As the famous X-Files poster declares, “I want to believe.” This wanting, however, often leads us astray. When confronted with shocking and inexplicable celestial phenomena, we tend to see intelligent design. This jumping to conclusions is a sin for which we can be forgiven — we have an insatiable need to know if someone’s out there. When we say, “I want to believe,” what we’re actually saying is, “I hope we’re not alone.”

From the moment the first members of our species took the time to look up and ponder existence, we’ve been misinterpreting the stars. Someone once told me that ancient peoples probably mistook the tiny twinkling dots above for distant campfires, in what was probably the first example of humans “seeing” aliens that aren’t actually there. We’re still doing this, as these historical examples demonstrate.

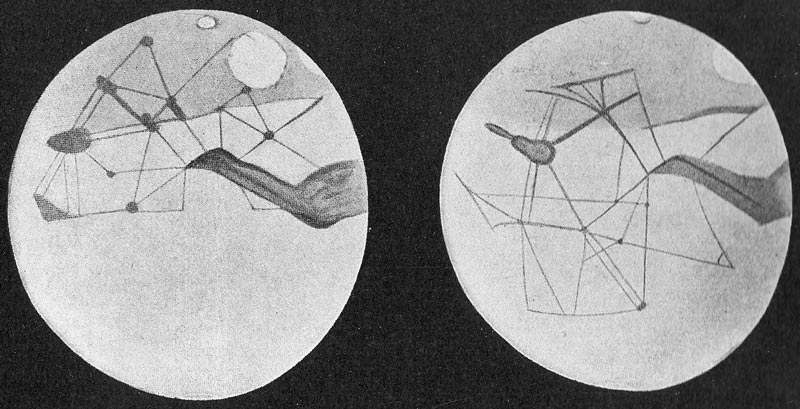

Public works on Mars

Peering through his telescope at Mars, American astronomer Percival Lowell was certain he spotted signs of intelligent life.

“That Mars is inhabited by beings of some sort or other we may consider as certain as it is uncertain what those beings may be,” as he famously wrote in 1906.

Lowell interpreted the strange patterns seen on the surface as a complex network of canals, which intelligent Martians used to irrigate their crops. Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli had reached a similar conclusion 30 years earlier. A bold interpretation, but Lowell, Schiaparelli, and others were fooled by an apparent optical illusion (or wishful thinking), as the dark markings on Mars were forged by natural geological processes.

