What was the internet like in the 1970s? It was an incredibly small community of university researchers, government employees, military contractors, and more than a few spies. But those people all built and tinkered with the earliest technologies to create something that would transform the lives of everyone reading this message today.

One of the most vital technologies to emerge from this period was electronic mail or “network mail” as it was known at the time — something we call email today. And while we may think of email as integral to our experience of the internet, it wasn’t always a given. Email had to be invented, but once it was, people loved it.

Versions of electronic mail actually predate the internet, but they’re perhaps best thought of as electronic post-it notes because the message weren’t able to travel very far. A program called MAILBOX was developed for large time-sharing computers at MIT in the early 1960s to exchange messages between people who may have been just a few hundred feet apart. Time-sharing — the ability to utilise computers most efficiently by dividing up any downtime across a broad group of people — was one of the entire reasons computer networking and the ARPANET was so appealing. But even more importantly, the MAILBOX tool could be used to exchange messages between people who may be using the same computer at different times of the day or night.

The first host-to-host connection of the ARPANET, the precursor to the modern internet, occurred on October 29, 1969 between a computer at UCLA and a computer at Stanford Research Institute. And not even three years later, in 1972, proper email that was able to traverse the internet was invented by Ray Tomlinson, a government contractor at BBN. Tomlinson is the one who came up with the idea to use the @ symbol in email. Others at BBN, MIT, and ARPA, built on top of the work that Tomlinson did to improve electronic mail.

Back in 2015, I spoke with Stephen Lukasik, the former deputy of ARPA in the late 1960s and early 1970s (now known as DARPA) and he explained how he commissioned a study from MITRE to see how people were using the Arpanet. Astonishingly, roughly 75% of all net packets in 1974 were being used for email. Needless to say, email was a huge hit from the very beginning.

Email is an incredibly ephemeral medium for archivists, but thankfully we have some printouts from this period that gives us a sense of what email was like back in the 1970s.

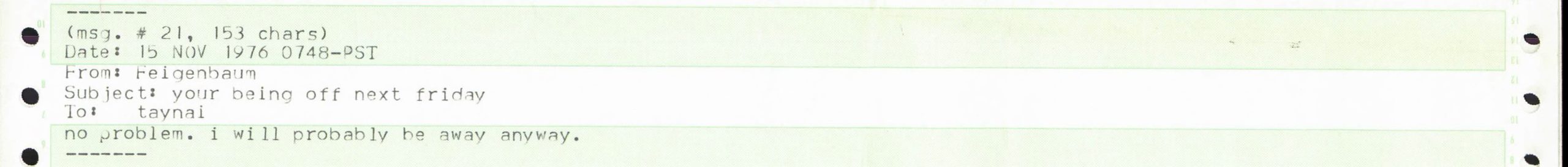

The messages from the 1970s would be familiar to anyone who uses email today, except for a few tiny tweaks. The messages are numbered, and it includes the number of characters in the message, like this email sent on November 15, 1976 to Edward A. Feigenbaum, who worked on artificial intelligence and computer science at Stanford University.

The messages of the early days could be short, as the one above. But they were supposed to be for official business. In fact, when UCLA’s Len Kleinrock sent a message of a personal nature in September of 1973 he felt like he was getting away with something illicit.

The legendary 1996 book Where Wizards Stay Up Late by Katie Hafner tells the story of Kleinrock returning from Europe to Los Angeles in 1973 only to realise he’d forgotten his electric razor at a conference. Kleinrock sent a message to Larry Roberts, another early internet pioneer like Kleinrock, and was able to get his razor back after Roberts alerted a mutual friend who was travelling back from the UK to L.A.

From Where Wizards Stay Up Late:

Kleinrock’s razor retrieval caper wasn’t the first time anyone had pushed past official parameters in using the network. People were sending more and more personal messages. Rumour had it that even a dope deal or two had been made over some of the IMPs in Northern California. Still, tapping into the ARPANET to fetch a shaver across international lines was a bit like being a stowaway on an aircraft carrier. The ARPANET was an official federal research facility, after all, and not something to be toyed with. Kleinrock had the feeling that the stunt he’d pulled was slightly out of bounds. “It was a thrill. I felt I was stretching the Net.”

