While playing through Supergiant Games’ Hades I kept asking myself, why is this game so freaking good?

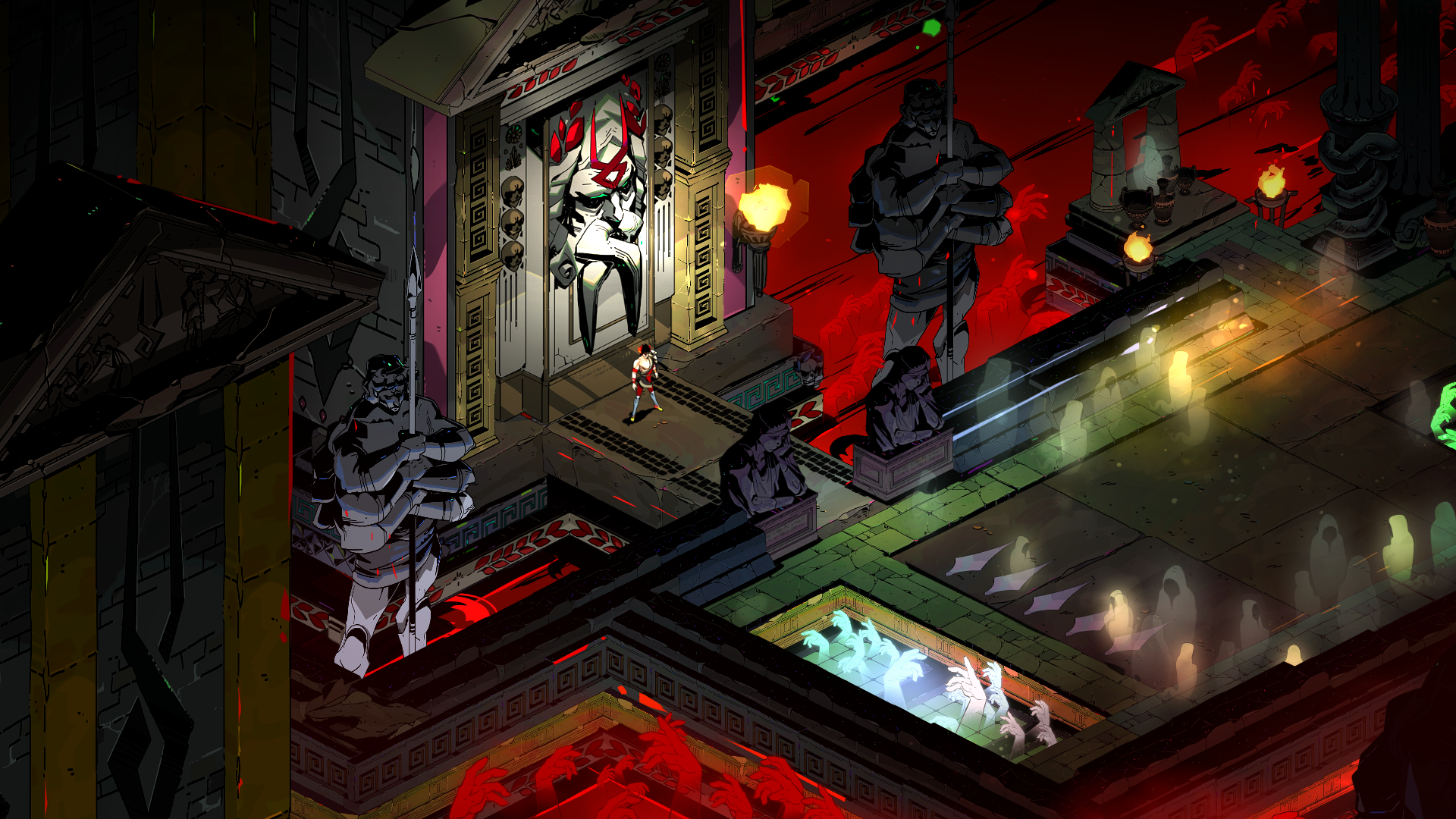

Sure, it’s just a flat-out fun game. You play Zagreus, son of Hades (that Hades, but not that Hades), an immortal prince of the underworld with mythical weapons who hastily kicks the crap out of demons on his way out of Hell. There’s also tons of strategy along with the carnage, and plenty of variety, too. Then, I died, and it all became clear.

Hades came out months ago (available on Mac, PC, and Nintendo Switch), and many sites named it the best game of 2020, or at least one of them. So I wasn’t making some major discovery when I downloaded it for my Switch. I was way behind the times and, admittedly, I may still be with this entire blog. It’s just that games are something I do mostly for fun, rarely for work, so I often am behind the curve on these.

When I started playing Hades I didn’t even know what the heck I was getting into. Everyone said it was a cool, addictive video game, so I bought it and began playing. Then I died, went back to the beginning, and realised this game was basically Groundhog Day in Hell. You try to escape Hell, you fail, you go back to the beginning and try again. Each time you gain experience — not mechanically, but experience in the kinds of threats you face on your way out of the underworld, from environmental threats to the boss characters that guard each level — or powers, literally boons from the Olympian gods, and then you try to do it again. And again. And again. Each time you get a little bit further, learn more, and eventually, hypothetically, get all the way to the end.

I’m not there yet. In fact, I’m still pretty early on in the game. But even early on I realised Hades is so good because it’s an incredibly fun, smart microcosm for life itself. Think about it. Every day we wake up, we go through the motions, learn something, lose something, gain something, go to sleep, wake up again, and repeat the same pattern. Every day we get a bit older, a bit wiser, and eventually — hopefully later rather than sooner — we “escape.” Zagreus’ quest to find meaning for himself and his relationship with his titular father in Hades is just the process of life itself, albeit in a fictional skin.

Now, the mechanics of Hades aren’t anything new. It’s part of a genre called Rougelite — itself a permutation of the more hardcore Roguelike genre — where, instead of a single, linear, pre-designed story or series of levels, you go on “runs” through randomly-generated pathways and encounters, starting the cycle anew if you fail at any point along the way, be it five minutes in or at the final boss. However, Hades is unique in how it deepens and engages with the mechanics of the genre.

Unlike most Rogue-style games, resetting (aka dying) is a crucial part of the story. You are required to die to progress the story. Every time Zagreus falls in battle, he wakes up out of the river Styx back at the house of Hades ready to attempt escape and defy his father once more. Each time he does, there are characters to talk to, new story beats to chase — death isn’t the “end” of a run, but the next step into a new chapter. The game slowly reveals more story, more weapons, more chances to move further and level up more. You have to grow up to move on.

Which, again, isn’t a groundbreaking concept. Most great video games tell a story — linearly, or around the stories we tell about their mechanics. A lot of great games also require you to level up. But those games also, mostly, have a forward momentum. Sometimes you go back a bit but repeating the entire game over and over, while also levelling up, takes Hades to the next level. It’s a video game that mirrors that weird banality of life in ways most other games can’t.

Now, what does it teach us about life? That’s a different story entirely, and one I’m guessing I’ll have to finish the story to truly figure out. Quite literally, I’ll be dying to try.