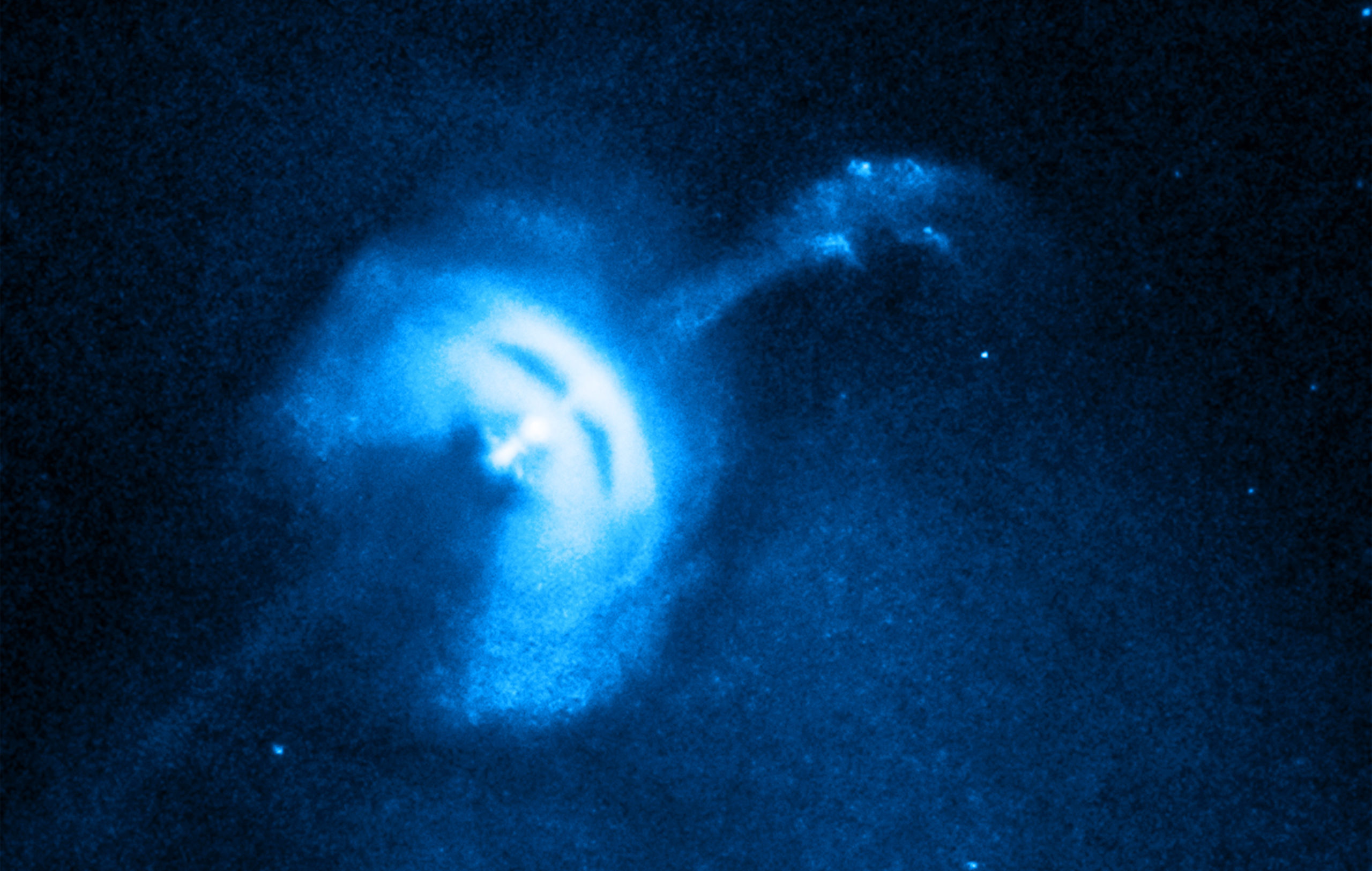

Little green men and their freaky beacons

When Nobel Prize-winning astronomer Jocelyn Bell Burnell discovered a pulsar in 1967, she didn’t quite know what to make of the object’s eerie rhythm. Here’s how she described the moment in her 1977 essay, “Little Green Men, White Dwarfs or Pulsars?”:

We did not really believe that we had picked up signals from another civilisation, but obviously the idea had crossed our minds and we had no proof that it was an entirely natural radio emission. It is an interesting problem — if one thinks one may have detected life elsewhere in the universe how does one announce the results responsibly? Who does one tell first? We did not solve the problem that afternoon, and I went home that evening very cross [as] here was I trying to get a Ph.D. out of a new technique, and some silly lot of little green men had to choose my aerial and my frequency to communicate with us.