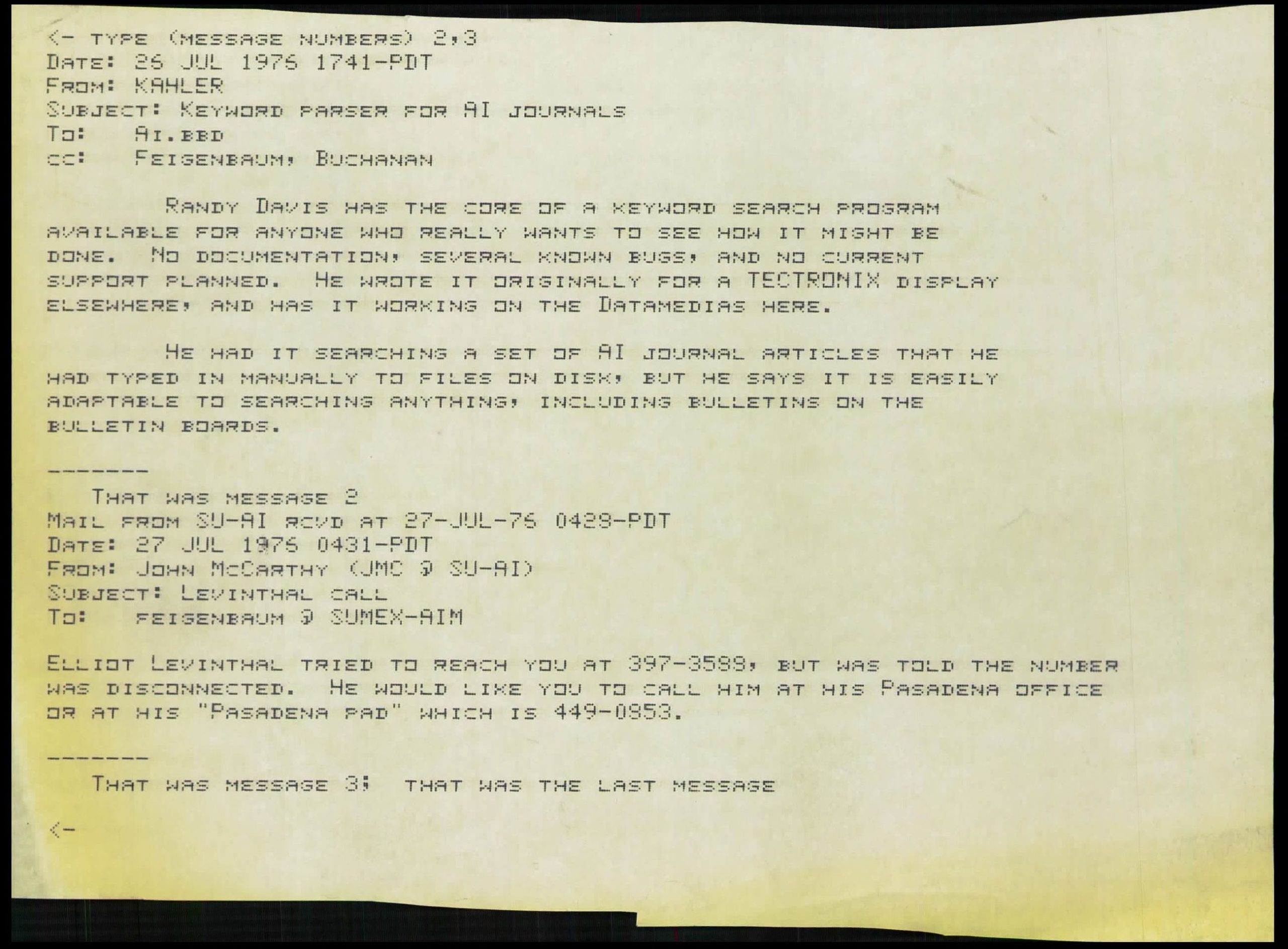

As can be expected, many of the discussions happening over email in the 1970s were over technical problems that researchers on the early internet were encountering. People would schedule meetings, discuss the problems, and brainstorm which tools might be best to tackle any given issues.

Below, we have emails from July 1976 that were printed out discussing a keyword program that sounds like it had plenty of problems.

The internet today is awash in all kinds of messages, including emails that flood our inboxes. The idea of “inbox zero” is a constant struggle for some people as we wake up in the film Groundhog Day to answer email after email.

People of the 1970s didn’t have fancy filters to automatically sort their email or make life “easier” through the wonders of automation. But there’s always an upside to the simplicity of any technology’s earliest days. In the case of email, it did seem like people valued this new communications tool in a way that no one wanted to waste it.

Yes, getting your electric razor back after forgetting it might not be a matter of national security. But such a task is obviously much more important than probably dozens of emails you’ve already received today.

How many of those emails are just invitations to Zoom meetings that could have been an email? They didn’t really have that problem back in the 1970s. At least most people didn’t.