Behind that putrefying flesh, there’s a lot of hidden depth to the zombie. As humanities scholar Jeffery Cohen puts it in his book Monster Theory: Reading Culture, “monsters provide a key to understanding the culture that spawned them.” In 1918, with the Spanish Flu ravaging the U.S., we turned our fears into zombies.

Many mistakenly date zombies’ shuffling, limping entry into popular culture with George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968. The whole need-to-eat-human-flesh to survive thing is definitely present in the film, but the story only ever refers to its flesh eating monsters — born of an infectious disease — as “ghouls.” In one of the most iconic zombie films ever made, the word “zombie” is not once uttered.

The Hollywood debut of the flesh-eaters actually dates back to Edward Halperin’s 1932 White Zombie. The film is based on William Seabrook’s 1929 travelogue, The Magic Island, where he recounts his travels in Haiti. Seabrook’s retelling of his travels is saturated in racism, and zombies have never quite shaken their racist origins.

In his book, Seabrook describes Haiti’s zombie as “a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life.” But he didn’t just make the concept up.

The zombie was a real, indigenous piece of Haitian folklore. Haiti’s zombies are a haunting echo to the brutal slave plantations that dominated French Haiti until the 1804 slave-led revolution on the island. As Amy Wilentz has written, during the brutal French colonisation of Haiti, the zombie embodied former slaves’ fears of becoming re-enslaved even after death. When you died, according to Haitian belief, you returned to lan guinee, “Africa,” and freedom. But, in Haitian folklore, what made zombies so terrifying was that they are denied death’s freedom and barred from lan guinee.

Seabrook twisted Haitian zombie lore with his brand of racist rhetoric, writing that the people with the powers to reanimate a zombie become the zombie’s “master” and “make of it a servant or slave, occasionally for the commission of some crime, more often simply as a drudge around…the farm, setting it dull heavy tasks, and beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens.”

While some more recent films like 1988’s The Serpent and the Rainbow draw on the Haitian origins of the zombies, most of our zombie films draw on another horrific event — the 1918 flu pandemic.

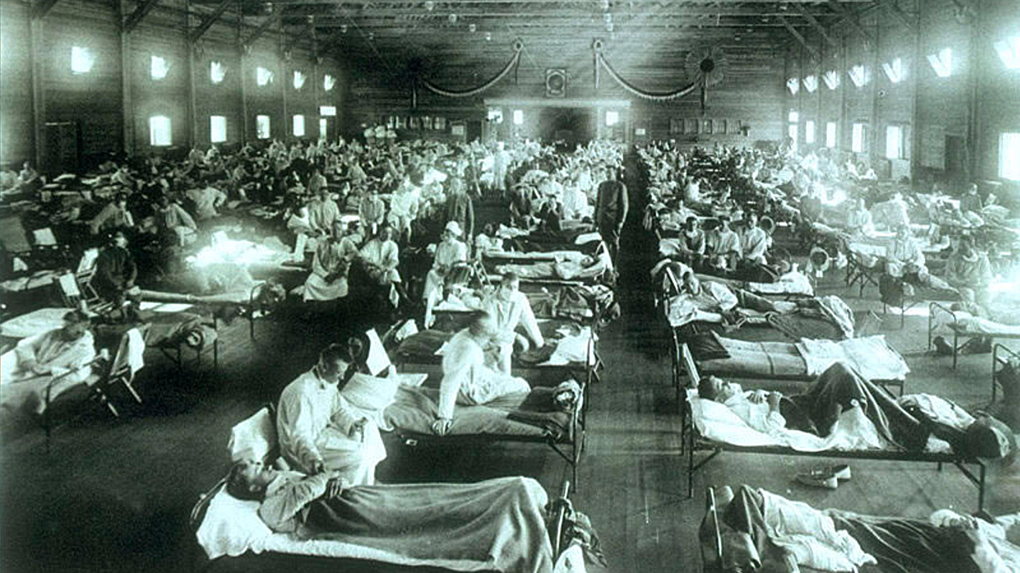

The 1918 flu killed 50-100 million people and infected 500 million people — about a third of the world’s population. In the U.S. alone, more people died of the 1918 flu than all 20th and 21st-century wars combined. Victims, many of them young adults, could die within hours of being brought to hospitals.