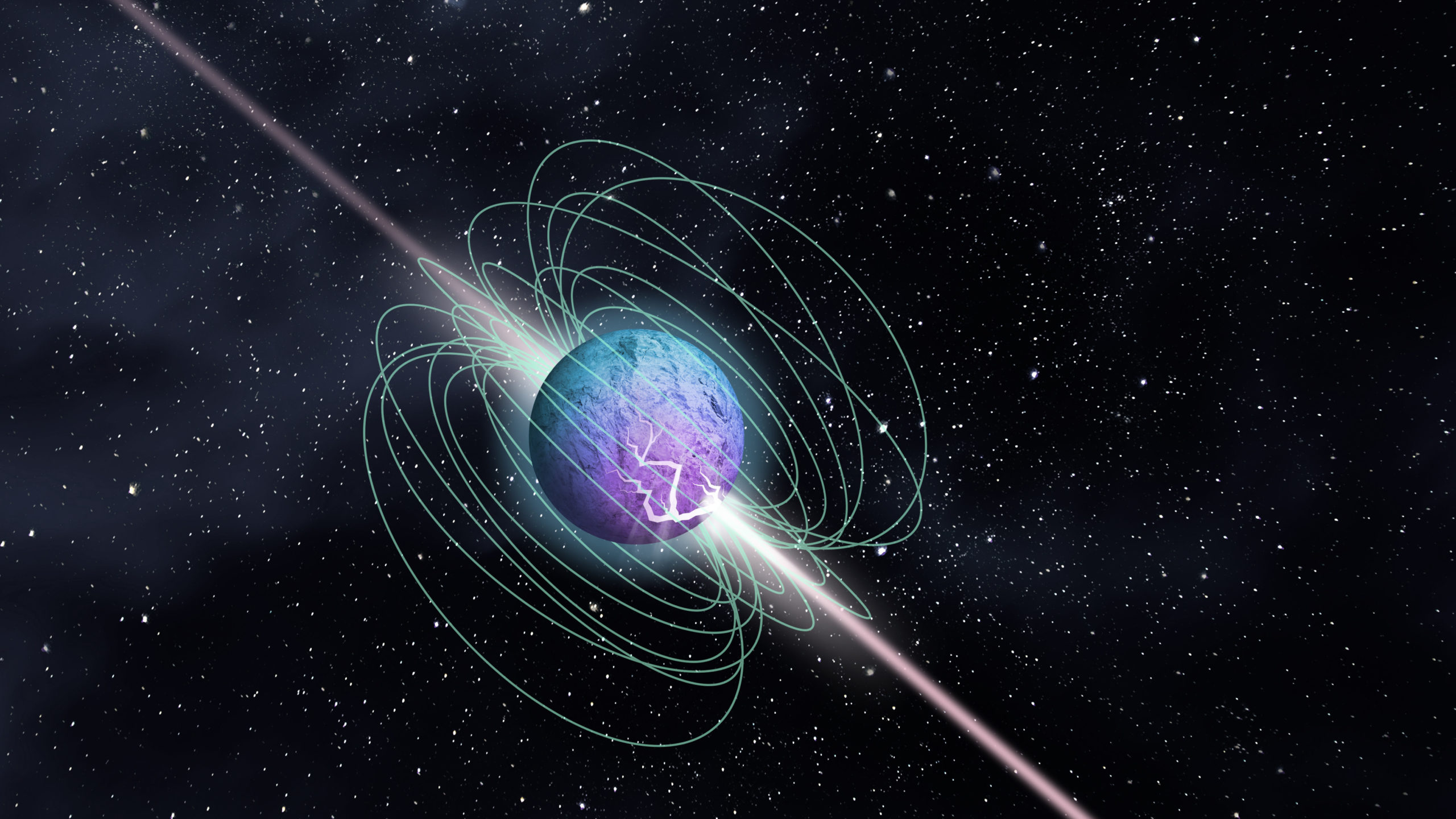

Funnily enough, Burnell and her team named the pulsar LGM-1, which stands for “little green men.” Pulsars are not celestial lighthouses built by communicative aliens, but rather periodic flashes of electromagnetic radiation produced by magnetic, rotating neutron stars.

