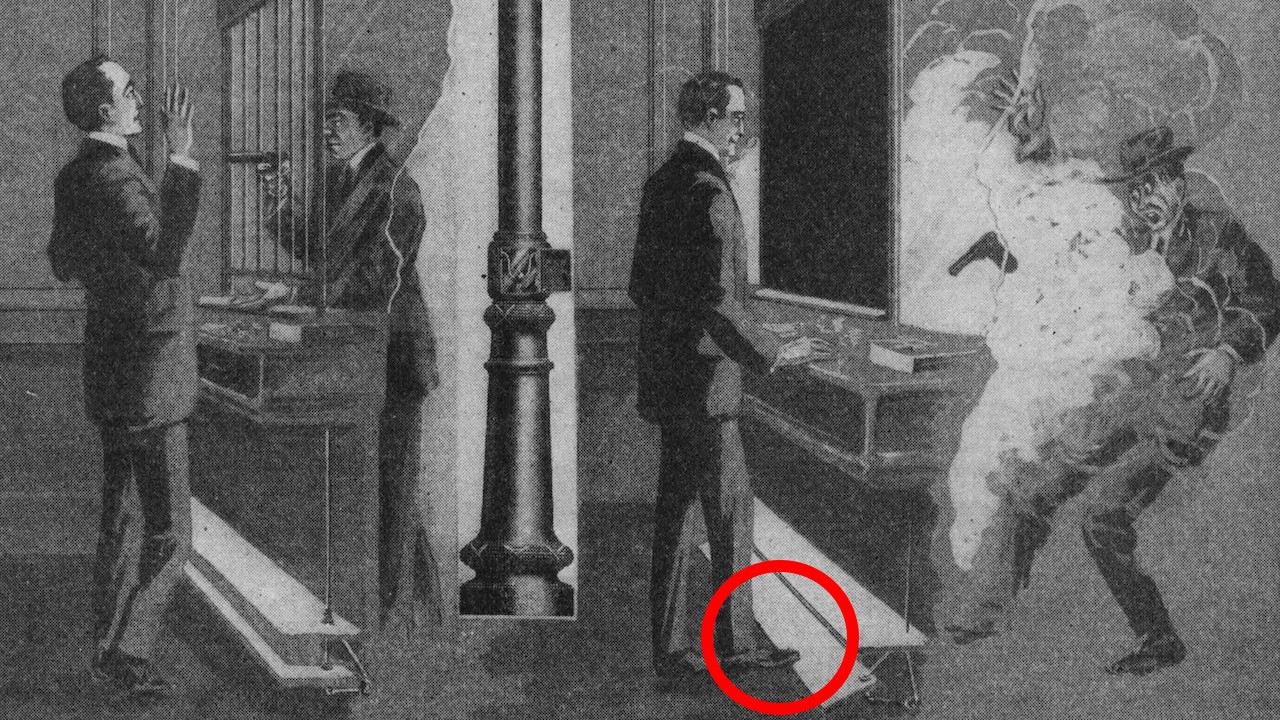

As you can see from the illustration, one possible way to deploy the unnamed gas would be to have the bank teller push a large plank down at his feet. What happens if the teller accidentally knocks the plank when he’s serving a customer rather than when he’s got a gun in his face? And how do you keep the gas from being inhaled by the teller? Those are just two of likely a dozen reasons I haven’t been able to find anyone who actually installed this invention in their bank back in the 1920s.

The article doesn’t specify how it could keep the bank teller safe, but there is a hint in the illustration that some kind of door would slide down to protect the bank teller from the poison gas. Could you do that quickly with a gun pointed at your head? Again, we wouldn’t bet our lives on it.

There were a number of different anti-crime devices of the 1920s that attempted to utilise battery and electrical technology that was developing relatively quickly after World War I. There was also the radio beacon of 1923 that was supposed to alert the authorities when you thought someone up to no good — an idea that utilised the burgeoning technologies of radio that would come to define the 1920s. There was the shock-watch of 1927 that was supposed to be something like a taser for your wrist, powered by a relatively enormous battery. And there was the very first breathalyzers, invented in the 1920s.

Wherever there are humans, there’s bound to be plenty of crime. And some of the technologies developed to fight criminal activity is more ethical than others. The first walk-through metal detectors weren’t even for keeping crime out of a sensitive area. The metal detectors invented to make sure that 1920s employees in Germany weren’t carrying metal parts home.

No one likes getting their property stolen, but there’s always a balance when anti-crime technologies are developed to incapacitate a robber. In this case, you didn’t even have to find much sympathy for the thief to realise a gas defence would probably be a bad idea for anyone.