The 1918 flu outbreak had something of a “body problem,” University of Richmond literature professor Elizabeth Outka explained. Funerals were suspended. Towns ran out of coffins. The dead were left on footpaths and porches, and mass graves were dug around the country to dispose of the bodies. In Philadelphia alone, the demand for coffins was so intense they arrived in the city under armoured guard.

As Outka frames it, “There was a widespread fear that bodies were insecurely buried” during the pandemic. There was no sense of closure, no funerals, and instead the dead were interred quickly and haphazardly. The fear and anxieties these hasty burials created “made for a fertile atmosphere [for zombies],” according to Outka. There was a fear that the dead weren’t properly put to rest and could come back to prey on the living because of it.

Outka connects this fear of “insecure burials” to World War I, which was ending just as the pandemic was beginning. (The 1918 pandemic began on a WWI army base in fact — central Kansas’s Camp Funston.) The bodies of many WWI soldiers were never recovered. The bodies that were found were often unidentifiable, and shellfire destroyed many of the haphazard graves dug near the fighting.

The 1918 flu also had some terrifying, zombie-like symptoms. Beyond just high fever and body aches, victims’ faces and extremities would take on a sickly bluish colour. Just breathing was difficult for many. As one sufferer wrote, “I was some specimen of misery [and] couldn’t breathe without an excruciating cough.” In severe cases, victims would cough up foamy blood and bleed from their nose, ears, and even eyes.

Perhaps most terrifying of all though was the sudden delirium that came over victims in their final days and hours. As one nurse put it, “if we couldn’t get [patients’] temperatures down, they dropped suddenly — below subnormal — and they started delirium. And once they got very delirious, we just couldn’t save them… The noise of the delirium at night was terrific.” Another witness remembers how his friend “went raving mad” and started “running around the room with a knife” before dying the next morning.

Even those who recovered from the illness often suffered severe psychological effects. As Outka explains it, “The flu could produce a… sense of living death in survivors. [Victims] were so spent and so worn out that [they] were just walking around half alive.”

The fears around insecure burials and the flu’s zombie-like symptoms creates a link to zombies’s entry into American culture, an entry recorded in horror writer H. P. Lovecraft’s grotesque stories. (Lovecraft was also a known racist, as Lovecraft Country brought to the forefront.) A new 2015 anthology, The Zombie Stories of H. P. Lovecraft, collects all of what Outka calls Lovecraft’s “proto-zombies” tales.

Most of Lovecraft’s zombie-like monsters are doctors with close ties to the pandemic. Outka explains, “there was a great deal of gratitude towards doctors and nurses who had risked their lives during the pandemic, but there was also some resentment in that the doctors and nurses could really do little but help their patients be more comfortable. And, Lovecraft captures a sense of anger at that.”

Lovecraft’s Herbert West: Reanimator, for instance, takes place in the midst of a typhoid epidemic. The dead are piling up. Graves are overflowing. And that’s when the evil Herbert West reanimates the dead body of a rival doctor into “the plague-daemon” in the name of scientific inquiry. The story’s narrator describes how, of the fourteen people it murdered, the monster “had not left behind quite all that it had attacked, for sometimes it had been hungry.” Yikes!

Lovecraft’s stories also speak to fears around the haphazard burials during the influenza. In Lovecraft’s In the Vault, an undead corpse takes a bite out of a vindictive undertaker who hadn’t properly buried the body.

As zombie scholar Jasie Stokes emphasises, Lovecraft’s monsters in these stories mark a departure from the Haitian zombie. Lovecraft’s undead are autonomous. They eat and kill not because some master-figure is forcing them to, as in the Haitian legend. They eat and kill because that’s just kind of what they do. Unlike the influenza though, Lovecraft’s proto-zombies can be killed.

We create monsters because monsters are killable. We all know silver bullets can kill a werewolf and crosses burn a vampire. In just about every horror movie ever made, even the most terrifying monsters have an Achilles’ heel. In 1984’s Nightmare on Elm Street, it’s lucid dreaming. In 2014’s The Babadook, it’s regular meals of worms and maggots. In Zombieland, it’s just a good ol’ shotgun. There’s always some way of killing or trapping or exorcising the monster.

Fear is a far more difficult thing to kill than a zombie. We can calm our fears, but there’s no way to kill fear entirely. That’s why we need our monsters, to make the intangible physical. In this way, horror films can calm our fears even when they terrify us.

Sarah Durn is a freelance writer, actor, and medievalist based in New Orleans, Louisiana. She is the author of The Beginner’s Guide to Alchemy.