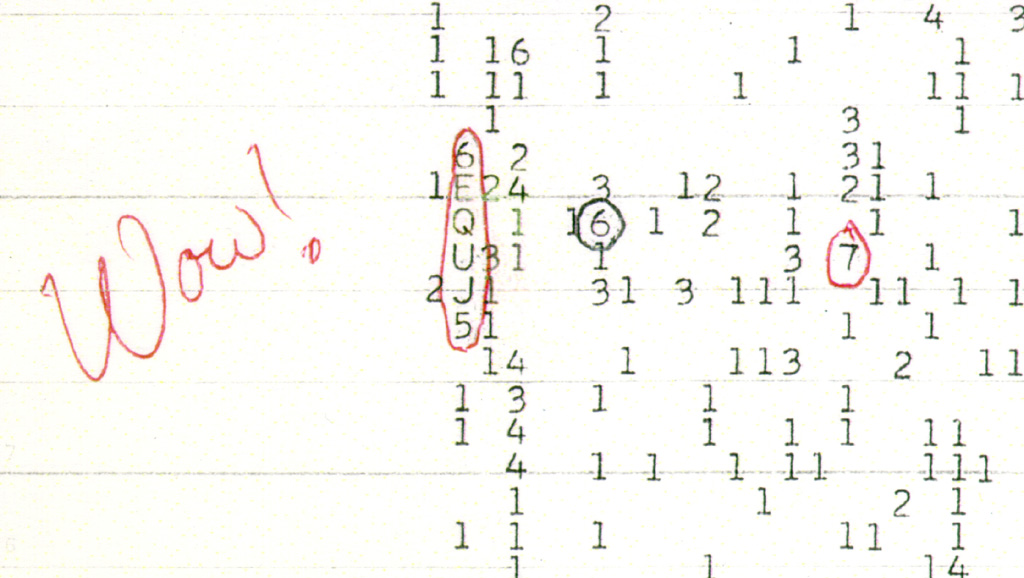

The signal that made scientists say WOW!

On August 15, 1977, astronomer Jerry Ehman detected a strange signal while working on a SETI project at Ohio State University’s Big Ear radio telescope. The 72-second sequence featured an unusual intensity, prompting Ehman to circle the letter code 6EQUJ5 in a printout and write “WOW!” in the margins. This code, which describes the intensity variation of the narrow radio signal, appeared to come from a globular cluster in the constellation Sagittarius. The source of the signal was never determined, leading to speculation that it came from aliens. Research from 2016 suggested the signal was produced not by aliens, but a hydrogen cloud caused by comets.

The SETI signal that wasn’t

During the summer of 1997, scientists with the SETI Institute detected an exceptionally narrow radio signal from space that bore the hallmarks of an alien transmission.

The signal, collected by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s 42.67 m antenna, was “millions of times more spectrally compact than a TV broadcast,” according to Seth Shostak, a team member at the time and the current senior astronomer at the SETI Institute. The scientists were super excited, because they confirmed the signal as coming from space (and not from a local source). “In years of trying, we had found no other signal that had been so promising,” he wrote in a 2016 article for Air & Space. “Could this be the real deal?”

Disappointingly, it turned out to be a telemetry signal from the SOHO solar research satellite operated by NASA and ESA.

Peculiar radio bursts from deep space

Since 2007, astronomers have detected hundreds of powerful, millisecond-long pulses known as Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). Until very recently, all of these pulses originated from outside our galaxy, making it exceptionally difficult for astronomers to pinpoint a source. Various natural phenomena were ascribed, along with the inevitable “it’s aliens” explanation. The stunning recent detection of an FRB inside our Milky Way galaxy suggests magnetars — highly magnetic neutron stars — are responsible for these signals, or at least some of them.

Peculiar radio bursts from the cafeteria

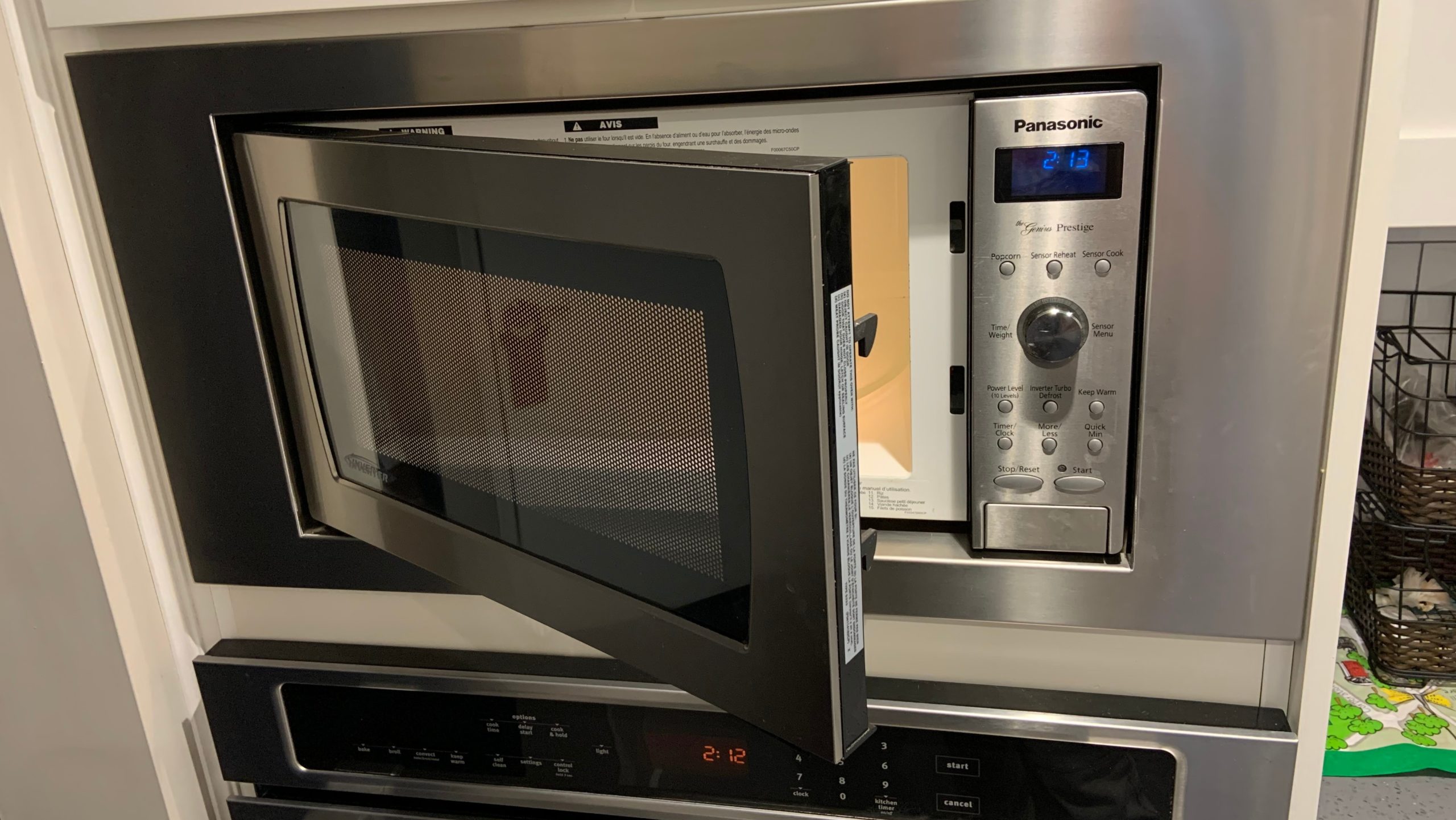

In what is one of my all-time favourite Gizmodo headlines, our former science reporter Maddie Stone wrote: “Mysterious Radio Signals Came From Microwave Oven, Not Outer Space.” Oof.

For years, astronomers at the Parkes Observatory in Australia had been flummoxed by a series of quick radio pulses that appeared to originate from deep space. At the same time, these pulses, dubbed “perytons,” seemed to come from somewhere nearby. As subsequent tests revealed, “a peryton can be generated at 1.4 GHz when a microwave oven door is opened prematurely and the telescope is at an appropriate relative angle,” according to research led by astronomer Emily Petroff from the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy.

The time 234 stars tried to get our attention

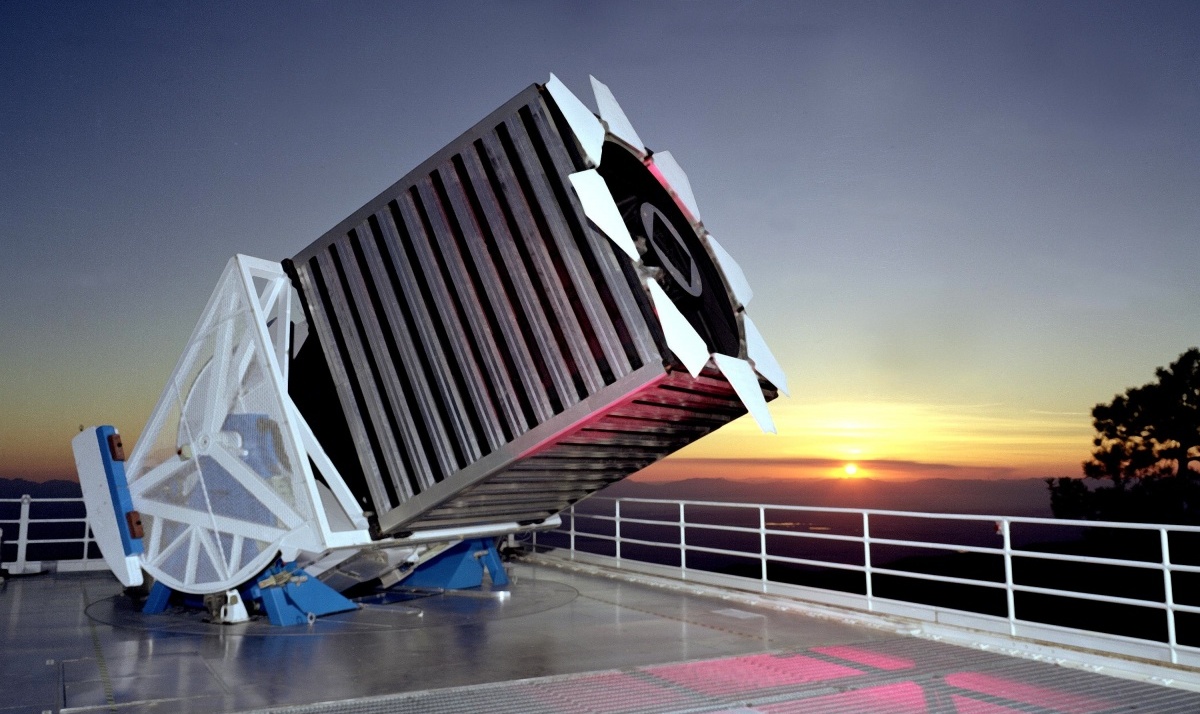

In 2016, astronomer Ermanno Borra from Laval University in Quebec, along with graduate student Eric Trottier, were exploring the possibility that advanced aliens might want to contact us with powerful directed lasers. To that end, the duo searched through 2.5 million stars recorded by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey in hopes of finding distinct periodic spectral signatures consistent with such a technological feat. Of these, Borra and Trottier found 234 candidates, all emanating from very Sun-like stars. After ruling out several possibilities, the authors settled on two possible outcomes: Either these signals are an artefact from the Sloan instrument, or, ahem, aliens.

A follow-up letter written by researchers from the Breakthrough Listen initiative said the “one in 10,000 objects with unusual spectra seen by Borra and Trottier are certainly worthy of additional study,” but “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. It is too early to unequivocally attribute these purported signals to the activities of extraterrestrial civilisations.”

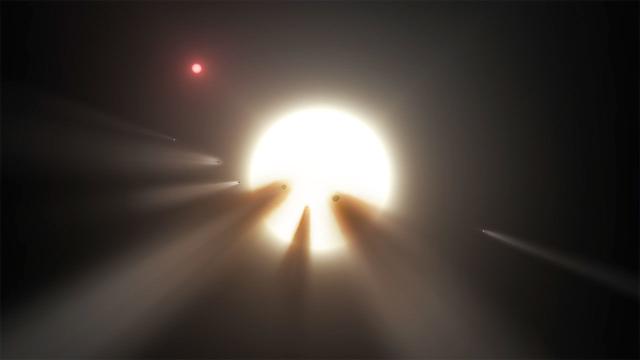

Boyajian’s Star and the supposed ‘alien megastructure’

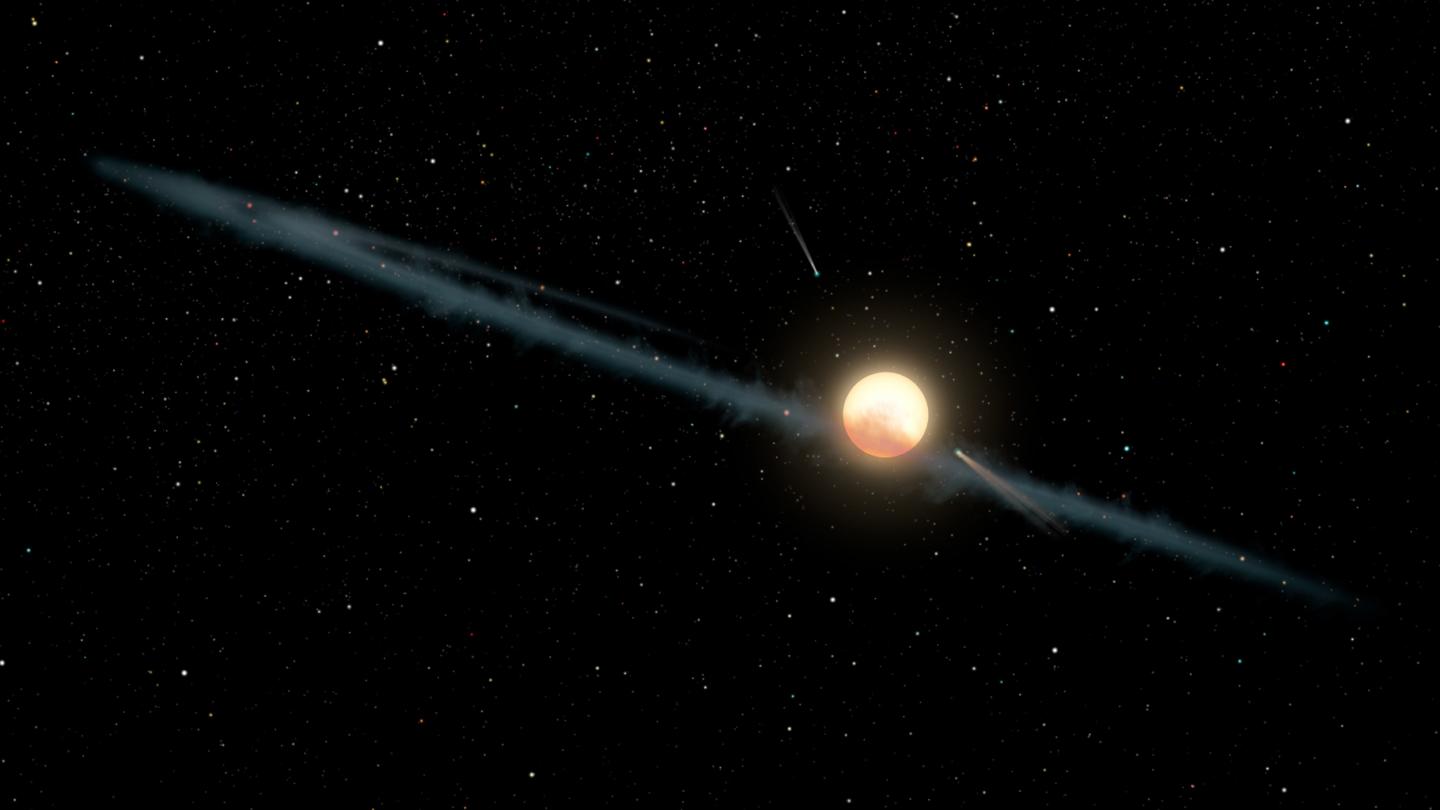

Astronomers have known about KIC 8462852 for nearly 130 years, but this star, informally known as Boyajian’s Star, has been acting strangely of late. In 2015, Louisiana State University astrophysicist Tabetha Boyajian began to notice some intermittent dimming, sometimes by as much as 22%. These changes in luminosity lasted for a few days or weeks, and no patterns to the dimming could be detected.

News of Boyajian’s Star prompted all sorts of explanations, from a swarm of comets and an irregular band of dust through to a newly destroyed planet and a distorted star. Penn State astronomer Jason Wright shook the science community by proposing the presence of an alien megastructure, like a Dyson sphere. Research from 2019 suggests a disintegrating moon is the most likely cause of the strange dimming.

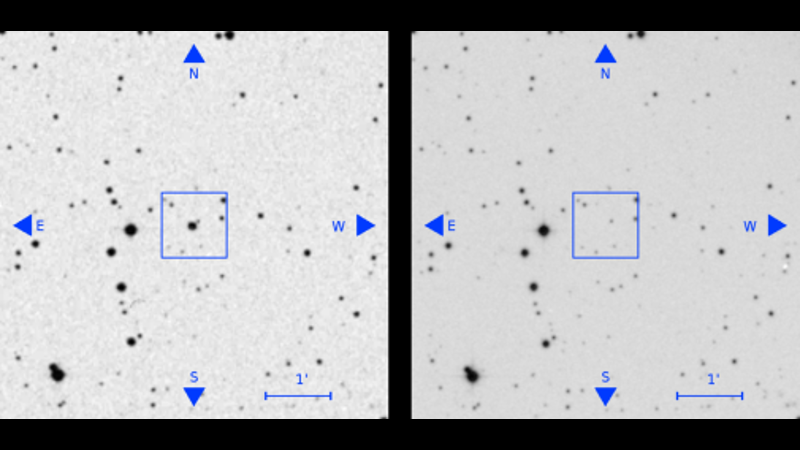

Vanishing stars

Research from last year identified around 100 vanishing stars, which, as the name suggests, are, uh, vanishing stars. More technically known as red transients, these stars initially appear as dim red dots that get progressively brighter and then disappear from view, in an unexplained process that lasts less than an hour.

“Unless a star collapses directly into a black hole, there is no known physical process by which it could physically vanish,” wrote the researchers, led by Beatriz Villarroel from Stockholm University, in their paper. “If such examples exist this makes it interesting for searches for new exotic phenomena or even signs of technologically advanced civilisations.”

These “exotic phenomena” could include failed supernovae or massive solar flares emanating from red dwarfs, but we don’t actually know. Vanishing stars remain a question in need of an answer, affording us the opportunity to blame aliens — at least for now.

Stay open-minded

It may seem like I’m poking fun, but I have all the time in the world for the types of speculations described in this piece. In virtually every case, the scientists listed as many natural phenomena — both known and speculative — as possible to explain the inexplicable, prior to invoking alien involvement.

Scientists should be allowed to posit these types of speculations, and possibilities must remain possibilities until scientists can rule them out. Because one day, that strange thing we detect might actually be aliens.